A Hesperapis regularis bee checks out a flower of Clarkia cylindrica at Pinnacles National Park. Credit: Tania Jogesh

Study of flowers with 2 kinds of anthers resolves secret that baffled Darwin.

Some flowers utilize a creative method to guarantee reliable pollination by bees, administering pollen slowly from 2 various sets of anthers.

Most blooming plants depend upon pollinators such as bees to move pollen from the male anthers of one flower to the female preconception of another flower, making it possible for fertilization and the production of fruits and seeds. Bee pollination, nevertheless, includes a fundamental dispute of interest, due to the fact that bees are just thinking about pollen as a food source.

“The bee and the plant have different goals, so plants have evolved ways to optimize the behavior of bees to maximize the transfer of pollen between flowers,” discussed Kathleen Kay, associate teacher of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz.

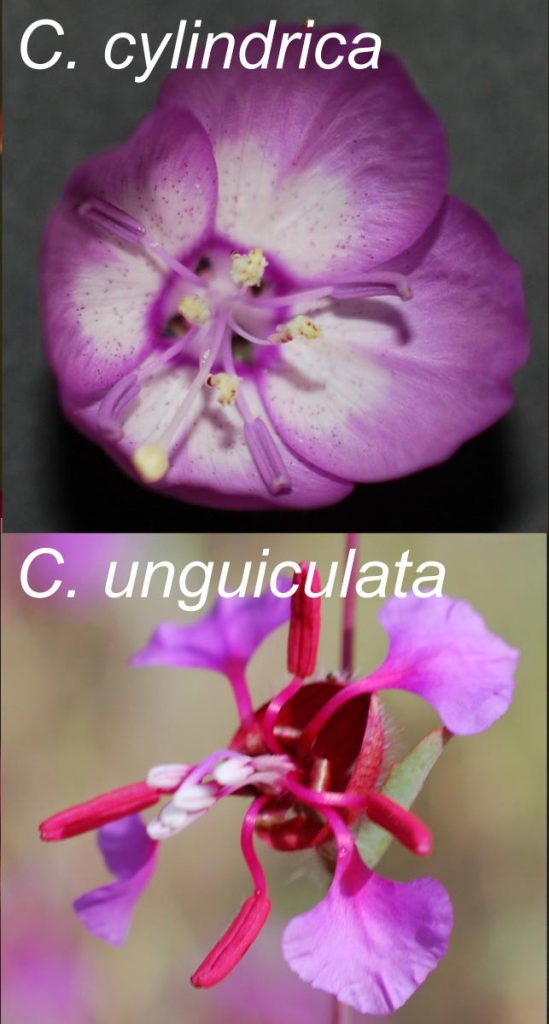

Close-up pictures of Clarkia unguiculata and Clarkia cylindrica flowers reveal the 2 kinds of anthers, a noticeable inner whorl and an external whorl that mixes in with the petals. Credit: Kay et al., PRSB 2020

In a research study released December 23 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Kay’s group explained a pollination method including flowers with 2 unique sets of anthers that vary in color, size, and position. Darwin was dumbfounded by such flowers, regreting in a letter that he had “wasted enormous effort over them, and cannot yet get a glimpse of the meaning of the parts.”

For years, the only description presented for this phenomenon, called heteranthery, was that a person set of anthers is specialized for bring in and feeding bees, while a less noticeable set of anthers surreptitiously cleans them with pollen for transfer to another flower. This “division of labor” hypothesis has actually been checked in numerous types, and although it does appear to use in a couple of cases, lots of research studies have actually stopped working to validate it.

The brand-new research study proposes a various description and demonstrates how it operates in types of wildflowers in the genus Clarkia. Through a range of greenhouse and field experiments, Kay’s group revealed that heteranthery in Clarkia is a method for flowers to slowly provide their pollen to bees over several check outs.

“What’s happening is the anthers open at different times, so the plant is doling out pollen to the bees gradually,” Kay stated.

This “pollen dosing” method is a method of getting the bees to carry on to another flower without stopping to groom the pollen off their bodies and load it away for shipment to their nest. Bees are extremely specialized for pollen feeding, with hairs on their bodies that bring in pollen electrostatically, stiff hairs on their legs for grooming, and structures for keeping pollen on their legs or bodies.

“If a flower doses a bee with a ton of pollen, the bee is in pollen heaven and it will start grooming and then go off to feed its offspring without visiting another flower,” Kay stated. “So plants have different mechanisms for doling out pollen gradually. In this case, the flower is hiding some anthers and gradually revealing them to pollinators, and that limits how much pollen a bee can remove in each visit.”

There have to do with 41 types of Clarkia in California, and about half of them have 2 kinds of anthers. These tend to be pollinated by specialized types of native singular bees. Kay’s group concentrated on bee pollination in 2 types of Clarkia, C. unguiculata (sophisticated clarkia) and C. cylindrica (speckled clarkia).

In these and other heterantherous clarkias, an inner whorl of anthers stands put up in the center of the flower, is aesthetically noticeable, and grows early, launching its pollen initially. An unnoticeable external whorl lies back versus the petals up until after the inner anthers have actually opened. The external anthers then approach the center of the flower and start to launch their pollen slowly. A couple of days later on, the preconception ends up being put up and sticky, prepared to get pollen from another flower.

“In the field, you can see flowers in different stages, and using time-lapse photography we could see the whole sequence of events in individual flowers,” Kay stated.

The department of labor hypothesis needs both sets of anthers to be producing pollen at the exact same time. Kay stated she chose to examine heteranthery after observing clarkia flowers at a field website and recognizing that description didn’t fit. “I could see some flowers where one set was active, and some where the other set was active, but no flowers where both were active at the same time,” she stated.

In C. cylindrica, the 2 sets of anthers produce pollen with various colors, which made it possible for the scientists to track where it was going. Their experiments revealed that pollen from both sets of anthers was gathered for food and was likewise being moved in between flowers, opposing the department of labor hypothesis.

“The color difference was convenient, because otherwise it’s very hard to track pollen,” Kay stated. “We showed that bees are collecting and transporting pollen from both kinds of anthers, so they are not specialized for different functions.”

Kay stated she didn’t recognize just how much time Darwin had actually invested perplexing over heteranthery up until she began studying it herself. “He figured out so many things, it’s hard to find a case where he didn’t figure it out,” she stated. Darwin may have been on the ideal track, however. Shortly prior to his death, he asked for seeds of C. unguiculata to utilize in experiments.

Reference: “Darwin’s vexing contrivance: a new hypothesis for why some flowers have two kinds of anther” by Kathleen M. Kay, Tania Jogesh, Diana Tataru and Sami Akiba, 23 December 2020, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2020.2593

In addition to Kay, the coauthors of the paper consist of postdoctoral scholar Tania Jogesh and 2 UCSC undergrads, Diana Tataru and Sami Akiba. Both trainees finished senior theses on their work and were supported by UCSC’s Norris Center for Natural History.