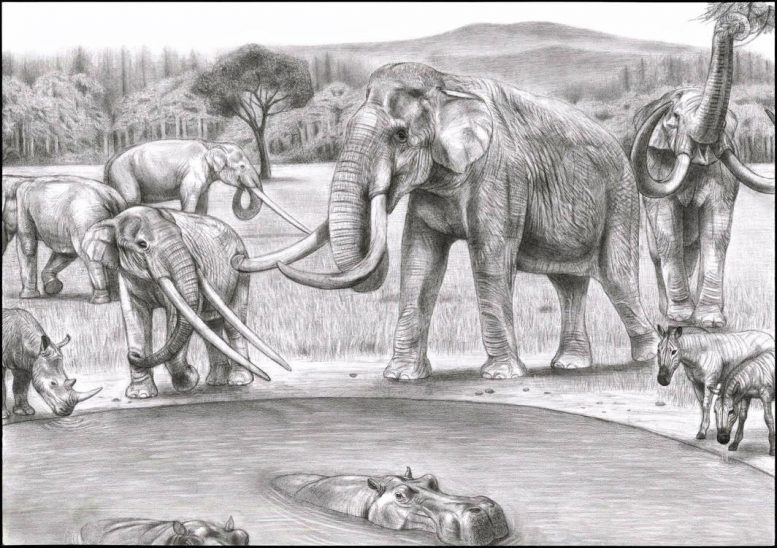

Dusk falls on East Africa’s Turkana Basin 4 million years earlier, where our early upright-walking ape forefathers, Australopithecus anamensis (foreground), shared their environment with numerous existing side-by-side proboscidean types, as part of a magnificent herbivore neighborhood consisting of some progenitors these days’s charming East African animals. Background (delegated right): Anancus ultimus, last of the African mastodonts; Deinotherium bozasi, gigantic herbivore as high as a giraffe; Loxodonta adaurora, enormous extinct cousin of modern-day African elephants, along with the closely-related, smaller sized L. exoptata. Middle ground (delegated right): Eurygnathohippus turkanense, zebra-sized three-hoofed horse; Tragelaphus kyaloae, a leader of the nyala and kudu antelopes; Diceros praecox – forefather of the modern-day black rhino. Credit: Julius Csotonyi

Elephants and their forefathers were pressed into wipeout by waves of severe international ecological modification, instead of overhunting by early human beings, according to brand-new research study.

The research study, released today (July 1, 2021) in Nature Ecology & Evolution, challenges claims that early human hunters butchered ancient elephants, mammoths, and mastodonts to termination over centuries. Instead, its findings show the termination of the last mammoths and mastodonts at completion of the last Ice Age marked the end of progressive climate-driven international decrease amongst elephants over countless years.

Highly total fossil skull of a common mid Miocene ‘shovel-tusker’, Platybelodon grangeri, wandered in big herds throughout Central Asia 13 million years earlier. The specimen is screen installed at the Hezheng Paleozoological Museum, Gansu Province, China. Credit: Zhang Hanwen

Although elephants today are limited to simply 3 threatened types in the African and Asian tropics, these are survivors of a once even more varied and extensive group of huge herbivores, referred to as the proboscideans, which likewise consist of the now totally extinct mastodonts, stegodonts, and deinotheres. Only 700,000 years earlier, England was house to 3 kinds of elephants: 2 huge types of mammoths and the similarly prodigious straight-tusked elephant.

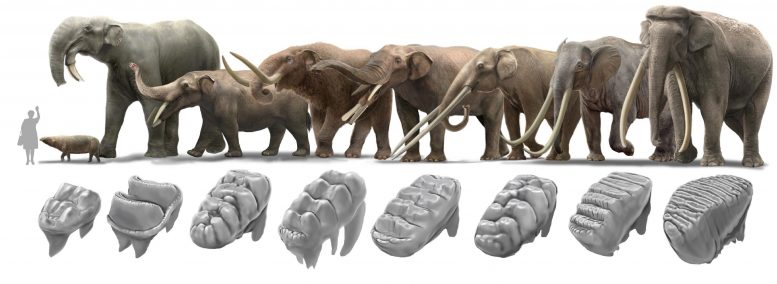

An global group of paleontologists from the universities of Alcalá, Bristol, and Helsinki, piloted the most in-depth analysis to date increasing and fall of elephants and their predecessors, which took a look at how 185 various types adjusted, covering 60 million years of advancement that started in North Africa. To probe into this abundant evolutionary history, the group surveyed museum fossil collections around the world, from London’s Natural History Museum to Moscow’s Paleontological Institute. By examining qualities such as body size, skull shape, and the chewing surface area of their teeth, the group found that all proboscideans fell within among 8 sets of adaptive techniques.

“Remarkably for 30 million years, the entire first half of proboscidean evolution, only two of the eight groups evolved,” stated Dr. Zhang Hanwen, research study coauthor and Honorary Research Associate at the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences.

“Most proboscideans over this time were nondescript herbivores ranging from the size of a pug to that of a boar. A few species got as big as a hippo, yet these lineages were evolutionary dead-ends. They all bore little resemblance to elephants.”

A scene from northern Italy 2 million years earlier – the primitive southern mammoths Mammuthus meridionalis (right-hand side) sharing their watering hole with the mastodont-grade Anancus arvernensis (left-hand side), the last of its kind. Other animals that brought an ‘East African air’ to Tuscany consisted of rhinos, hippos and zebra-like wild horses. Credit: Tamura Shuhei

The course of proboscidean advancement altered considerably some 20 million years earlier, as the Afro-Arabian plate clashed into the Eurasian continent. Arabia supplied vital migration passage for the diversifying mastodont-grade types to check out brand-new environments in Eurasia, and after that into North America by means of the Bering Land Bridge.

“The immediate impact of proboscidean dispersals beyond Africa was quantified for the very first time in our study,” stated lead author Dr. Juan Cantalapiedra, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Alcalá in Spain.

“Those archaic North African species were slow-evolving with little diversification, yet we calculated that once out of Africa proboscideans evolved 25 times faster, giving rise to a myriad of disparate forms, whose specializations permitted niche partition between several proboscidean species in the same habitats. One case in point being the massive, flattened lower tusks of the ‘shovel-tuskers’. Such coexistence of giant herbivores was unlike anything in today’s ecosystems.”

The gallery of extinct proboscideans in the Muséum nationwide d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, echoing their bygone golden era. Credit: Zhang Hanwen

Dr. Zhang included: “The aim of the game in this boom period of proboscidean evolution was ‘adapt or die’. Habitat perturbations were relentless, pertained to the ever-changing global climate, continuously promoting new adaptive solutions while proboscideans that didn’t keep up were literally, left for dead. The once greatly diverse and widespread mastodonts were eventually reduced to less than a handful of species in the Americas, including the familiar Ice Age American mastodon.”

By 3 million years ago the elephants and stegodonts of Africa and eastern Asia relatively emerged triumphant in this constant evolutionary cog. However, ecological interruption linked to the coming Ice Ages struck them hard, with making it through types required to adjust to the brand-new, more austere environments. The most severe example was the woolly massive, with thick, shaggy hair and huge tusks for recovering plants covered under thick snow.

The group’s analyses recognized last proboscidean termination peaks beginning at around 2.4 million years earlier, 160,000 and 75,000 years ago for Africa, Eurasia, and the Americas, respectively.

Disparity of proboscidean kinds through 60 million years of advancement. Early proboscideans like Moeritherium (far left) were nondescript herbivores generally the size of a pig. But subsequent advancement of this family tree was practically regularly controlled by enormous types, lots of significantly bigger than today’s elephants (e.g. Deinotherium second left; Palaeoloxodon outermost right). An essential aspect of proboscidean evolutionary development lies with variations in tooth morphology. Credit: Óscar Sanisidro

“It is important to note that these ages do not demarcate the precise timing of extinctions, but rather indicate the points in time at which proboscideans on the respective continents became subject to higher extinction risk,” stated Dr. Cantalapiedra.

Unexpectedly, the outcomes do not associate with the growth of early human beings and their boosted abilities to hound megaherbivores.

“We didn’t foresee this result. It appears as if the broad global pattern of proboscidean extinctions in recent geological history could be reproduced without accounting for impacts of early human diasporas. Conservatively, our data refutes some recent claims regarding the role of archaic humans in wiping out prehistoric elephants, ever since big game hunting became a crucial part of our ancestors’ subsistence strategy around 1.5 million years ago,” stated Dr. Zhang.

“Although this isn’t to say we conclusively disproved any human involvement. In our scenario, modern humans settled on each landmass after proboscidean extinction risk had already escalated. An ingenious, highly adaptable social predator like our species could be the perfect black swan occurrence to deliver the coup de grâce.”

Reference: “The rise and fall of proboscidean ecological diversity” by Juan L. Cantalapiedra, Óscar Sanisidro, Hanwen Zhang, María T. Alberdi, José L. Prado, Fernando Blanco and Juha Saarinen, 1 July 2021, Nature Ecology & Evolution.

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-021-01498-w