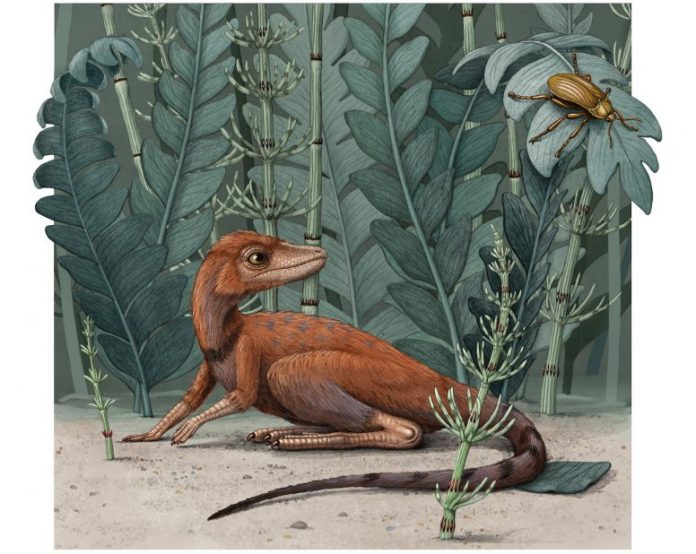

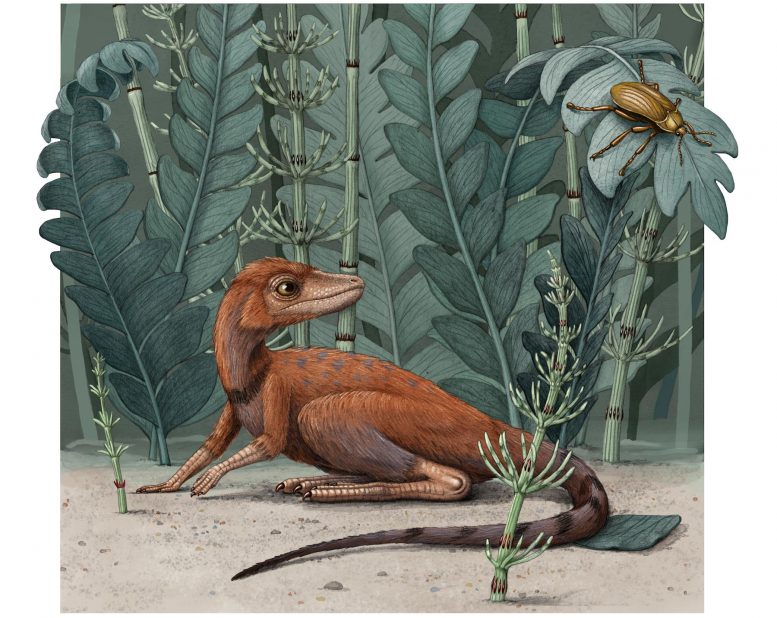

Illustration of Kongonaphon kely, a recently explained reptile near the origins of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, in what would have been its natural surroundings in the Triassic (~237 million years ago). Credit: Alex Boersma

New research study recommends a miniaturized origin for a few of the biggest animals ever to survive on Earth.

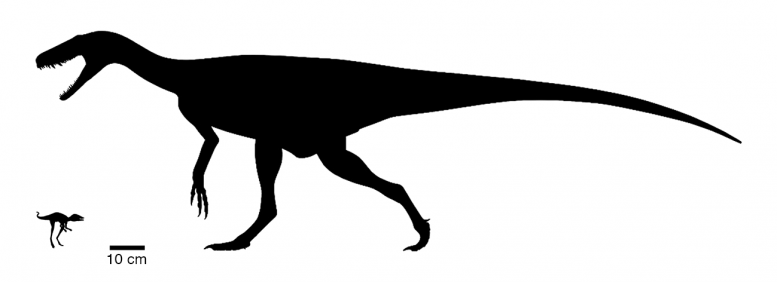

Dinosaurs and flying pterosaurs might be understood for their exceptional size, however a recently explained types from Madagascar that lived around 237 million years ago recommends that they stemmed from exceptionally little forefathers. The fossil reptile, called Kongonaphon kely, or “tiny bug slayer,” would have stood simply 10 centimeters (or about 4 inches) high. The description and analysis of this fossil and its family members, released today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, might assist discuss the origins of flight in pterosaurs, the existence of “fuzz” on the skin of both pterosaurs and dinosaurs, and other concerns about these charming animals.

“There’s a general perception of dinosaurs as being giants,” stated Christian Kammerer, a research study manager in paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and a previous Gerstner Scholar at the American Museum of Natural History. “But this new animal is very close to the divergence of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, and it’s shockingly small.”

Illustration of Kongonaphon kely, a recently explained reptile near the origins of dinosaurs and pterosaurs, in what would have been its natural surroundings in the Triassic (~237 million years ago). Credit: Alex Boersma

Dinosaurs and pterosaurs both come from the group Ornithodira. Their origins, nevertheless, are improperly understood, as couple of specimens from near the root of this family tree have actually been discovered. The fossils of Kongonaphon were found in 1998 in Madagascar by a group of scientists led by American Museum of Natural History Frick Curator of Fossil Mammals John Flynn (who operated at The Field Museum at the time) in close partnership with researchers and trainees at the University of Antananarivo, and task co-leader Andre Wyss, chair and teacher of the University of California-Santa Barbara’s Department of Earth Science and an American Museum of Natural History research study partner.

“This fossil site in southwestern Madagascar from a poorly known time interval globally has produced some amazing fossils, and this tiny specimen was jumbled in among the hundreds we’ve collected from the site over the years,” Flynn stated. “It took some time before we could focus on these bones, but once we did, it was clear we had something unique and worth a closer look. This is a great case for why field discoveries — combined with modern technology to analyze the fossils recovered — is still so important.”

Body size contrast in between the recently found Kongonaphon kely (left) and among the earliest dinosaurs, Herrerasaurus. Credit: Silhouettes from phylopic.org by Scott Hartman (CC BY 3.0) and AMNH/Frank Ippolito.

“Discovery of this tiny relative of dinosaurs and pterosaurs emphasizes the importance of Madagascar’s fossil record for improving knowledge of vertebrate history during times that are poorly known in other places,” stated task co-leader Lovasoa Ranivoharimanana, teacher and director of the vertebrate paleontology lab at the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar. “Over two decades, our collaborative Madagascar-U.S. teams have trained many Malagasy students in paleontological sciences, and discoveries like this helps people in Madagascar and around the world better appreciate the exceptional record of ancient life preserved in the rocks of our country.”

Kongonaphon isn’t the very first little animal understood near the root of the ornithodiran ancestral tree, however formerly, such specimens were thought about “isolated exceptions to the rule,” Kammerer kept in mind. In basic, the clinical idea was that body size stayed comparable amongst the very first archosaurs — the bigger reptile group that consists of birds, crocodilians, non-avian dinosaurs, and pterosaurs — and the earliest ornithodirans, prior to increasing to enormous percentages in the dinosaur family tree.

“Recent discoveries like Kongonaphon have given us a much better understanding of the early evolution of ornithodirans. Analyzing changes in body size throughout archosaur evolution, we found compelling evidence that it decreased sharply early in the history of the dinosaur-pterosaur lineage,” Kammerer stated.

This “miniaturization” occasion suggests that the dinosaur and pterosaur family trees stemmed from exceptionally little forefathers yielding crucial ramifications for their paleobiology. For circumstances, endure the teeth of Kongonaphon recommends it consumed pests. A shift to insectivory, which is related to little body size, might have assisted early ornithodirans make it through by inhabiting a specific niche various from their primarily meat-eating simultaneous family members.

The work likewise recommends that fuzzy skin coverings varying from basic filaments to plumes, understood on both the dinosaur and pterosaur sides of the ornithodiran tree, might have stemmed for thermoregulation in this small-bodied typical forefather. That’s due to the fact that heat retention in little bodies is challenging, and the mid-late Triassic was a time of weather extremes, presumed to have sharp shifts in temperature level in between hot days and cold nights.

###

Reference: “A tiny ornithodiran archosaur from the Triassic of Madagascar and the role of miniaturization in dinosaur and pterosaur ancestry” by Christian F. Kammerer, Sterling J. Nesbitt, John J. Flynn, Lovasoa Ranivoharimanana and André R. Wyss, 6 July 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1916631117

Sterling Nesbitt, an assistant teacher at Virginia Tech and a Museum research study partner and specialist in ornithodiran anatomy, phylogeny, and histological age analyses, is likewise an author on this research study.

This research study was supported, in part, by the National Geographic Society, a Gerstner Scholars Fellowship from the Gerstner Family Foundation and the Richard Gilder Graduate School, the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, and a Meeker Family Fellowship from the Field Museum, with extra assistance from the Ministry of Energy and Mines of Madagascar, the World Wide Fund for Nature (Madagascar), University of Antananarivo, and MICET/ICTE (Madagascar).