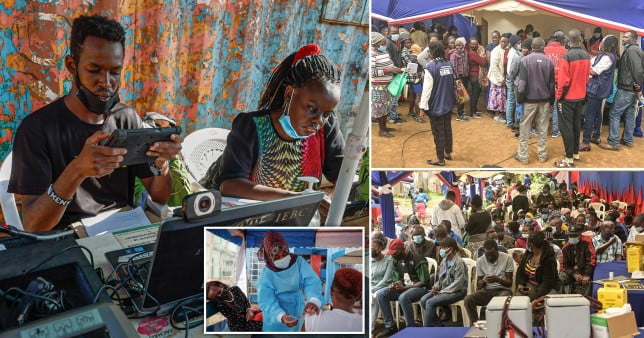

African nations were amongst the last to get Covid-19 vaccines after most of the world’s supply went to countries abundant enough to work out straight with makers.

By the time the UK was presenting its booster program last September, just 1.6% of Kenya’s population was totally immunized, with doctors turning people away because they had no jabs.

Developing countries slowly started getting enough doses to begin their own inoculation drives, but WHO figures estimate only 7.5% of Africa’s 1.2 billion population had been vaccinated.

Although this number will have risen over the weeks since, it will almost certainly remain far below the WHO’s December target of 40%.

More than a third of doses that arrived on the continent have not yet been used, according to the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI).

Metro.co.uk spoke to two experts to find out why.

Funding healthcare workers

One of the biggest barriers to getting jabs into arms is paying for the healthcare workers to inject people.

This is particularly difficult in developing countries where many populations are dispersed across rural areas – where there are very few, if any, nurses and doctors qualified to give shots.

So healthcare workers based in cities often have to travel around the country to jab people who would otherwise have to make the long, expensive journey themselves.

This is expensive as it adds accommodation, travel, food and more to the cost of paying healthcare workers’ salaries.

Adam Bradshaw, the TBI’s senior coronavirus adviser, said: ‘A lot of vaccine workers will travel 10 hours, pay for it with their own money – for their fuel, accommodation, food and the rest. But that’s not a sustainable model.

‘You wouldn’t expect that in a high-income country and we shouldn’t expect it in a low-income country either.’

Finding the money to fix this problem is difficult, as poorer nations have to look for it in the funds they are already spending on other health and development costs.

Unplanned donations and expiry dates

The majority of vaccines on the continent have arrived through donations – directly from countries or through the WHO’s Covax scheme, according to TBI policy associate Liya Temeselew.

But these jabs seemed to be getting donated when richer countries were sure they did not need them, meaning they were often nearing their expiry dates by the time they got to Africa.

It means governments have to plan immunity schemes ‘with very little information about how many vaccines are going to arrive when’.

Mr Bradshaw, who previously advised New Zealand’s government on vaccine policy, said: ‘Even high-income countries, if they received vaccines with a three-week shelf life, they wouldn’t be able to plan a rollout campaign. It would be unrealistic to expect that of any country.’

This is expected to change soon as Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) has said it will not accept any vaccines with less than a three-month shelf life.

The director of Africa CDC, Dr John Nkengasong, says countries should aim to donate jabs which are around six months before their expiry dates.

Vaccine hesitancy

People in developing nations have been subject to the same misinformation and political controversy that has caused vaccine hesitancy in western countries.

But the ‘unfair’ way jabs have been distributed globally has also impacted how Africans see the shots offered to them, according to both Mr Bradshaw and Ms Temeselew, who is helping with Ethiopia’s vaccine programme.

They said: ‘If you see in the news that the vaccines coming to your country are nearing their expiry date, the perception of this isn’t particularly great.’

On top of this, the unreliability of jab availability ‘undermines the credibility and confidence in vaccines’.

Solutions

Helping African nations pay their health care employees and produce vaccines on the continent are 2 of the quickest methods to repair the issue.

Mr Bradshaw worried the next 6 months are a ‘crucial window of opportunity to up vaccinations in Africa’ due to the fact that it’s in between the current Omicron wave and when the next wave is forecasted.

But he thinks the world requires a more ‘long-term, sustainable solution’ due to the fact that‘this is important for the whole of the global community’

.

King’s College medical historian Caitjan Gainty informedMetro co.uk: ‘The immediate problems are maybe logistical problems but the underlying problems are always these much larger, deeper, historical problems about the way in which the world is divided in terms of power and wealth and all those kinds of things.’

Get in touch with our news group by emailing us at webnews@metro.co.uk.

For more stories like this, examine our news page

Get your need-to-know.

most current news, feel-good stories, analysis and more