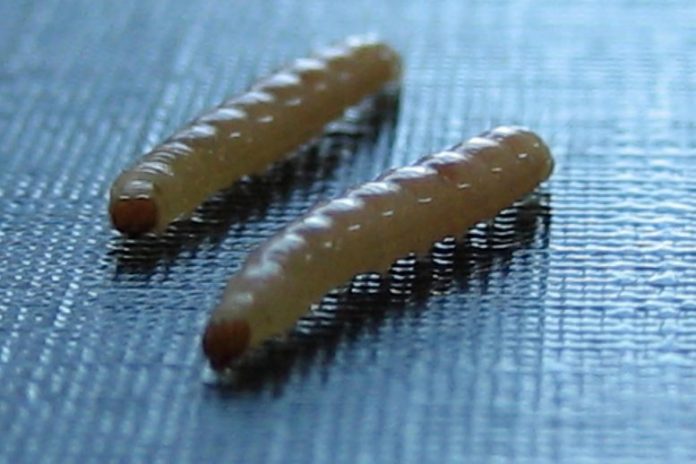

Indian meal moth caterpillars. Credit: M. Boots/UC Berkeley

Study validates evolutionary link in between social structure and selfishness.

One of nature’s most respected cannibals might be concealing in your kitchen, and biologists have actually utilized it to demonstrate how social structure impacts the advancement of self-centered habits.

Researchers exposed that less self-centered habits progressed under living conditions that required people to communicate more regularly with brother or sisters. While the finding was confirmed with insect experiments, Rice University biologist Volker Rudolf stated the evolutionary principal might be used to study any types, consisting of people.

In a research study released in the journal Ecology Letters, Rudolf, long time partner Mike Boots of the University of California, Berkeley, and coworkers revealed they might drive the advancement of cannibalism in Indian meal moth caterpillars with easy modifications to their environments.

Also referred to as weevil moths and kitchen moths, Indian meal moths prevail kitchen insects that lay eggs in cereals, flour and other packaged foods. As larvae, they’re vegetarian caterpillars with one exception: They in some cases consume one another, including their own broodmates.

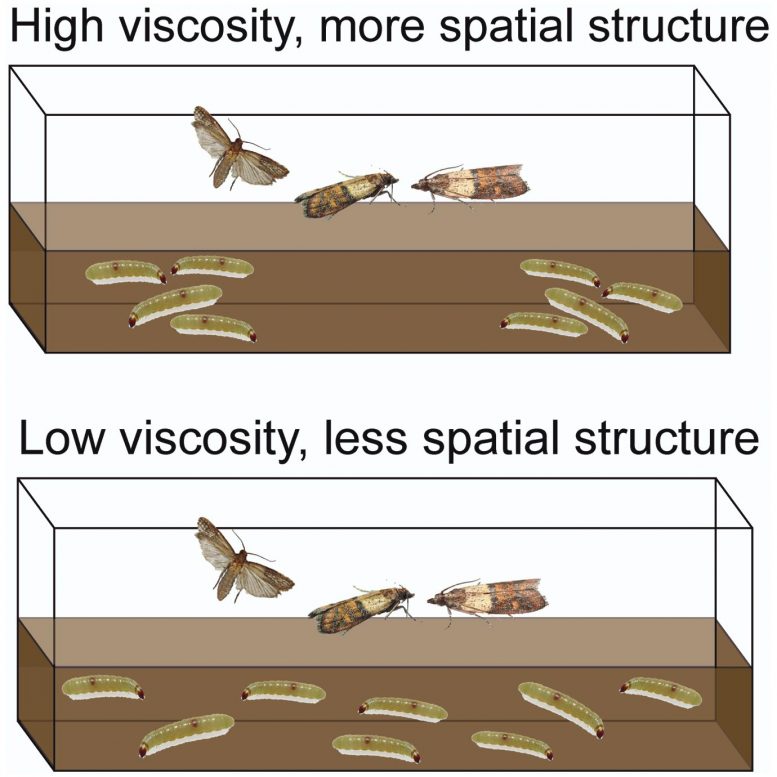

In lab tests, scientists revealed they might naturally increase or reduce rates of cannibalism in Indian meal moths by reducing how far people might wander from one another, and hence increasing the possibility of “local” interactions in between brother or sister larvae. In environments where caterpillars were required to communicate more frequently with brother or sisters, less self-centered habits progressed within 10 generations.

Volker Rudolf is a teacher of biosciences at Rice University. Credit: Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Rudolf, a teacher of biosciences at Rice, stated increased regional interactions stack the deck versus the advancement of self-centered habits like cannibalism.

To comprehend why, he recommends picturing habits can be arranged from least to the majority of self-centered.

“At one end of the continuum are altruistic behaviors, where an individual may be giving up its chance to survive or reproduce to increase reproduction of others,” he stated. “Cannibalism is at the other extreme. An individual increases its own survival and reproduction by literally consuming its own kind.”

Rudolf stated the research study offered an unusual speculative test of a crucial principle in evolutionary theory: As regional interactions increase, so does selective pressure versus self-centered habits. That’s the essence of a 2010 theoretical forecast by Rudolf and Boots, the matching author of the meal moth research study, and Rudolf stated the research study’s findings supported the forecast.

“Families that were highly cannibalistic just didn’t do as well in that system,” he stated. “Families that were less cannibalistic had much less mortality and produced more offspring.”

In the meal moth experiments, Rudolf stated it was relatively simple to make sure that meal moth habits was affected by regional interactions.

“They live in their food,” he stated. “So we varied how sticky it was.”

Indian meal moths were raised for succeeding generations in sealed enclosures where conditions equaled save for the stickiness of their food. In enclosures (top) where food was stickier, caterpillars were most likely to communicate with brother or sisters. Meal moths with more regional interactions with brother or sisters progressed less self-centered habits – as evidenced by lower rates of cannibalism – within 10 generations. Credit: Volker Rudolf/Rice University

Fifteen adult women were positioned in a number of enclosures to lay eggs. The moths lay eggs in food, and larval caterpillars consume and live inside the food up until they pupate. Food abounded in all enclosures, however it differed in stickiness.

“Because they’re laying eggs in clusters, they’re more likely to stay in these little family groups in the stickier foods that limit how fast they can move,” Rudolf stated. “It forced more local interactions, which, in our system, meant more interactions with siblings. That’s really what we think was driving this change in cannibalism.”

Rudolf stated the very same evolutionary principal may likewise be used to the research study of human habits.

“In societies or cultures that live in big family groups among close relatives, for example, you might expect to see less selfish behavior, on average, than in societies or cultures where people are more isolated from their families and more likely to be surrounded by strangers because they have to move often for jobs or other reasons,” he stated.

Rudolf has actually studied the eco-friendly and evolutionary effects of cannibalism for almost 20 years. He discovers it interesting, partially due to the fact that it was misconstrued and understudied for years. Generations of biologists had such a strong hostility to human cannibalism that they crossed out the habits in all types as a “freak of nature,” he stated.

That lastly started to alter gradually a couple of years back, and cannibalism has actually now been recorded in well over 1,000 types and is thought to happen in much more.

“It’s everywhere. Most animals that eat other animals are cannibalistic to some extent, and even those that don’t normally eat other animals — like the Indian meal moth — are often cannibalistic,” Rudolf stated. “There’s no morality attached to it. That’s just a human perspective. In nature, cannibalism is just getting another meal.”

But cannibalism “has important ecological consequences,” Rudolf stated. “It determines dynamics of populations and communities, species coexistence, and even entire ecosystems. It’s definitely understudied for its importance.”

He stated the speculative follow-up to his and Boots’ 2010 theory paper happened nearly by possibility. Rudolf saw an epidemiological research study Boots released a couple of years later on and understood the very same speculative setup might be utilized to check their forecast.

While the moth research study revealed that “limiting dispersal,” and hence increasing regional interactions, can press versus the advancement of cannibalism by increasing the expense of severe selfishness, Rudolf stated the evolutionary push can most likely go the other method also. “If food conditions are poor, cannibalism provides additional benefits, which could push for more selfish behavior.”

He stated it’s likewise possible that a 3rd aspect, kin acknowledgment, might likewise supply an evolutionary push.

“If you’re really good at recognizing kin, that limits the cost of cannibalism,” he stated. “If you recognize kin and avoid eating them, you can afford to be a lot more cannibalistic in a mixed population, which can have evolutionary benefits.”

Rudolf stated he prepares to check out the three-way interaction in between cannibalism, dispersal, and kin acknowledgment in future research studies.

“It would be nice to get a better understanding of the driving forces and be able to explain more of the variation that we see,” he stated. “Like, why are some species extremely cannibalistic? And even within the same species, why are some populations far more cannibalistic than others. I don’t think it’s going to be one single answer. But are there some basic principles that we can work out and test? Is it super-specific to every system, or are there more general rules?”

Reference: “Experimental evidence that local interactions select against selfish behaviour” by Mike Boots, Dylan Childs, Jessica Crossmore, Hannah Tidbury and Volker Rudolf, 23 March 2021, Ecology Letters.

DOI: 10.1111/ele.13734

Additional co-authors consist of Dylan Childs and Jessica Crossmore of the University of Sheffield, and Hannah Tidbury of both the University of Sheffield and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science in Weymouth, England.

The research study was moneyed by the National Science Foundation (1256860, 0841686, 2011109) the National Institutes of Health (R01GM122061) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NEJ0097841).