Life repair of Lystrosaurus in a state of torpor. Credit: Crystal Shin

Researchers find Fossil proof of ‘hibernation-like’ state in tusks of 250-million-year-old Antarctic animal.

Among the numerous winter season survival techniques in the animal world, hibernation is among the most typical. With restricted food and energy sources throughout winter seasons — particularly in locations near or within polar areas — numerous animals hibernate to make it through the cold, dark winter seasons. Though much is understood behaviorally on animal hibernation, it is tough to study in fossils.

According to brand-new research study, this kind of adjustment has a long history. In a paper released on August 27, 2020, in the journal Communications Biology, researchers at Harvard University and the University of Washington report proof of a hibernation-like state in an animal that resided in Antarctica throughout the Early Triassic, some 250 million years back.

The animal, a member of the genus Lystrosaurus, was a remote relative of mammals. Lystrosaurus prevailed throughout the Permian and Triassic durations and are identified by their turtle-like beaks and ever-growing tusks. During Lystrosaurus‘ time, Antarctica lay mainly within the Antarctic Circle and skilled prolonged durations without sunshine each winter season.

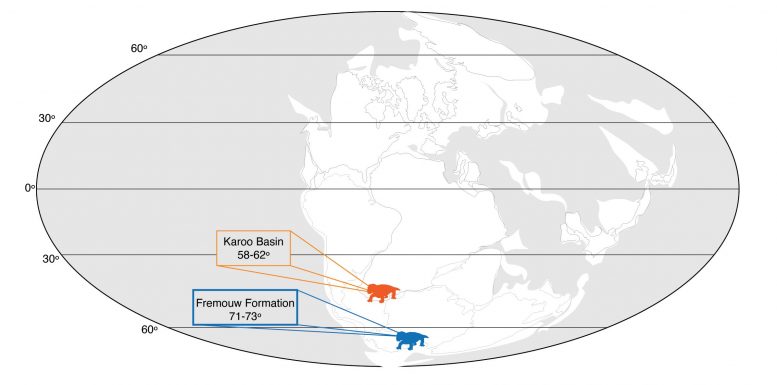

A map of Pangea throughout the Early Triassic, revealing the places of the Antarctic (blue) and South African (orange) Lystrosaurus populations compared in this research study. Credit: Megan Whitney/Christian Sidor

“Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there,” stated lead author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral scientist at Harvard University in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, who performed this research study as a UW doctoral trainee in biology. “These preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one.”

The Lystrosaurus fossils are the earliest proof of a hibernation-like state in a vertebrate animal and suggest that torpor — a basic term for hibernation and comparable states in which animals momentarily lower their metabolic rate to survive a difficult season — developed in vertebrates even prior to mammals and dinosaurs progressed.

Lystrosaurus developed prior to Earth’s biggest mass termination at the end of the Permian Period — which eliminated 70% of vertebrate types on land — and in some way made it through. It went on to live another 5 million years into the Triassic Period and spread out throughout swathes of Earth’s then-single continent, Pangea, that included what is now Antarctica. “The reality that Lystrosaurus made it through completion-Permian mass termination and had such a vast array in the early Triassic has actually made them an extremely well-studied group of animals for comprehending survival and adjustment,” stated co-author Christian Sidor, a UW teacher of biology and manager of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum.

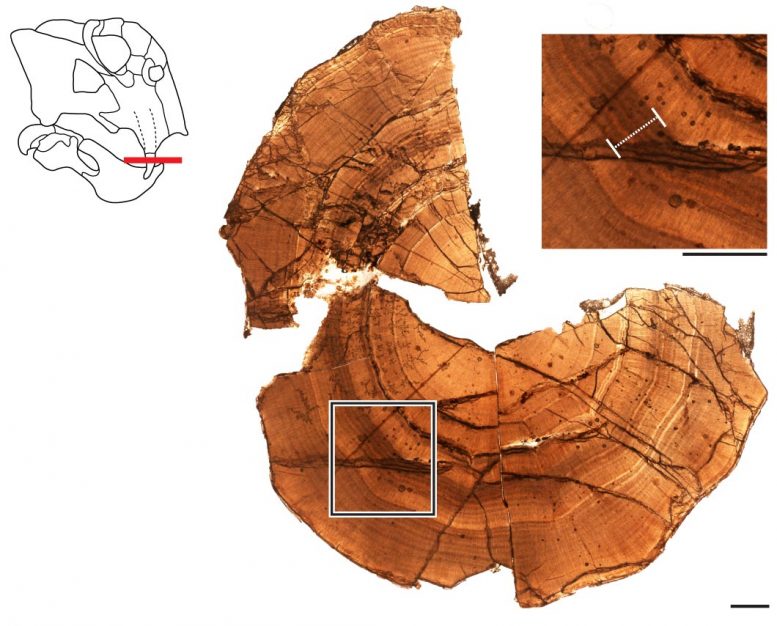

This thin-section of the fossilized tusk from an Antarctic Lystrosaurus reveals layers of dentine transferred in rings of development. The tusk grew inward, with the earliest layers at the edge and the youngest layers near the center, where the pulp cavity would have been. At the leading right is a close-up view of the layers, with a white bar highlighting a zone a sign of a hibernation-like state. Scale bar is 1 millimeter. Credit: Megan Whitney/Christian Sidor

Today, paleontologists discover Lystrosaurus fossils in India, China, Russia, parts of Africa and Antarctica. The animals grew to be 6 to 8 feet long, had no teeth, however bore a set of tusks in the upper jaw. The tusks made Whitney and Sidor’s research study possible due to the fact that, like elephants, Lystrosaurus tusks grew constantly throughout their lives. Taking cross-sections of the fossilized tusks exposed details about Lystrosaurus metabolic process, development and tension or pressure. Whitney and Sidor compared cross-sections of tusks from 6 Antarctic Lystrosaurus to cross-sections of 4 Lystrosaurus from South Africa. During the Triassic, the collection websites in Antarctica were approximately 72 degrees south latitude — well within the Antarctic Circle. The collection websites in South Africa were more than 550 miles north, far outside the Antarctic Circle.

The tusks from the 2 areas revealed comparable development patterns, with layers of dentine transferred in concentric circles like tree rings. The Antarctic fossils, nevertheless, held an extra function that was unusual or missing in tusks further north: closely-spaced, thick rings, which likely suggest durations of less deposition due to extended tension, according to the scientists. “The closest analog we can discover to the ‘stress marks’ that we observed in Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks are tension marks in teeth related to hibernation in specific contemporary animals,” stated Whitney.

University of Washington paleontologist

Christian Sidor excavating fossils in Antarctica in 2017. Credit: Megan Whitney

The scientists cannot definitively conclude that Lystrosaurus went through real hibernation. The tension might have been brought on by another hibernation-like kind of torpor, such as a more short-term decrease in metabolic process. Lystrosaurus in Antarctica most likely required some kind of hibernation-like adjustment to deal with life near the South Pole, stated Whitney. Though Earth was much warmer throughout the Triassic than today — and parts of Antarctica might have been forested — plants and animals listed below the Antarctic Circle would still experience severe yearly variations in the quantity of daytime, with the sun missing for extended periods in winter season.

Many other ancient vertebrates at high latitudes might likewise have actually utilized torpor, consisting of hibernation, to deal with the pressures of winter season, Whitney stated. But numerous well-known extinct animals, consisting of the dinosaurs that progressed and spread out after Lystrosaurus passed away out, don’t have teeth that grow constantly.

Megan Whitney, then a University of

Washington doctoral trainee, excavating fossils in

Antarctica in 2017. Whitney is now a paleontologist at

Harvard University. Credit: Christian Sidor

“To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought on by hibernation, you need to look at something that can fossilize and was growing continuously during the animal’s life,” stated Sidor. “Many animals don’t have that, however thankfully Lystrosaurus did.” If analysis of extra Antarctic and South African Lystrosaurus fossils verifies this discovery, it might likewise settle another dispute about these ancient, hearty animals. “Cold-blooded animals often shut down their metabolism entirely during a tough season, but many endothermic or ‘warm-blooded’ animals that hibernate frequently reactivate their metabolism during the hibernation period,” stated Whitney. “What we observed in the Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks fits a pattern of little metabolic ‘reactivation events’ throughout a duration of tension, which is most comparable to what we see in warm-blooded hibernators today.” If so, this far-off cousin of mammals is a suggestion that numerous functions of life today might have been around for numerous countless years prior to people progressed to observe them.

Read Evidence of “Hibernation-Like” State Discovered in Early Triassic Creature for more on this discovery.

Reference: “Evidence of torpor in the tusks of Lystrosaurus from the Early Triassic of Antarctica” by Megan R. Whitney and Christian A. Sidor, 27 August 2020, Communications Biology.

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-020-01207-6

The research study was moneyed by the National Science Foundation. Grant numbers: PLR-1341304, DEBORAH-1701383.