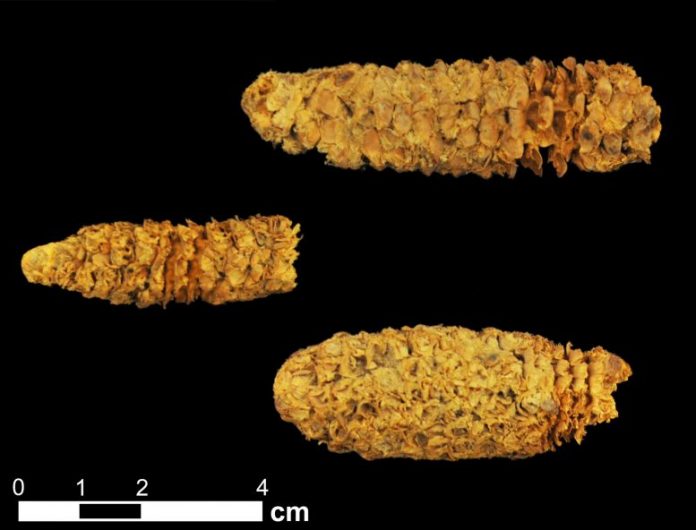

Three approximately 2,000-year-old corn cobs from the El Gigante rock shelter website in Honduras. These corn cobs were genetically evaluated by a global group of researchers. In the Dec. 14 problem of the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Logan Kistler, manager of archaeogenomics and archaeobotany at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and a global group of partners report the totally sequenced genomes of 3 approximately 2,000-year-old cobs from the El Gigante rock shelter in Honduras. Analysis of the 3 genomes exposes that these millennia-old ranges of Central American corn had South American origins and includes a brand-new chapter in an emerging complex story of corn’s domestication history. Taken together with current research studies about the domestication of corn in this area, these newest findings recommend that something special might have taken place in the domestication of corn about 4,000 years back in Central America, which an injection of hereditary variety from South America might have had something to do with it. Credit: Thomas Harper

Three 2,000-year-old cobs in Honduras reveal that individuals brought corn ranges back to Mesoamerica, perhaps triggering performance and forming civilization.

Some 9,000 years back, corn as it is understood today did not exist. Ancient individuals in southwestern Mexico experienced a wild yard called teosinte that used ears smaller sized than a pinky finger with simply a handful of stony kernels. But by stroke of genius or need, these Indigenous farmers saw possible in the grain, including it to their diet plans and putting it on a course to end up being a domesticated crop that now feeds billions.

Despite how crucial corn, or maize, is to contemporary life, holes stay in the understanding of its journey through area and time. Now, a group co-led by Smithsonian scientists have actually utilized ancient DNA to complete a few of those spaces.

A brand-new research study, which exposes information of corn’s 9,000-year history, is a prime example of the manner ins which fundamental research study into ancient DNA can yield insights into human history that would otherwise be unattainable, stated co-lead author Logan Kistler, manager of archaeogenomics and archaeobotany at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

“Domestication — the evolution of wild plants over thousands of years into the crops that feed us today — is arguably the most significant process in human history, and maize is one of the most important crops currently grown on the planet,” Kistler stated. “Understanding more about the evolutionary and cultural context of domestication can give us valuable information about this food we rely on so completely and its role in shaping civilization as we know it.”

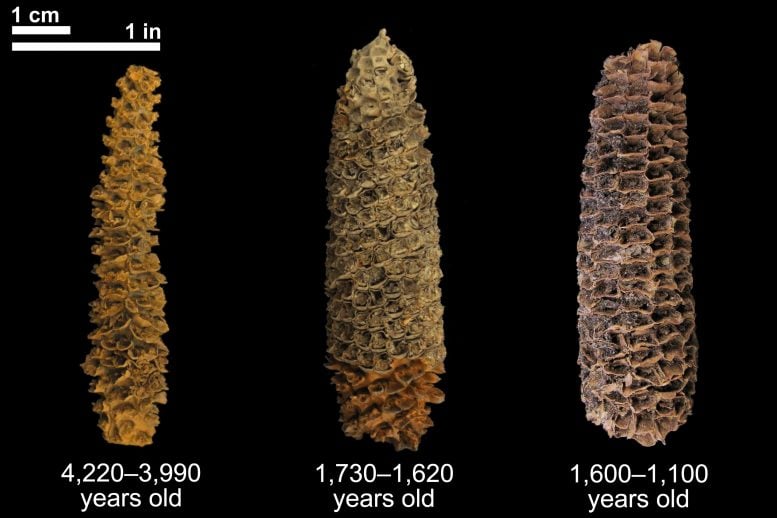

An variety of corn cobs of differing ages discovered at the El Gigante rock shelter website in Honduras. Credit: Thomas Harper

In the December 14, 2020, problem of the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Kistler and a global group of partners report the totally sequenced genomes of 3 approximately 2,000-year-old cobs from the El Gigante rock shelter in Honduras. Analysis of the 3 genomes exposes that these millennia-old ranges of Central American corn had South American origins and includes a brand-new chapter in an emerging complex story of corn’s domestication history.

“We show that humans were carrying maize from South America back towards the domestication center in Mexico,” Kistler stated. “This would have provided an infusion of genetic diversity that may have added resilience or increased productivity. It also underscores that the process of domestication and crop improvement doesn’t just travel in a straight line.”

Humans initially began selectively reproducing corn’s wild forefather teosinte around 9,000 years back in Mexico, however partly domesticated ranges of the crop did not reach the rest of Central and South America for another 1,500 and 2,000 years, respectively.

For several years, traditional thinking amongst scholars had actually been that corn was very first totally domesticated in Mexico and after that spread out in other places. However, after 5,000-year-old cobs discovered in Mexico ended up to just be partly domesticated, scholars started to reevaluate whether this believing caught the complete story of corn’s domestication.

Then, in a landmark 2018 research study led by Kistler, researchers utilized ancient DNA to reveal that while teosinte’s initial steps towards domestication happened in Mexico, the procedure had actually not yet been finished when individuals very first started bring it south to Central and South America. In each of these 3 areas, the procedure of domestication and crop enhancement relocated parallel however at various speeds.

An variety of corn cobs of differing ages discovered at the El Gigante rock shelter website in Honduras. After researchers initially found the residues of a completely domesticated and extremely efficient range of 4,300-year-old corn at the El Gigante rock shelter, a group browsed the historical strata surrounding the website for other cobs, kernels or anything else that may yield hereditary product. They likewise began pursuing sequencing a few of the website’s 4,300-year-old corn samples–the earliest traces of the crop at El Gigante. Over 2 years, the group tried to series 30 samples, however just 3 were of appropriate quality to series a complete genome. The 3 practical samples all originated from the more current layer of the rock shelter’s profession–carbon dated in between 2,300 and 1,900 years back–revealing hereditary overlap in between the 3 samples from the Honduran rock shelter and corn ranges from South America. In the Dec. 14 problem of the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Logan Kistler, manager of archaeogenomics and archaeobotany at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and a global group of partners report the totally sequenced genomes of 3 approximately 2,000-year-old cobs from the El Gigante rock shelter in Honduras. Analysis of the 3 genomes exposes that these millennia-old ranges of Central American corn had South American origins and includes a brand-new chapter in an emerging complex story of corn’s domestication history. Credit: Thomas Harper

In an earlier effort to focus on the information of this richer and more complicated domestication story, a group of researchers consisting of Kistler discovered that 4,300-year-old corn residues from the Central American El Gigante rock shelter website had actually originated from a completely domesticated and extremely efficient range.

Surprised to discover totally domesticated corn at El Gigante existing side-by-side in an area not far from where partly domesticated corn had actually been found in Mexico, Kistler and job co-lead Douglas Kennett, an anthropologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, collaborated to genetically identify where the El Gigante corn stemmed.

“El Gigante rock shelter is remarkable because it contains well-preserved plant remains spanning the last 11,000 years,” Kennett stated. “Over 10,000 maize remains, from whole cobs to fragmentary stalks and leaves, have been identified. Many of these remains date late in time, but through an extensive radiocarbon study, we were able to identify some remains dating to as early as 4,300 years ago.”

They browsed the historical strata surrounding the El Gigante rock shelter for cobs, kernels or anything else that may yield hereditary product, and the group began pursuing sequencing a few of the website’s 4,300-year-old corn samples — the earliest traces of the crop at El Gigante.

Over 2 years, the group tried to series 30 samples, however just 3 were of appropriate quality to series a complete genome. The 3 practical samples all originated from the more current layer of the rock shelter’s profession — carbon dated in between 2,300 and 1,900 years back.

With the 3 sequenced genomes of corn from El Gigante, the scientists evaluated them versus a panel of 121 released genomes of different corn ranges, consisting of 12 originated from ancient corn cobs and seeds. The contrast exposed bits of hereditary overlap in between the 3 samples from the Honduran rock shelter and corn ranges from South America.

“The genetic link to South America was subtle but consistent,” Kistler stated. “We repeated the analysis many times using different methods and sample compositions but kept getting the same result.”

Kistler, Kennett and their co-authors at working together organizations, consisting of Texas A&M University, Pennsylvania State University along with the Francis Crick Institute and the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom, assume that the reintroduction of these South American ranges to Central America might have jump-started the advancement of more efficient hybrid ranges in the area.

Though the outcomes just cover the El Gigante corn samples dated to around 2,000 years back, Kistler stated the shape and structure of the cobs from the approximately 4,000-year-old layer recommends they were almost as efficient as those he and his co-authors had the ability to series. To Kistler, this implies the smash hit crop enhancement most likely happened prior to instead of throughout the stepping in 2,000 years approximately separating these historical layers at El Gigante. The group even more assumes that it was the intro of the South American ranges of corn and their genes, likely a minimum of 4,300 years back, which might have increased the performance of the area’s corn and the occurrence of corn in the diet plan of individuals who resided in the wider area, as found in a current research study led by Kennett.

“We are starting to see a confluence of data from multiple studies in Central America indicating that maize was becoming a more productive staple crop of increasing dietary importance between 4,700 and 4,000 years ago,” Kennett stated.

Taken together with Kennett’s current research study, these newest findings recommend that something special might have taken place in the domestication of corn about 4,000 years back in Central America, which an injection of hereditary variety from South America might have had something to do with it. This proposed timing likewise lines up with the look of the very first settled farming neighborhoods in Mesoamerica that eventually triggered excellent civilizations in the Americas, the Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan and the Aztec, though Kistler quickened to mention this concept is still relegated to speculation.

“We can’t wait to dig into the details of what exactly happened around the 4,000-year mark,” Kistler stated. “There are so many archaeological samples of maize which haven’t been analyzed genetically. If we started testing more of these samples, we could start to answer these lingering questions about how important this reintroduction of South American varieties was.”

Reference: “Archaeological Central American maize genomes suggest ancient gene flow from South America” by Logan Kistler, Heather B. Thakar, Amber M. VanDerwarker, Alejandra Domic, Anders Bergström, Richard J. George, Thomas K. Harper, Robin G. Allaby, Kenneth Hirth and Douglas J. Kennett, 14 December 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2015560117

Funding and assistance for this research study were offered by the Smithsonian, National Science Foundation, Pennsylvania State University and the Francis Crick Institute.