The 93-year-old Xerces blue butterfly specimen utilized in this research study. Credit: Field Museum

The Xerces blue butterfly was last seen flapping its rainbowlike periwinkle wings in San Francisco in the early 1940s. It’s normally accepted to be extinct, the very first American insect types ruined by city advancement, however there are sticking around concerns about whether it was truly a types to start with, or simply a sub-population of another typical butterfly. In a brand-new research study in Biology Letters, scientists examined the DNA of a 93-year-old Xerces blue specimen in museum collections, and they discovered that its DNA is distinct enough to benefit being thought about a types. The research study validates that yes, the Xerces blue truly did go extinct, which insect preservation is something we need to take seriously.

“It’s interesting to reaffirm that what people have been thinking for nearly 100 years is true, that this was a species driven to extinction by human activities,” states Felix Grewe, co-director of the Field’s Grainger Bioinformatics Center and the lead author of the Biology Letters paper on the job.

“There was a long-standing question as to whether the Xerces blue butterfly was truly a distinct species or just a population of a very widespread species called the silvery blue that’s found across the entire west coast of North America,” states Corrie Moreau, director of the Cornell University Insect Collections, who started deal with the research study as a scientist at Chicago’s Field Museum. “The widespread silvery blue species has a lot of the same traits. But we have multiple specimens in the Field Museum’s collections, and we have the Pritzker DNA lab and the Grainger Bioinformatics Center that has the capacity to sequence and analyze lots of DNA, so we decided to see if we could finally solve this question.”

A collections drawer of extinct Xerces blue butterflies. Credit: Field Museum

To see if the Xerces blue truly was its own different types, Moreau and her associates relied on pinned butterfly specimens saved in drawers in the Field’s insect collections. Using forceps, she pinched off a small piece of the abdominal area of a butterfly gathered in 1928. “It was nerve-wracking, because you want to protect as much of it as you can,” she remembers. “Taking the first steps and pulling off part of the abdomen was very stressful, but it was also kind of exhilarating to know that we might be able to address a question that has been unanswered for almost 100 years that can’t be answered any other way.”

Once the piece of the butterfly’s body had actually been recovered, the sample went to the Field Museum’s Pritzker DNA Laboratory, where the tissues were treated with chemicals to separate the staying DNA. “DNA is a very stable molecule, it can last a long time after the cells it’s stored in have died,” states Grewe.

Even though DNA is a steady particle, it still deteriorates gradually. However, there’s DNA in every cell, and by comparing several threads of DNA code, researchers can piece together what the initial variation appeared like. “It’s like if you made a bunch of identical structures out of Legos, and then dropped them. The individual structures would be broken, but if you looked at all of them together, you could figure out the shape of the original structure,” states Moreau.

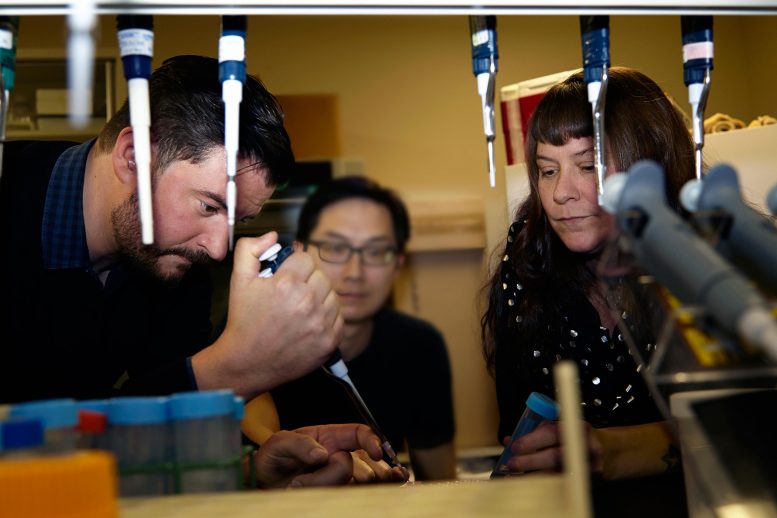

Study authors Felix Grewe and Corrie Moreau operating in the Field Museum’s Pritzker DNA Lab. Credit: Field Museum

Grewe, Moreau, and their associates compared the hereditary series of the Xerces blue butterfly with the DNA of the more prevalent silvery blue butterfly, and they discovered that the Xerces blue’s DNA was various, implying it was a different types.

The research study’s findings have broad-reaching ramifications. “The Xerces blue butterfly is the most iconic insect for conservation because it’s the first insect in North America we know of that humans drove to extinction. There’s an insect conservation society named after it,” states Moreau. “It’s really terrible that we drove something to extinction, but at the same time what we’re saying is, okay, everything we thought does in fact align with the DNA evidence. If we’d found that the Xerces blue wasn’t really an extinct species, it could potentially undermine conservation efforts.”

DNA analysis of extinct types in some cases welcomes concerns of bringing the types back, à la Jurassic Park, however Grewe and Moreau note in their paper that those efforts might be much better invested securing types that still exist. “Before we start putting a lot of effort into resurrection, let’s put that effort into protecting what’s there and learn from our past mistakes,” states Grewe.

Moreau concurs, keeping in mind the immediate requirement to secure pests. “We’re in the middle of what’s being called the insect apocalypse– massive insect declines are being detected all over the world,” states Moreau. “And while not all insects are as charismatic as the Xerces blue butterfly, they have huge implications for how ecosystems function. Many insects are really at the base of what keeps many of these ecosystems healthy. They aerate the soil, which allows the plants to grow, and which then feeds the herbivores, which then feed the carnivores. Every loss of an insect has a massive ripple effect across ecosystems.”

In addition to the research study’s ramifications for preservation, Grewe states that the job showcases the value of museum collections. “When this butterfly was collected 93 years ago, nobody was thinking about sequencing its DNA. That’s why we have to keep collecting, for researchers 100 years in the future.”

Reference: “Museum genomics exposes the Xerces blue butterfly (Glaucopsyche xerces) was an unique types driven to termination” by Felix Grewe, Marcus R. Kronforst, Naomi E. Pierce and Corrie S. Moreau, 21 July 2021, Biology Letters.

DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2021.0123