About 66 million years earlier, a substantial asteroid crashed into what is now the Yucatan, plunging the Earth into darkness. The effect changed tropical rain forests, triggering the reign of flowers.

Tropical rain forests today are biodiversity hotspots and play a crucial function worldwide’s environment systems. A brand-new research study released today in Science clarifies the origins of contemporary rain forests and might assist researchers comprehend how rain forests will react to a quickly altering environment in the future.

The research study led by scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) reveals that the asteroid effect that ended the reign of dinosaurs 66 million years ago likewise triggered 45% of plants in what is now Colombia to go extinct, and it gave way for the reign of blooming plants in contemporary tropical rain forests.

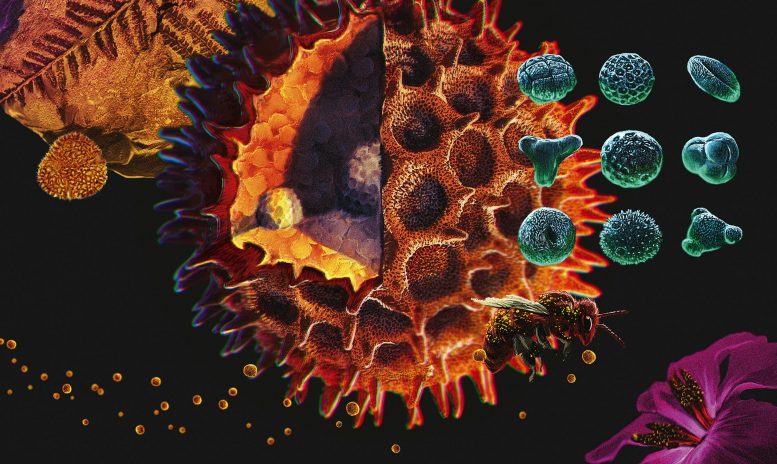

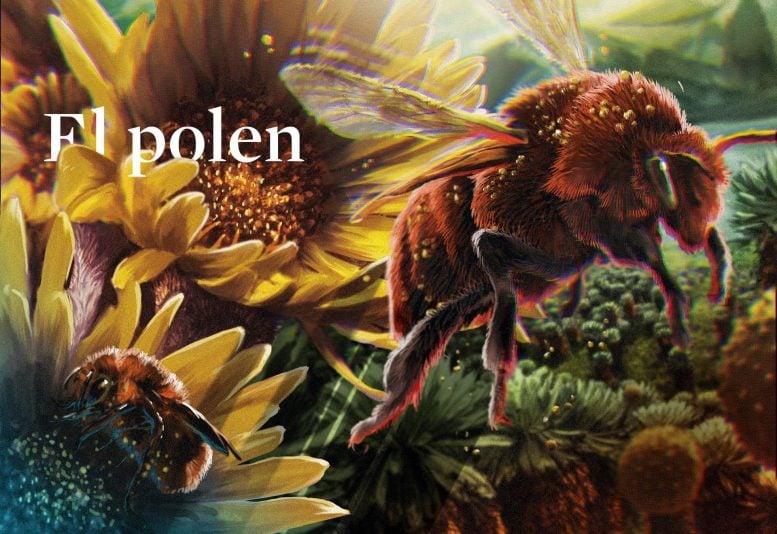

From forests filled with ferns to forests filled with flowers: Plants started to produce appealing flowers including sweet benefits for bugs who bring pollen grains (generally the male sperm of the plants) to other flowers, assisting plants replicate. This method was so effective that blooming plants took control of tropical forests, and the world. Credit: Hace Tiempo. Un viaje paleontologico ilustrado por Colombia. Instituto Alexander von Humboldt e Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Tropicales. Banco de Imágenes (BIA), Instituto Alexander von Humboldt.

“We wondered how tropical rainforests changed after a drastic ecological perturbation such as the Chicxulub impact, so we looked for tropical plant fossils,” stated Mónica Carvalho, initially author and joint postdoctoral fellow at STRI and at the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia. “Our team examined over 50,000 fossil pollen records and more than 6,000 leaf fossils from before and after the impact.”

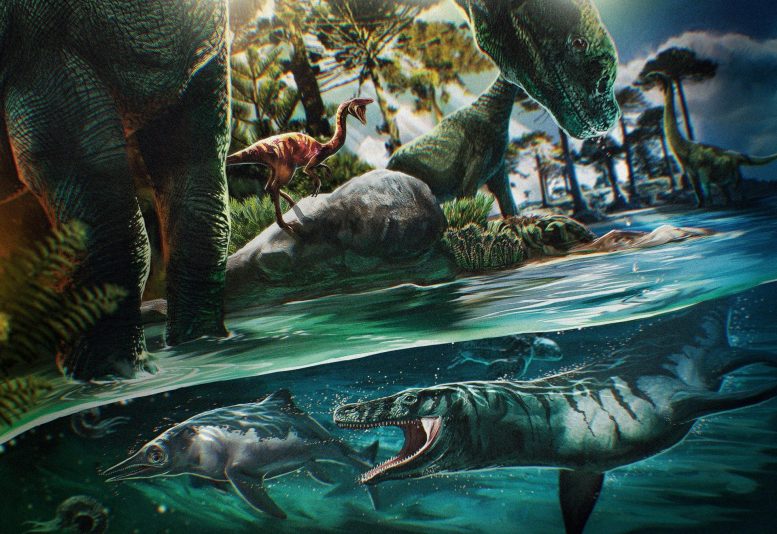

125 to 100 million years earlier, throughout the reign of the dinosaurs, much of what is now Colombia was covered in forests controlled by conifers and ferns. Credit: Hace Tiempo. Un viaje paleontologico ilustrado por Colombia. Instituto Alexander von Humboldt e Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Tropicales. Banco de Imágenes (BIA), Instituto Alexander von Humboldt.

In Central and South America, geologists hustle to discover fossils exposed by roadway cuts and mines prior to heavy rains clean them away and the jungle conceals them once again. Before this research study, little was understood about the result of this termination on the development of blooming plants that now control the American tropics.

Carlos Jaramillo, personnel paleontologist at STRI and his group, mainly STRI fellows—a lot of them from Colombia—studied pollen grains from 39 websites that consist of rock outcrops and cores drilled for oil expedition in Colombia, to paint a huge, local image of forests prior to and after the effect. Pollen and spores acquired from rocks older than the effect reveal that rain forests were similarly controlled by ferns and blooming plants. Conifers, such as loved ones of the Kauri pine and Norfolk Island pine, offered in grocery stores at Christmas time (Araucariaceae), prevailed and cast their shadows over dinosaur routes. After the effect, conifers vanished nearly entirely from the New World tropics, and blooming plants took control of. Plant variety did not recuperate for around 10 million years after the effect.

After the asteroid effect in Mexico, nearly half of the plants existing prior to the effect ended up being extinct. After the effect, blooming plants concerned control contemporary tropical forests.. Credit: Hace Tiempo. Un viaje paleontologico ilustrado por Colombia. Instituto Alexander von Humboldt e Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Tropicales. Banco de Imágenes (BIA), Instituto Alexander von Humboldt.

Leaf fossils informed the group much about the previous environment and regional environment. Carvalho and Fabiany Herrera, postdoctoral research study partner at the Negaunee Institute for Conservation Science and Action at the Chicago Botanic Garden, led the research study of over 6,000 specimens. Working with Scott Wing at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and others, the group discovered proof that pre-impact tropical forest trees were spaced far apart, permitting light to reach the forest flooring. Within 10 million years post-impact, some tropical forests were thick, like those these days, where leaves of trees and vines cast deep shade on the smaller sized trees, bushes, and herbaceous plants listed below. The sparser canopies of the pre-impact forests, with less blooming plants, would have moved less soil water into the environment than did those that matured in the countless years later.

“It was simply as rainy back in the Cretaceous, however the forests worked in a different way,” Carvalho stated.

Modern Bogotá is an Andean city at nearly 3000m (9000 feet) above water level. But in the Paleocene (the 10-million-year duration following the asteroid effect) it was covered by tropical forest. Insect damage on fossil leaves gathered near Bogotá informs scientists that after the effect, bugs that fussy eaters (bugs that just consumed a specific types) ended up being less typical, changed by bugs with more broad taste that might consume several plants. Credit: Hace Tiempo. Un viaje paleontologico ilustrado por Colombia. Instituto Alexander von Humboldt e Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Tropicales. Banco de Imágenes (BIA), Instituto Alexander von Humboldt.

The group discovered no proof of bean trees prior to the termination occasion, however later there was a terrific variety and abundance of bean leaves and pods. Today, vegetables are a dominant household in tropical rain forests, and through associations with germs, take nitrogen from the air and turn it into fertilizer for the soil. The increase of vegetables would have drastically impacted the nitrogen cycle.

Carvalho likewise dealt with Conrad Labandeira at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History to study insect damage on the leaf fossils.

From 66 to 100 million years earlier, blooming plants started to diversify in water level swamps and lowland forests, where the Andes mountains are today. Credit: Hace Tiempo. Un viaje paleontologico ilustrado por Colombia. Instituto Alexander von Humboldt e Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Tropicales. Banco de Imágenes (BIA), Instituto Alexander von Humboldt.

“Insect damage on plants can reveal in the microcosm of a single leaf or the expanse of a plant community, the base of the trophic structure in a tropical forest,” Labandeira stated. “The energy residing in the mass of plant tissues that is transmitted up the food chain—ultimately to the boas, eagles and jaguars—starts with the insects that skeletonize, chew, pierce and suck, mine, gall and bore through plant tissues. The evidence for this consumer food chain begins with all the diverse, intensive and fascinating ways that insects consume plants.”

“Before the impact, we see that different types of plants have different damage: feeding was host-specific,” Carvalho stated. “After the impact, we find the same kinds of damage on almost every plant, meaning that feeding was much more generalistic.”

Fossil leaves from the collection utilized for this research study. Heavily insect-fed spurge leaves from the 58-60 Myr-old Neotropical rain forests of the Bogotá Formation in Colombia. Today, the spurge household is among the most plentiful and varied in lowland tropical rain forests. Credit: from Monica Carvalho.

How did the after results of the effect change sporadic, conifer-rich tropical forests of the dinosaur age into the rain forests these days—towering trees dotted with yellow, purple and pink blooms, leaking with orchids? Based on proof from both pollen and leaves, the group proposes 3 descriptions for the modification, all of which might be proper. One concept is that dinosaurs kept pre-impact forests open by feeding and moving through the landscape. A 2nd description is that falling ash from the effect enriched soils throughout the tropics, offering a benefit to the faster-growing blooming plants. The 3rd description is that preferential termination of conifer types developed a chance for blooming plants to take control of the tropics.

“Our study follows a simple question: How do tropical rainforests evolve?” Carvalho stated. “The lesson learned here is that under rapid disturbances—geologically speaking—tropical ecosystems do not just bounce back; they are replaced, and the process takes a really long time.”

Short zoom interview clip with very first author and post-doctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia. She responds to the concern: What was the most amazing part of the task for you? Credit: Ana Endara, STRI

Reference: “Extinction at the end-Cretaceous and the origin of modern Neotropical rainforests” by Mónica R. Carvalho, Carlos Jaramillo, Felipe de la Parra, Dayenari Caballero-Rodríguez, Fabiany Herrera, Scott Wing, Benjamin L. Turner, Carlos D’Apolito, Millerlandy Romero-Báez, Paula Narváez, Camila Martínez, Mauricio Gutierrez, Conrad Labandeira, German Bayona, Milton Rueda, Manuel Paez-Reyes, Dairon Cárdenas, Álvaro Duque, James L. Crowley, Carlos Santos and Daniele Silvestro, 2 April 2021, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abf1969

The authors of this paper are associated with STRI in Panama, the Universidad del Rosario Bogota, Colombia; The Université de Montpellier, CNRS, EPHE, IRD, France; Universidad de Salamanca, Spain; the Instituto Colombiano del Petróleo, Bucaramanga, Colombia; the Chicago Botanic Garden; National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.,; University of Florida, U.S.; Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, Brazil; ExxonMobil Corporation, Spring, Texas, U.S.; Centro Científico Tecnológico-CONICET, Mendoza, Argentina; Universidad de Chile, Santiago; University of Maryland, College Park, U.S.; Capital Normal University, Beijing, China; Corporación Geológica Ares, Bogota, Colombia; Paleoflora Ltda., Zapatoca, Colombia; University of Houston, Texas, U.S.; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas SINCHI, Leticia, Colombia; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia; Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, U.S.; BP Exploration Co. Ltd., UK; and University of Fribourg, Switzerland.