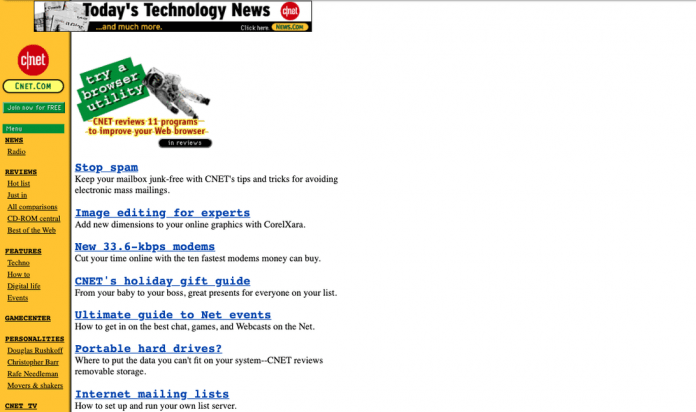

The style of the web has actually altered because this early CNET homepage, however we’re still battling a war on spam.

Screenshot by Kent German/CNET

This story becomes part of CNET at 25, commemorating a quarter century of market tech and our function in informing you its story.

My web circa 1995 will constantly be 3 websites: Suck, Argon Zark and the T.W.I.N.K.I.E.S Project.

Put up by 2 Rice University trainees to record their experiments to figure out the homes of Twinkies, the T.W.I.N.K.I.E.S Project was text heavy, with tacky graphics and small pictures. Ugly, however filled with smarts, character and innocent beauty. And a quarter of a century later on, the homemade website still makes me <smile>, even if the only method to see it remains in the Internet Archive.

Suck was sort of the opposite. A disrespectful, profane and slickly packaged (for the time) handle the news of the day with the punch line “a fish, a barrel, and a smoking gun,” filled with bite-sized snarky bits that presaged the composing design of Web 2.0. It released and died with the dotcom bubble.

Yes, this is what a normal website actually appeared like in 1995, though this is from a page archived in 1999. How could you withstand a website that subjected a Twinkie to the Turing test? (Spoiler alert: Twinkies aren’t sentient.)

Chris Gouge and Todd Stadler. Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

And the Argon Zark interactive webcomic merely was Web 1995 — about it, developed particularly for it, loaded filled with links to take you to strange locations and produced with the innovative procedural graphics software application of the day from MetaTools like KPT Bryce and Kai’s Power Tools. It was jumbled and intricate and complicated and stuffed with excessive colors and gradients that merely defied printing.

It likewise represents the past’s web today: The initial pages are a collection of links to dead or forgotten websites where you might serendipitously step on a fond memories landmine. Unlike a number of its mate, however, it’s still alive and upgraded frequently.

Argon Zark was a wonderful secret trip of the time. Every among these spheres took you…someplace.

Charley ParkerCNET birthed its site in June 1995, right before the Internet Gold Rush (consequently called the “dotcom bubble” when it ended 5 years later on) formally started on Aug. 9 when Netscape’s IPO freaked out.

Many people in tech publishing didn’t actually see. (At the time, I was among them, operating at Ziff Davis’ temporary Windows Sources publication.) CNET was simply among the crowds of publications wanting to plant its flag on the Web and get a piece of the Windows 95 mindshare boom. It was the one with the strange logo design that had a pipeline in it which — unlike a number of us — had actually begun with TELEVISION and not print. And that smart TELEVISION advertisement.

Clearly CNET had more remaining power than we presumed it would.

1995: The wonder year

In the mid-1990s, the web and the internet experienced a tectonic shift, much of it concentrated in 1995. The web may have been invented in 1989, but toward the end of 1995 it went straight from toddler to moody, awkward teenager. The number of sites shot up from 23,500 to 100,000 between June 1995 and January 1996, an increase of more than 300% compared with 135% the six months prior.

Much of the growth explosion can be attributed to Microsoft’s Windows 95 release, the first truly friendly and functional version of its operating system. With the debut of Winsock (the programming interface for connecting to networks) and the bundling of Internet Explorer, which Microsoft also released in 1995, it was suddenly easy(ish) to pop on and check out the web. Apple was wandering around lost at the time. That was the tail end of the forgettable Amelio years.

Even in 1996 Yahoo was keepin’ it simple.

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

Everyone tried to find a way to impose some sort of order on the web-slash-internet, to avoid succumbing to feeling lost; that same feeling you get when shopping for a USB cable on Amazon. We generated endless lists of cool websites to see and Internet directories like Yahoo, which introduced its search feature in 1995. There were novel, but ultimately doomed, startups like Webrings, the spiritual predecessor of “see next,” and over the course of the following years more serious technologies like Backweb, the grandaddy-in-law of push notifications.

Porn was still mostly found on the internet, not yet on the web (which is really a layer on top of the internet). Links were still “hypertext links,” web development was “HTML authoring,” and we still called it “the World-Wide Web” and “the information superhighway.” GIFs and JPEGs and sound were “multimedia.” GeoCities was the place to be if you wanted to create your own site. AOL was still America Online and boasted 2.9 million subscribers who paid it to connect to the Internet.

Before the cats came

Brett Pearce/CNET

As this groundwork was being laid, the web in the first half of 1995 bore little resemblance to our experience today. Nothing popped up before, during or after you loaded a page. It was before cats took over, before you could DM, PM or IM anyone. Before push notifications, before Flash, before shopping was common and streaming was possible. Not just before Google — before AltaVista. Before the Internet Archive. Before the CDA and DMCA. Before GIFs became ironic.

Surfing really did look, feel and sound as depicted by Hypnospace Outlaw. When I began to look at sites from 1996 — that’s the earliest the Internet Archive preserves — my first thought was the style sheets didn’t load properly.

New technologies gaining prominence later in 1995 further built the foundation for the web we know today — the web woven into our lives so tightly that we freak out when disconnected.

Lycos was another of the early search engines that faded from sight.

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

RealAudio integrated streaming music into the major browsers: Netscape Navigator, Internet Explorer and different flavors of Mosaic, to name a few. The keepers of the HTML standard, the W3C, added forms to the HTML spec, enabling shopping and other transactional tasks. Both Netscape Navigator and IE added Javascript support, paving the way for the modern, interactive web. AltaVista, the first commercial internet-crawling search engine publicly launched.

FutureSplash Animator entered its infancy that year, eventually becoming Macromedia — and later Adobe — Flash. It may have outstayed its welcome, eventually turning into a cumbersome plug-in and security nightmare, but within a few years of its introduction Flash and its counterpart Shockwave turned the static web into the interactive web. And it was an epiphany.

True, the web remained an eyesore for a while longer. When HTML tables and client-side image maps arrived in 1996, richer-navigation graphics and multicolumn layouts finally began to change the look of the web.

Ugly had its charms, though, something that I think today’s slick but more homogenous (science says so!), mobile-optimized designs tend to lack.

Clogged pipes

Of course, bandwidth hampered the visual evolution of the web at the time. Consumer broadband was still a gleam in telecom and cable companies’ eyes. Most people paid $20 to $25 a month to use an online service to connect to the Net on a — at best — blazing 28.8kbps dialup landline connection, but more typically 14.4kbps.

Even imaging giant Kodak used GIF for its site (from December 1996).

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

If it were possible to create today’s CNET home page back then, it could have taken around 11 minutes to load. A frame of the lowest-quality Netflix video would have taken 2.5 seconds (rather than 0.04 second). Even V.90 56kbps (with fax!) was about three years off. Tiny GIFs were preferable to heavy (by the standards of the day) JPEGs.

Nor would you be able to display it on screen. The typical monitor was a hulking 15-inch CRT with 1,024×1,068 resolution — but you probably had to drop to 800×600 if you wanted more than 256 colors, because that’s all a $400 graphics card of the day could handle. If you could figure it out (don’t get me started on the state of the consumer GPU market in the early ’90s) or your cutting-edge $3,700 133MHz PC could handle it.

No free lunches

While the web started to become a lot more useful that year, its loss of innocence accelerated. Conflict among the old-school Internet veterans, the newbies come to play, the businesses seeking to commercialize it — Amazon had just entered the bookselling biz, eBay launched — politicians wanting to control it and a growing class of hackers probing its weaknesses spurred rampant “Wild West” analogies.

1995 was the year the popup ad popped up, starting the race to the bottom of intrusive, interruptive, attention-grabbing tactics that 25 years later give us the overlays, push notification requests, newsletter signups, autoplay and more that pay the bills for the sites that cost you 10 seconds of close-clicking unwanted elements obscuring the page — just to spend two seconds figuring out that a Google-SEO-gamed snippet misled you about the content.

It was the year the browser wars began and antitrust probes launched in anticipation of Microsoft shipping Windows 95 with Internet Explorer and MSN (at the time an online service) built in.

This was the site of the multi-billion dollar Coca Cola company in 1996.

Lori Grunin/CNET

As people flocked to the easy-to-use web it drew increasing attention to the controversial aspects of the internet, such as the exchange of sexual content and copyrighted materials on usenet, ultimately conflating “web” and “internet” forevermore.

Online services started to feel the pressure to monitor subscribers. AOL’s newsworthy decision to include “breast” on its indecent word list (and its subsequent reversal) seems quaint in light of today’s fractures over violence, hate speech and the spread of dangerous lies.

But I also try to imagine how events from that year — the earthquakes in Kobe, Japan, and in Russia; the space shuttle Atlantis docking with the Mir space station and Galileo reaching Jupiter; the Oklahoma City bombing; the OJ Simpson verdict; the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack; the Ebola outbreak in Zaire; the volcano eruption in Montserrat; the Bosnian genocide; the killer US heatwave; and the Brixton riots in the UK, just to name a few — would have played out differently in today’s by-the-minute, web-interconnected, high-bandwidth, phones-everywhere world.

It’s not a big stretch of imagination, though. The web in 1995 was fun, but 25 years later? Pivotal.