A brand-new ASU research study reveals that the external plastic finish around laundry and meal pods requires particular conditions to biodegrade. These conditions are not fulfilled in traditional water treatment plants in the U.S. This permits lots of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) to leave into the environment each year.

Outer pod product packaging requires a particular environment to entirely biodegrade.

The simpleness of getting a laundry or dishwashing machine pod and tossing it into the maker has actually made them a popular option for numerous customers for almost a years.

Detergent and other active ingredients are packaged inside a dissolvable plastic finish called polyvinyl alcohol, or PVA. This artificial polymer, utilized given that the early 1930s, is water-soluble and disintegrate throughout the wash cycle, launching the cleaning agent.

Many business declare PVA is naturally degradable. While it can be totally naturally degradable, particular conditions are required for it to entirely biodegrade. These conditions are frequently unmet. Also, as it liquifies upon contact with water, it can launch ethylene, which is a fossil-fuel-based chemical.

This got 2 Arizona State University scientists questioning what occurs to PVA when it reaches wastewater treatment plants.

“There are very strict conditions needed for PVA to biodegrade, and this is not met within conventional water treatment in the U.S.,” stated Charlie Rolsky, co-first author of a brand-new research study released in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. “We can take a look at the literature and evaluate just how much PVA is breaking down, and in what area of the wastewater treatment plant. We can integrate that with just how much wastewater is created in the U.S. and the number of of these laundry and meal pods are utilized in the U.S. each year.

“When we put these pieces together, we can project how much PVA goes untreated and is released into the environment,” stated Rolsky, a postdoctoral scientist with the ASU Biodesign Center for Sustainable Macromolecular Material and Manufacturing.

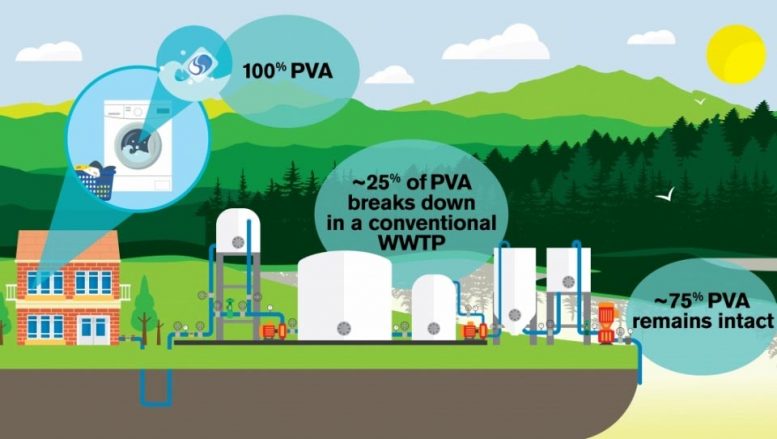

The research study, released in June 2021, reveals that as much as 75% of PVA goes neglected in the U.S. each year. That totals up to about 8,000 lots of the plastic product being launched each year onto land and into waterways throughout the nation.

A brand-new Arizona State University research study released in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health reveals that as much as 75% of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) goes neglected in the U.S. each year. That totals up to about 8,000 lots of the artificial polymer being launched each year onto land and into waterways throughout the nation. Credit: Shireen Dooling

According to co-first author Varun Kelkar, a PhD prospect and scientist with the Biodesign Center for Environmental Health Engineering, along with a volunteer with Plastic Oceans International, numerous business employ outdoors companies to produce particular biological environments appropriate for PVA to break down. By doing so, the business utilizing PVA in its items can declare it’s naturally degradable. But, he stated, wastewater treatments plants in the U.S. are normally not developed to produce optimum conditions for this particular polymer. Instead, they are developed to deal with human waste and other biological matter.

“According to our model, most of the PVA just passes through the treatment plant,” Kelkar stated. “And then it depends. It might completely biodegrade if the environmental conditions are met. And if they’re not met, say in a cool area where the bacterial activity is relatively low, it’s unknown what happens to this large amount of polyvinyl alcohol.”

Both scientists state it’s time to take a more detailed take a look at what it in fact implies for a product to be naturally degradable, and whether business must be enabled to declare their items are naturally degradable if they just are so under particular conditions.

“A general understanding of biodegradable is that it’s something that can completely vanish. You throw it into the environment, and like food, it should go away without any side effects and be biologically available to microorganisms for fuel,” Kelkar stated. “Yet, we know this is not the case with PVA.”

PVA is utilized in a wide range of items — it’s frequently discovered in fabrics, paper, adhesives, and paints, and it likewise has medical, commercial, and industrial applications. While Rolsky and Kelkar state they do not mean to damn PVA as a useful product, they do have issues about what it might be doing, undetected, to the environment.

“A lot of companies are claiming that PVA is biodegradable. It’s not fully degrading,” Rolsky stated. “And there really isn’t any literature or research on PVA as a pollutant. We know it’s out there, but we don’t know whether it’s causing harm. We know it can sequester heavy metals and leach into groundwater. It can also alter gas exchanges, which can affect aquatic ecosystems, and we know that ethylene, a byproduct of PVA, is a hormone that plants utilize. It’s important that we study this further.”

Reference: “Degradation of Polyvinyl Alcohol in US Wastewater Treatment Plants and Subsequent Nationwide Emission Estimate” by Charles Rolsky and Varun Kelkar, 3 June 2021, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18116027

This research study was supported in part by Plastic Oceans International and Blueland.