May 29, 2021

One of the world’s biggest deltas stands as an impressive example of how water and ice can form the land.

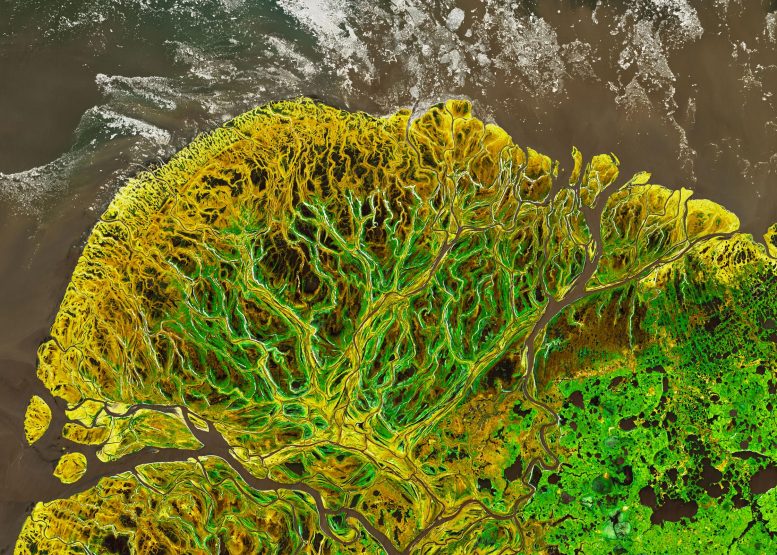

The Yukon-Kuskokswim Delta is among the world’s biggest deltas, and it stands as an impressive example of how water and ice can form the land. These images reveal the delta’s northern lobe, where the Yukon River spills into the Bering Sea along the west coast of Alaska.

“The Yukon Delta is an exceptionally vivid landscape, whether viewed from the ground, from the air, or from low-Earth orbit,” stated Gerald Frost, a researcher at ABR, Inc.—Environmental Research and Services in Fairbanks, Alaska. The vibrant landscape is recorded in these images gotten with the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 on May 29, 2021. The images are composites, mixing natural-color images of water with a false-color picture of the land.

While the image might be thought about an artwork, there are some helpful elements to taking a look at the land in this manner. For example, you can quickly differentiate locations of live greenery (green) from land that is bare or includes dead greenery (light brown) from the network of sediment-rich rivers and ponded flood water (dark brown). A scattering of thermokarst lakes are likewise part of the scene.

May 29, 2021

In basic, the green locations throughout the delta are high willow shrublands. They are particularly obvious on either side of the river channels in the in-depth image above. The light-brown locations are mostly damp sedge meadows; they appear brown because much of it is the dead remains of in 2015’s development. Away from the delta (ideal side of the image) the greenery is shrub-tussock tundra.

“To me, one of the interesting things about the delta is that it is a highly transitional area, with some elements of Arctic tundra and some of boreal forest,” Frost stated.

The delta likewise transitions with the seasons. At the time of this image, the signature of spring flooding is composed throughout the delta. Melting snow and ice trigger the rivers to overflow their banks and by late May, a number of the marshes are filled with floodwater, which looks like dark-brown ponds.

According to Lawrence Vulis, a college student at the University of California, Irvine, the delta would have appeared a lot more flooded right away following the melting of snow and ice a couple of weeks prior to this image. Stream determines and satellite images recommend that the bulk of the flooding had actually currently decreased. Still, the flooding was current enough that the lots of ponding stayed on May 29. As summer season advances, the floodwater will continue to decline and the wetlands will continue to green up with greenery.

Also observe the vibrant water where the delta satisfies the Bering Sea. This is an item of glacial overflow far upstream, which brings a big quantity of sediment towards the coast. This sediment is likewise crucial to the development of high “levees” on the sides of the channels, transferred there when floodwaters overflow their banks. These “levees” support stands of high willows—crucial environment for moose.

“Interestingly, tall shrubs have expanded a lot on the delta in recent decades, and the moose have followed,” Frost stated. “Today, the delta has one of the highest moose densities in the state of Alaska.”

The delta did not constantly look in this manner. Studies have actually revealed that the contemporary Yukon Delta is simply a couple of thousand years of ages. It’s young age “is incredible to think about,” Vulis stated. “We are used to thinking about relatively ancient landscapes, but modern river deltas have only formed in the last 10,000 to 8,000 years since global sea level has stabilized.”

The delta might rather perhaps look various in the future. “The Yukon and other Arctic deltas are thought to be particularly vulnerable to climate change,” Vulis kept in mind, “due to the roles of permafrost and ice in shaping these deltas.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, utilizing Landsat information from the U.S. Geological Survey.