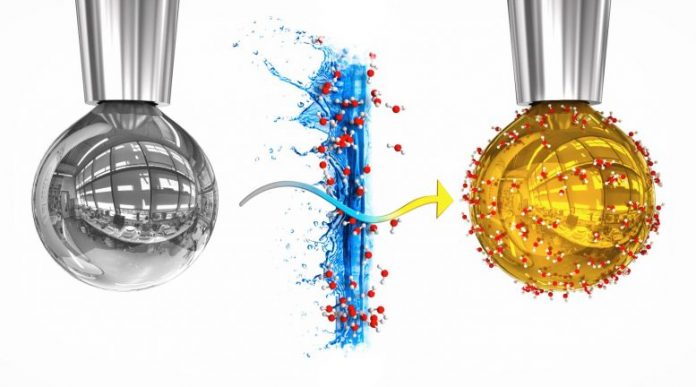

On the left is a pure drop of sodium-potassium alloy, on the right is the drop with a layer of water, in which electrons freed from the metal liquified, providing it a golden metal shine. Credit: Artistic rendering by Tomáš Belloň / IOCB Prague

Pure water is not a great conductor of electrical power. It is, in truth, an electrical insulator. In order to perform electrical power, water should consist of liquified salts, for instance, yet the conductivity of such an electrolyte is fairly low, a number of orders lower than that of metals. Is it possible to produce water that is as conductive as, state, copper wire?

Scientists have actually assumed that this might occur in the cores of big worlds, where high pressure compresses water particles to the point that their electron shells start to overlap. At present, producing that sort of pressure on Earth surpasses human abilities, and it was for that reason presumed that preparing metal water under terrestrial conditions would stay an evasive objective for the foreseeable future. However, a worldwide group of scientists headed by Pavel Jungwirth of IOCB Prague has actually established a brand-new approach with which they was successful in making metal water under terrestrial conditions that lasted for a number of seconds. Their paper was just recently released in Nature.

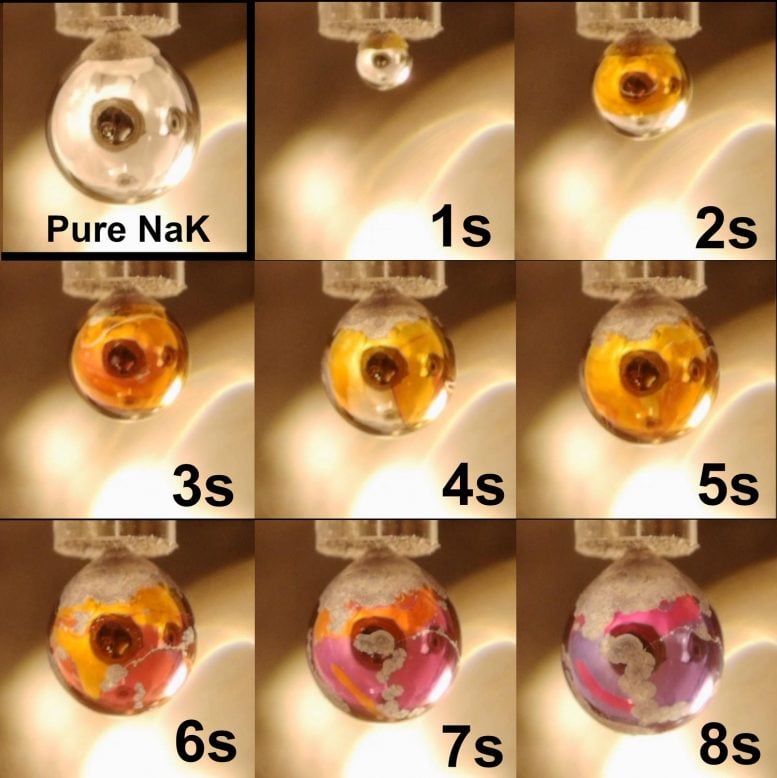

The drop of sodium-potassium alloy exposed to the action of the water vapor at 10-4 mbar. A layer of water types on the drop, in which electrons freed from the metal liquify, providing it a golden metal shine. Credit: Phil Mason / IOCB Prague

The concept of utilizing tremendous pressure to make metal out of water is absolutely nothing brand-new. In concept, it ought to be possible to compress water particles to the point that their electron shells start to overlap and form a so-called conduction band comparable to the one in metal products. The necessary pressure of 50 Mbar (i.e. around 50 million times higher than on the surface area of Earth) can be discovered in the cores of big worlds, however we are not yet able to attain it under terrestrial conditions.

Dissolution of electrons

In partnership with scientists from the University of Southern California, the Fritz Haber Institute, and other institutes, Jungwirth’s group just recently established an approach that has actually permitted them to prepare metal water while entirely avoiding the requirement for high pressure. The approach constructs on earlier research study of the Pavel Jungwirth Group concentrating on the habits of alkali metals in water and liquid ammonia. Inspired by deal with alkali metal-liquid ammonia services, which at high concentrations act like a metal, the scientists chose to try production of a conduction band not by compressing water particles however rather by method of enormous dissolution of the electrons launched from the alkali metal. In doing so, nevertheless, they needed to get rid of a basic barrier: on intro to water, alkali metals right away blow up.

The very first image reveals a pure drop of sodium-potassium alloy; in the next images, we see the drop exposed to the action of the water vapor at 10-4 mbar. A layer of water types on the drop, in which electrons freed from the metal liquify, providing it a golden metal shine. Credit: Phil Mason / IOCB Prague

“Throwing sodium into water is one of the most popular school experiments and the subject of many a YouTube video. As is well known, when you throw a chunk of sodium in water, you don’t get metallic water but an immediate and substantial explosion that takes out your apparatus,” states Jungwirth, who heads a group at IOCB Prague focusing on molecular modeling. “In order to contain this intense and, for laboratory purposes, rather counterproductive chemistry, we approached it the other way around; instead of adding the alkali metal to the water, we added the water to the metal.”

Golden drop of metal water

Inside a vacuum chamber, the scientists exposed a drop of sodium-potassium alloy to a percentage of water vapor, which started to condense on its surface area. The electrons freed from the alkali metal liquified in the layer of water on the surface area quicker than the chain reaction that leads to the surge. There were an enough variety of them to get rid of the important limitation for the development of a conduction band and therefore trigger a metal water service, which in addition to the electrons likewise included liquified alkali cations and chemically formed hydroxide and hydrogen.

A pure drop of sodium-potassium alloy. Credit: Phil Mason / IOCB Prague

“Thanks to this, we were able to create a thin layer of gold-colored metallic water solution that lasted for several seconds, and that was enough for us to not only see it with our own eyes but also measure it with spectrometers,” states Jungwirth, including: “We more or less jury-rigged the necessary apparatus in a small lab at our institute in Prague, which is also where the fist experiments took place. We then obtained the key evidence for the presence of metallic water using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy on the synchrotron in Berlin.”

The drop of sodium-potassium alloy exposed to the action of the water vapor at 10-4 mbar. A layer of water formed on the drop, in which electrons freed from the metal liquified, providing it a golden metal shine. Credit: Phil Mason / IOCB Prague

The research study of the scientists at IOCB Prague and their coworkers not just reveals that metal water can be prepared under terrestrial conditions, however it likewise supplies a comprehensive characterization of the spectroscopic homes linked to its gorgeous golden metal shine.

Prof. Pavel Jungwirth, head of the Molecular Modeling Group at IOCB Prague. Credit: Tomas Bellon / IOCB Prague

Reference: “Spectroscopic evidence for a gold-coloured metallic water solution” by Philip E. Mason, H. Christian Schewe, Tillmann Buttersack, Vojtech Kostal, Marco Vitek, Ryan S. McMullen, Hebatallah Ali, Florian Trinter, Chin Lee, Daniel M. Neumark, Stephan Thürmer, Robert Seidel, Bernd Winter, Stephen E. Bradforth and Pavel Jungwirth, 28 July 2021, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03646-5