Illustration by Elham Ataeiazar

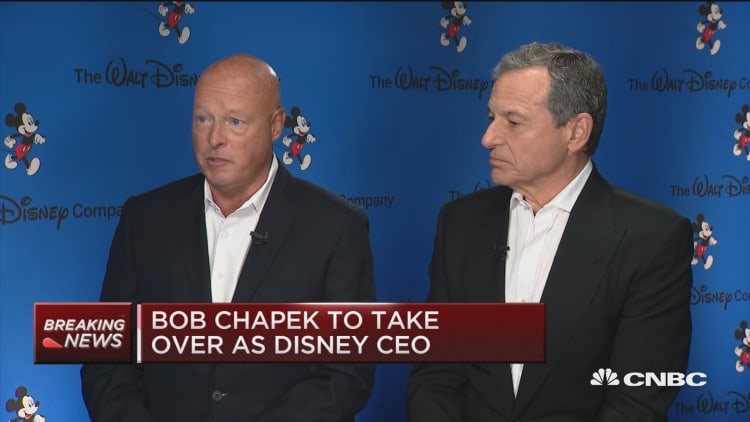

After pushing again his retirement 4 instances, Bob Iger lastly made the leap. On Feb. 25, 2020, he introduced he would step down as Disney’s CEO. His hand-picked successor, Bob Chapek, then Disney’s parks chairman, would take over the day-to-day job of working the corporate, efficient instantly.

As a part of the altering of the guard, the Disney board instructed the brand new CEO ought to take over Iger’s expansive workplace at Disney headquarters in Burbank, California.

There was only one drawback. Iger had little interest in transferring out. He wasn’t actually leaving Disney, anyway. His succession plan allowed him to remain on as govt chairman for 22 months. Chapek would report back to him and the board. Iger would additionally “direct the company’s creative endeavors” — nebulous phrasing suggesting he would retain management of film and TV content material and operations.

There was a sensible cause Iger did not wish to transfer out of his workplace. It had a personal bathe, constructed for former CEO Michael Eisner, and a conceit for shaving. Iger, now 72, constantly awakened round 4:15 a.m. to work out after which bathe on the workplace. On evenings when Iger was heading out for a Disney premiere, award present or profit, he would typically take a second bathe within the workplace.

Iger instructed Chapek that he lived for these “two-shower days,” in line with individuals accustomed to the dialog.

Iger selected Chapek, now 64, as his successor due to Chapek’s integrity and enterprise acumen, not his curiosity in Hollywood socialization. Chapek has the outward company demeanor of a Midwestern businessman — or, as one colleague jokingly put it, “a tuna salad sandwich who sits in front of spreadsheets.” He’s a risk-taker who’s not afraid to upend the established order, however he is not a schmoozer by nature. Whereas Iger holds court docket round his Brentwood mansion — a brief stroll from celebrities, producers, super-agents and different Disney executives — Chapek lives about an hour’s drive from downtown Los Angeles, in Westlake Village. Iger enjoys yachting; Chapek is extra of a power-boating and kayaking form of man.

Both males agreed Chapek would not have a lot want for the workplace bathe; Chapek would as an alternative transfer right into a smaller workplace on the identical flooring.

On the wall of Iger’s workplace toilet hung two posters. The first was a framed collage of newspaper entrance pages and journal covers with pictures of Iger celebrating Disney’s buy of Marvel in 2009. The $Four billion deal was arguably Iger’s shrewdest determination as CEO and probably the greatest media and leisure acquisitions in U.S. company historical past.

The second image spoofed the film poster for the 1975 Clint Eastwood thriller “The Eiger Sanction,” however the picture was of Iger as an alternative of Eastwood, with the title “The Iger Sanction.”

“The Eiger Sanction” is about an murderer who comes out of retirement for one final job.

On Nov. 20, 2022, Bob Iger got here out of retirement to turn into Disney’s CEO as soon as once more. The board had fired Chapek. Within days, Iger fired Chapek’s closest advisors, together with his former chief of workers, Arthur Bochner; his assistant, Jackie Hart; and his de facto second-in-command, Kareem Daniel. In July, Iger prolonged his contract via 2026, the fifth time he has pushed again his departure as CEO.

Chapek confided to a buddy that his tenure at Disney was “about three years of hell,” outlined by one overriding theme: his unrelenting concern that Iger wished his job again.

Iger, in the meantime, has instructed friends and colleagues he returned to Disney to right what he sees as one of many greatest errors of his profession — selecting Chapek.

“When the two people at the top of a company have a dysfunctional relationship, there’s no way that the rest of the company beneath them can be functional,” Iger wrote in his autobiography, “The Ride of a Lifetime.” “It’s like having two parents who fight all the time.”

Iger wasn’t describing his relationship with Chapek — he was recalling his observations dwelling via the meltdown between Eisner and his No. 2, Michael Ovitz, within the 1990s. The pair obtained alongside nice for years, till they grew to become the highest two individuals at Disney. Within 16 months, their relationship had exploded and Ovitz was fired.

But like a son who vows by no means to repeat his father’s errors after which proceeds to do exactly that, Iger’s relationship with Chapek adopted a strikingly comparable sample.

There’s no firm on the planet extra related to storytelling than Disney; its most well-known films are fashionable variations of timeless fables. The story of the Chapek period is timeless in its personal means. It’s a story of how good intentions clashed with hubris and ego to erode probably the most well-known organizations on the planet — a case research in company dysfunction and succession gone fallacious. As Iger and the Disney board resume their seek for a successor, a vital query looms: Have they realized the ethical of the story?

This account relies on conversations with greater than 25 individuals who labored intently with Iger and Chapek at Disney between 2020 and 2022. They declined to be named, because the occasions and conversations had been personal. Many of the small print have by no means been reported.

Through a consultant, Chapek defended his file as Disney CEO in a press release to CNBC.

“Bob is proud of the work he did in the course of his 30-year career at Disney, particularly during his nearly three-year run as CEO, steering the company through the unprecedented challenges of the pandemic, and setting the course for business transformation as he and his team took the disruptive yet necessary steps for business revitalization and long-term growth,” stated a Chapek spokesperson.

Iger declined to remark for this story.

Iger’s succession plan

Iger’s determination to step down as CEO not solely shocked the leisure and media worlds, it took even his shut associates abruptly. Disney’s head of streaming, Kevin Mayer, whom many outsiders had pegged as Iger’s likely replacement, found out minutes before Iger’s public announcement. “I didn’t know that was coming at all,” Mayer told CNBC in 2021.

In February 2020, as Disney’s head of streaming, Kevin Mayer, was in the line of succession for CEO. But Mayer, seen here on Sept. 29, 2022, and colleagues were stunned when Iger announced Bob Chapek would replace Iger immediately.

Bryan van der Beek | Bloomberg | Getty Images

But Iger figured the timing was right. He was getting close to 70 and he’d been CEO for almost 15 years. The company’s recently launched streaming service, Disney+, was an instant success. And Iger was convinced Chapek was the right caretaker to continue his legacy.

Chapek grew up in Hammond, Indiana, “the son of a World War II veteran and a working mother,” as he has described it. His family took annual trips to Walt Disney World when he was young, seeding his genuine love for the company’s theme parks. He studied microbiology at Indiana University and got his MBA from Michigan State University. He joined Disney in 1993 and by 2015 had risen to become chairman of the parks division.

For more than two decades, Chapek earned Iger’s respect as a shrewd cost-cutter and a low-drama manager. Iger especially valued Chapek for his integrity and operational expertise. At each of the divisions Chapek led at Disney — home video, consumer products and parks — profit and revenue soared under his watch. He also benefited from some good timing, running the home video division when Disney animation hits such as “The Little Mermaid,” “Aladdin” and “Beauty and the Beast” were first sold on VHS and piloting consumer products just as “Frozen” launched.

Chapek cemented his reputation with Iger and the board during the construction of Shanghai Disney, the $5.5 billion theme park that opened in 2016 after months of delays. Iger and Chapek traveled to Shanghai, China, together more than 10 times as Chapek got the cost overruns and construction headaches under control. His success helped Iger move on from former Chief Operating Officer Tom Staggs, who was then in line to take the CEO job after Iger. Staggs left the company just before Shanghai Disney finally opened.

Tom Staggs, then Disney COO, announces the Iron Man Experience planned for Hong Kong Disneyland in 2016. Staggs had been promoted to the job specifically to be Iger’s heir apparent.

Walt Disney Parks and Resorts

It was Iger’s experience with Staggs — who didn’t secure Disney’s top job after being promoted to COO specifically to be Iger’s heir apparent — that made Iger decide Chapek should start as CEO immediately. He told board members he didn’t think Chapek needed to audition for the role.

Years later, Iger would tell others he mistook Chapek’s stellar operational track record for leadership skills.

This was a striking admission for Iger, who prides himself on his emotional intelligence. He is charming with co-workers and at ease with celebrities — a Hollywood star in his own right. These traits paid dividends over the years. He convinced Steve Jobs to sell him Pixar, cajoled Ike Perlmutter into selling him Marvel, and persuaded George Lucas to sell him “Star Wars” and its bounty of associated intellectual property. In 2017, he struck a deal with Rupert Murdoch to buy most of Fox.

Some Disney executives have privately speculated that Iger chose Chapek because he wouldn’t rival him in either charisma or celebrity — or, more cynically, because he was unlikely to eclipse Iger’s glittering record at the company.

What’s clear is Iger didn’t know Chapek as well as he should have. On a day-to-day basis, Iger worked far more closely with Mayer and Staggs. Iger doesn’t mention Chapek once in his 2019 autobiography outside of the prologue — even though by then Chapek was at least tentatively in line to be Iger’s preferred successor. For comparison, Iger spends more than five pages of his 236-page book discussing “Twin Peaks.”

The entire process of naming a successor was bumpy. For a start, Iger kept delaying his retirement: In 2013, 2014 and then twice in 2017, he renewed his contract after saying he intended to walk away.

In 2017, according to people familiar with the matter, Iger first told Chapek he was in the running to be his potential successor. The vetting process for CEO would begin with Chapek flying across the country to meet one-on-one with board members — not unlike contestants’ hometown dates on Disney’s hit reality show “The Bachelor.” Iger had gone through a similar process, taking 15 meetings with directors before securing the CEO position in 2005.

But Chapek never did the meetings. Iger agreed to buy the majority of Fox’s assets in a $71 billion deal and renewed his contract as a condition of the purchase, pushing back any talk of succession.

In January 2020, Iger told Chapek the plan was back on. This time, Iger told him that instead of the one-on-one board interviews, Disney’s lead independent director, Susan Arnold, would be in touch. Days later, Arnold delivered the news to Chapek over lunch at The Rotunda, Disney’s executive dining room. She and Iger had both recommended Chapek for the job, and the board had approved. Chapek sat on the secret for six weeks before the public announcement.

Peter Rice, seen here on May 3, 2017, was head of Disney’s TV entertainment business in 2020. He was one of several executives passed over for the CEO job in favor of Chapek.

David Paul Morris | Bloomberg | Getty Images

In choosing Chapek, Iger and the directors had passed over Mayer and Peter Rice, then head of Disney’s TV entertainment business. The board felt the leadership styles of both men were too brash, according to people familiar with some of the directors’ thinking. Also, Mayer had never run a business of scale, and Rice had joined the company from Fox less than two years earlier.

However, Iger never consulted anyone who worked directly for Chapek in the runup to naming him CEO, according to people familiar with the matter.

He had pegged Chapek as someone who would accept his somewhat unusual succession plan, in which Chapek would serve both as CEO and CEO-in-training while Iger remained his boss and ran “creative endeavors” for 22 months as executive chairman.

“Any of the big creative decisions that have to be made, I fully intend for Bob [Chapek] to be at my side,” Iger told CNBC’s Julia Boorstin on the day of the announcement. “What this is about, really, is, we believe, a really good succession process and a really smart transition process.”

WATCH: Bob Iger steps down as Disney CEO and announces Bob Chapek will take his place

Iger needed full buy-in from the board for his plan, but that did not prove difficult. Over the past 15 years he had become the gold standard of legacy media and entertainment CEOs. From the time he’d taken over at Disney to the end of February 2020, Disney’s share price increased about 420%, far outpacing the S&P 500 index, which gained about 150%.

By 2019, Iger had personally selected every member of the board, which is surprisingly lacking in media and entertainment experience. Iger is personally close with several of them, including Nike Executive Chairman Mark Parker and General Motors CEO Mary Barra. In addition, the wife of another director, Michael Froman, then vice chairman of Mastercard and now president of the Council on Foreign Relations, had been housemates with Iger’s wife, Willow Bay, at the University of Pennsylvania.

It was from Parker that Iger got the idea for his succession plan, according to people familiar with the matter. In October 2019, Parker, who was then CEO of Nike, announced he would remain as executive chairman of Nike while passing the torch to John Donahoe.

That structure also happened to be nearly identical to one that Iger’s predecessor Eisner tried and failed to secure for himself. In 2004, Eisner floated a plan in which he would step down but remain as chairman, while Iger would take over as CEO.

But unlike Iger, Eisner had lost his grip on the board. Directors Roy Disney, a nephew of Walt Disney, and Stanley Gold resigned their seats and in a blistering letter objected to the notion of Eisner remaining as chairman. “[His] ‘succession plan’ is for a company led by Michael Eisner and his obedient lieutenant, Bob Iger, to be handed over to … Michael Eisner and Bob Iger,” they wrote. “Any arrangement that permits Mr. Eisner to remain as Chairman after relinquishing his position as CEO is contrary to best governance practices.”

Michael Eisner, former Disney chairman and CEO, is seen here on July 11, 2023. In 2020, Iger came up with a succession structure that was nearly identical to one his predecessor Eisner tried and failed to secure for himself in 2004.

David A. Grogan | CNBC

Eisner relinquished his chairman role in March 2004 after 43% of Disney shareholders withheld their votes to reelect him to the board the year before. He resigned as CEO in September 2005. Iger assumed leadership of the company without anyone hovering over his shoulder. This allowed him to move quickly on decisions that Eisner might not have agreed with, such as buying Pixar. Iger describes the acquisition process at length in his autobiography.

Chapek wouldn’t have nearly the same degree of freedom.

Big Bob and Little Bob

In “The Ride of a Lifetime,” Iger recalls watching Eisner leave the Disney lot on his last day at the company: “It’s one of those moments, I imagine, when it’s hard to know who exactly you are without this attachment and title and role that has defined you for so long.”

Just weeks after Iger announced his departure, Chapek began to wonder if Iger had regrets, according to people familiar with his thinking. Equally soon, Iger started to think he’d made a mistake.

At first, the signals were tiny. When Iger announced his departure to staff on Disney’s Burbank studio lot, he jokingly called himself “Big Bob” and Chapek “Little Bob,” a light reminder to employees about who was still the boss.

On March 10, 2020, about two weeks after the handoff, Chapek, Iger, Chief Financial Officer Christine McCarthy and a small handful of other Disney executives flew from Los Angeles to Raleigh, North Carolina, for Disney’s annual meeting.

At the front of the plane, Iger and Chapek were going over logistics and fretting about coronavirus. Iger caught Chapek off guard with some news. Chapek, not Iger, would lead the question-and-answer portion of the meeting, an annual ritual Iger called “stump the CEO.”

During his 27 years at the company, Chapek had only attended one annual meeting — as a guest in the audience.

Chapek, then Disney CEO, speaks during a media preview of the D23 Expo, on Aug. 22, 2019.

Patrick T. Fallon | Bloomberg via Getty Images

Since Chapek’s background at Disney had been in parks, consumer products and distribution, he knew little about the inner workings of ABC, ESPN or the movie studio. He’d been given a large binder of background material by the investor relations team, but now he had to be ready to answer questions on any topic, which could range from Disney’s stance on the environment to the future of ABC News.

After a couple of hours of general preparation, Chapek retreated to a private area in the back of the plane and closed the door to study. Iger was perplexed and expressed his confusion to McCarthy. He assumed the men would run through possible questions and answers throughout the flight. Iger walked to the back of the plane to see if Chapek needed help preparing.

“Isn’t it all in here?” Chapek asked, holding up the binder, according to a person on the plane.

The basics, yes; but not the nuances, Iger replied. Chapek, who prefers to learn by reading and memorizing material — and thought he’d already spent the first hour or two prepping with Iger — said he’d rather stay in back and study. (The first question Chapek would receive was whether he thought there was bias within ABC News — a topic about which he knew little but had prepared for on the plane, according to people familiar with the matter.)

Iger would later relay this fleeting exchange to friends as one of the first moments it occurred to him that he may have made a mistake. He had thought he was handing off the company to a collaborative leader who would work with him side by side for the next 22 months. Iger began to worry about whether Chapek had plans of his own.

Chapek’s first concerns that Iger might be having regrets came during the next day’s flight back to Los Angeles, after a brief stop in Orlando for a Disney town hall.

Coronavirus fears had billowed into a full-fledged panic. Chapek stayed up front with McCarthy and Iger, who got on a call with California Gov. Gavin Newsom to discuss whether Disneyland should be shut down; it would be by the morning of March 14.

Christine McCarthy, seen here on April 29, 2019, was Disney’s chief financial officer. As Iger’s departure from Disney prompted other executives to leave, Chapek worked overtime to make sure he retained the veteran McCarthy.

Michael Kovac | Getty Images

At some point, amid the chaos, McCarthy suggested to Chapek that they do their first weekly CEO-CFO meeting. They were around the third agenda point when Iger snapped. It was disrespectful to conduct this meeting right in front of him, he complained curtly, according to a person familiar with the exchange.

It was rare for Iger to show Chapek a side of himself that wasn’t “Disney nice” — the term many executives use for a corporate culture that emphasizes kind and respectful interactions. Chapek and McCarthy quietly finished their meeting, but Chapek told others after the flight he left with the distinct impression that Iger was having second thoughts about relinquishing the job he’d held for 15 years.

These dueling perceptions that manifested themselves on that March round-trip flight — Chapek as bumbling and isolated; Iger as unwilling to give up control — would define the next 2½ years.

Relationship breakdown

Just days later, the two men had their first strategic disagreement. Chapek wanted to furlough about 100,000 parks employees after Disney World closed its gates. Iger advocated waiting for the government’s Covid-19 relief act to kick in so the furloughed employees would have some government money to hold them over. Iger called then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, both Democrats, to ask them how close the U.S. government was to passing the bill. Ten days, they told him. Though it wasn’t a creative issue, Iger overruled Chapek. Disney didn’t furlough employees until April.

Around the same time, New York Times media columnist Ben Smith published a story about the pandemic’s disastrous impact on Disney. After “a few weeks of letting Mr. Chapek take charge,” Smith wrote, Iger had “effectively returned to running the company.” Iger didn’t deny this. “A crisis of this magnitude, and its impact on Disney, would necessarily result in my actively helping Bob and the company contend with it, particularly since I ran the company for 15 years!” Iger said in an email to Smith.

Chapek was furious. He called Iger and told him he didn’t need a savior, dropping a carefully placed expletive or two, according to people with knowledge of the call. It was the first time in more than 20 years that Chapek and Iger had had a major argument. Iger would tell people no colleague had ever spoken to him like that before in his life.

Chapek also complained to the Disney board about the story, demanding to be given a seat immediately; Disney had promised him one but had not set a date. Chapek did not want Iger and the board talking about him or his job status while he wasn’t there, according to people familiar with his thinking. Three days after Smith’s story ran, Disney complied. Arnold privately had a strongly worded conversation with Iger about setting him up for success rather than undermining him, according to people familiar with the conversation.

Arnold declined to comment for this story.

The relationship only deteriorated from there. Iger began privately grumbling that Chapek wasn’t involving him in company decisions. He told colleagues that he felt like he was on a bus that the other passengers wanted him to drive but he couldn’t reach the steering wheel. He began to understand that Chapek was not going to be an “obedient lieutenant,” as Roy Disney and Stanley Gold had once theorized Iger, himself, would be as Eisner’s chosen CEO.

At the end of a June board meeting, conducted via Zoom, Disney directors asked Iger — but not Chapek — to stay on the call for a customary “executive session.” According to people familiar with this conversation, Iger told the board his relationship with Chapek had soured and that Chapek wasn’t exhibiting proper leadership qualities. The pandemic was shaking Disney to its foundations, and Iger believed Chapek should be working more closely with the man who had run the company for the last 15 years.

Bob Iger, Disney CEO, during a CNBC interview, Feb. 9, 2023.

Randy Shropshire | CNBC

After Iger left the call, the board brought back Chapek and asked him if employees were aware of how bad things had gotten between the two men. Chapek said he didn’t think so, but he knew Iger had been complaining about him to Disney confidants and Hollywood executives and agents.

Iger and Chapek never participated in a face-to-face mediation about their working relationship. The board never demanded it. Privately, Arnold counseled Chapek to be patient, something she’d continue to do for months to come in a series of coaching sessions. Let Iger run creative, she said. In 18 months, Chapek would have control of everything. Until then, don’t engage in turf wars.

In less than four months, Iger’s plan for a managed succession had gone up in flames.

Dividing the company

When Chapek took over Disney, it was clear that Wall Street cared more about its streaming results than any other division of the business. Iger had already begun to reposition the company accordingly: “We’re all in,” he said when he unveiled Disney+ in April 2019. It added more than 10 million paying subscribers in 24 hours.

However, Chapek saw two major problems with the streaming operation. First, he believed there were too many people making decisions about what content was slated for Disney+. Iger and Mayer had tasked this responsibility to Agnes Chu, senior vice president of content, and Ricky Strauss, president of content and marketing for Disney+. Both Chu and Strauss have since left Disney.

Others wanted a say, including Mayer, Chu and Strauss’s boss, as well as Marvel Studios President Kevin Feige, Lucasfilm head Kathleen Kennedy, and the heads of Walt Disney Television and Walt Disney Studios. Mayer told Chapek the structure was messy and needed fixing.

Chapek brought a business school mentality to this challenge, which naturally rubbed creative executives the wrong way. He often cited the concept of ARCI — which stands for “accountable, responsible, consulted and informed” — as a framework for ensuring clear decision-making structures. Chapek would often say, “Who’s got the A?” — referring to accountability. With streaming, the answer wasn’t clear.

Second, Chapek understood that streamed movies were still seen as less prestigious than those with a traditional theatrical release. The chair of Walt Disney Studios, Alan Bergman, and his direct reports were reluctant to give projected hits to Disney+ or Hulu. Actors and directors overwhelmingly still wanted a box-office release. Even during Covid, Disney didn’t abandon exclusive theatrical releases, unlike WarnerMedia, which put each of its 2021 films on HBO Max and in cinemas on the same dates.

Alan Bergman, chairman of Walt Disney Studios, at the D23 Expo, Sept. 10, 2022. Bergman lost some decision-making power under Chapek.

The Walt Disney Company via Getty Images

But box-office returns weren’t driving investor sentiment — streaming was. And during the early months of Covid, Disney had limited inventory because production on new TV series and movies had ground to a halt. Chapek wanted to put premium programming on Disney+ as soon as possible.

His idea was to implement a “make-sell” model, a phrase Chapek borrowed from Iger, who had discussed it with former YouTube executive Bob Kyncl in 2018. The idea was to create a clear division between people who make shows and movies and people who sell them. Studio heads and content division leaders would still choose which projects to greenlight, but someone else would have the authority to bring needle-moving content to Disney+ or Hulu.

Companies such as Netflix, Amazon and Apple also separate distribution divisions from content creation, and Chapek hoped that adopting a similar structure would move Disney away from its legacy media habits. Investors valued Netflix far higher than legacy media because of its growth profile; if Chapek could get investors to view Disney as a technology company, they might reward him with a share price multiple bump.

To this end, Chapek created a new group called Disney Media and Entertainment Distribution, or DMED. To lead the division, he chose Kareem Daniel, then a 46-year-old executive who had worked closely with Chapek for years, first as a Stanford MBA intern in home entertainment and later in both distribution and theme parks. The reorganization gave Daniel — and Chapek — veto power over movie and TV show budgets.

Chapek had a series of meetings with Iger to discuss the restructure, including conversations in Iger’s Brentwood house and walks around the neighborhood. Despite the unaddressed tensions between the two, the conversations were cordial, according to people familiar with their interactions.

Iger didn’t try to stop Chapek’s plan, but he also didn’t give it his full endorsement. His opaque communication style frequently confused Chapek, according to colleagues. Chapek couldn’t tell whether Iger’s questions were a passive-aggressive way to signal disapproval or a genuine attempt to get more information.

Inside Disney, many executives saw the reorganization as a way for Chapek to shift the power balance away from Iger’s base — TV and movie executives. Chapek had long felt that Disney’s culture, under both Iger and Eisner, treated non-creative executives like him as second-class citizens, according to people familiar with his thinking.

But Daniel rankled many company leaders, who thought he lacked the industry experience or humility for the job. Daniel was known for his intelligence, but he was prone to harshly shooting down opinions with which he disagreed, according to colleagues who worked with him. Chapek tried, unsuccessfully, to coach him to be more “Disney nice.”

Daniel declined to comment for this story.

Kareem Daniel was hired by Chapek to lead a new group called Disney Media and Entertainment Distribution. The reorganization gave Daniel — and Chapek — veto power over movie and TV show budgets.

Source: Business Wire

As agents and major Hollywood players realized Daniel was Disney’s new power broker, his inexperience in the entertainment world surfaced in ways that embarrassed some colleagues. He’d enlist several members of his communications team to help him navigate the red carpet at premieres, causing some executives to chuckle about his self-importance. His team would also prepare documents advising him how to act during these events, complete with talking points for impromptu conversations with celebrities, press or producers on the carpet. The DMED communications division eventually ballooned to more than 100 employees, which some on the team felt was wildly excessive. Given DMED’s importance to the future of the company, Chapek didn’t intercede.

Still, some of Daniel’s colleagues felt veteran Disney executives were being unfairly dismissive of him. It was Daniel’s responsibility to set cost controls, so irritating studio executives was practically a requirement of his job. Chapek adjudicated dozens of conflicts between Daniel and Bergman, according to people familiar with the matter. Both men got used to walking away frustrated.

Bergman declined to comment.

Directors, producers and actors panned the reorganization. In a town where relationships matter, they didn’t know Daniel. They wanted clarity on whether their movie would go straight to streaming or get a theatrical release, and their usual contacts on the creative side could no longer give them straight answers.

When it came to TV, there was less resistance to the organizational changes, because streaming wasn’t associated with inferior quality. While creative executives were cut off from important data they used to judge the performance of their shows, in an era of declining broadcast ratings, landing on a streaming service often increased the total audience and extended the lifetime of TV series.

One exception was ESPN. Rights deals are the sports network’s lifeblood, and ESPN executives were used to hammering them out directly with leagues. After the reorganization, ESPN executives lost their budget power and gained layers of bureaucracy.

ESPN Chairman James Pitaro, seen here on July 25, 2023, contemplated leaving the company after Chapek’s reorganization.

Jesse Grant | CNBC

Chapek was trying to rearrange the company at a time when nearly all employees were working from home. Virtual meetings ballooned in size. Conversations became unwieldy. Junior executives from Daniel’s distribution team, who were involved in meetings because ESPN+ was being sold alongside Hulu and Disney+, asked questions of league officials that exposed their lack of business knowledge.

ESPN Chairman Jimmy Pitaro was so demoralized he contemplated leaving the company, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Pitaro declined to comment.

Awkward situation

Throughout all this, executives who had lost power under the new structure were frantically complaining to Iger, who told them he didn’t agree with the reorganization — an assessment Chapek heard only indirectly — but that there was little he could do.

Many veteran Disney creative executives viewed the reorganization as an example of poor decision-making. Chapek loyalists saw it as a necessary change to modernize Disney, which they felt was being sabotaged by petulant TV and movie executives, with Iger’s tacit backing, according to people who were directly involved in the reorganization.

Around this time, in late 2020 and into 2021, Disney executives throughout the company started to feel increasingly awkward about the Iger-Chapek relationship. McCarthy warned Chapek that Iger’s criticism was reaching an increasingly wide audience.

McCarthy declined to comment for this story.

Most tried to ignore the rift and just do what they were told.

Zenia Mucha, who had been Disney’s head of communications since 2002, before Iger started as CEO, took a more active approach. Reminding Chapek of his predecessor’s legacy and stature, she urged him to portray a united front with Iger.

But Chapek didn’t trust Mucha, who was so close to Iger that some at Disney referred to her as his second in command. Chapek felt she was Iger’s communications advocate and not his. Others close to Chapek felt Mucha wasn’t championing him as much as a communications head should be celebrating a new CEO. Mucha argued the country was being ravaged by coronavirus and it wasn’t the right time for puff pieces in Hollywood trade magazines, according to people familiar with the matter.

Zenia Mucha, then Disney’s head of communications, left, seen here with Barbara Walters on April 23, 2012, urged Chapek to portray a united front with Iger. But Chapek didn’t trust Mucha, who was so close to Iger that some at Disney referred to her as his second in command.

Charles Eshelman | Filmmagic | Getty Images

Chapek felt he couldn’t fire Mucha with Iger still lurking as chairman, according to people familiar with the matter. On the advice of the board, who agreed that Chapek needed communications help, Chapek began soliciting advice from external communications firm Brunswick Group in early 2021 — without informing Mucha. He hoped Brunswick could improve his image in Hollywood, where he was growing increasingly unpopular with frustrated content creators and agents.

Mucha declined to comment.

The Scarlett Johansson controversy

The first half of 2021 was good for both Disney and Chapek. The share price was rising. Disney+ topped 100 million subscribers in March, blowing away Netflix’s gains throughout the year. The world was getting vaccinated and returning to theme parks.

During a June board meeting in Hawaii at Disney’s Aulani resort, members heaped praise on Chapek, according to people familiar with the proceedings. This time, instead of asking Iger to stick around at the end for a private executive session, they asked Chapek. It was a small gesture, but one Chapek interpreted as the board viewing him as the true leader of the company, according to people familiar with his mindset at the time.

Chapek told colleagues he was finally feeling more comfortable in the job. More specifically, Chapek felt as though Iger had lost his path to return.

In hindsight, it may have been the peak of Chapek’s tenure. Only a month later, Chapek found himself back on shaky ground.

In March, Chapek and Daniel had made the decision to launch “Black Widow” — a Marvel movie starring Scarlett Johansson — for a premium additional price on Disney+ and in theaters on the same day, July 9, 2021.

Scarlett Johansson and Florence Pugh star as Natasha and Yelena in Marvel’s “Black Widow.” Johansson sued Disney for breach of contract after it released the film in theaters and streaming on the same day.

Disney

There was one hitch: Johansson’s contract stipulated that her compensation was based on an exclusive theatrical release for up to four months. Since her contract was negotiated before Covid, this type of issue hadn’t arisen before. Her agent, CAA partner Bryan Lourd, spent months negotiating with Disney executives throughout the organization, warning Bergman and Chapek that Johansson would sue for remuneration if they proceeded with their plan, according to people familiar with the discussions.

Chapek viewed Johansson’s contract as a creative issue and therefore Iger’s territory. Iger had a long relationship with Lourd and knew Johansson. This was his arena.

Iger, however, wasn’t involved in any of the conversations with Lourd, who thought Iger would have quickly resolved the situation given the value he historically placed on creative relationships, according to people familiar with the matter.

Lourd declined to comment.

If Chapek wanted to be CEO, he should be CEO, Iger reasoned. To Iger, this was a clear business matter — a contract dispute — and not a “creative endeavor,” according to people familiar with his thinking.

By this time, Chapek and Iger were barely speaking to each other.

In July, after multiple warnings from Lourd, Johansson sued. Disney’s lawyers walked through the company’s options in a virtual meeting attended by about 20 executives, including Iger and Chapek. Iger didn’t speak, but he felt the meeting was “amateur hour” — a meeting “run by children” — with far too many people weighing in on how the company should respond, according to a person familiar with his thoughts.

Iger and Chapek both signed off on an aggressive public statement that accused Johansson of “a callous disregard for the horrific and prolonged global effects of the Covid-19 pandemic” and revealed her $20 million salary for the film. The clear implication was that she was only seeking more money out of greed.

Mucha argued Disney needed to have a forceful response because the lawsuit specifically named Iger and Chapek as financial beneficiaries from a stronger Disney+.

Yet, both Iger and Chapek disagreed with the tone of the statement, according to people familiar with the matter. Neither one stopped its release because each believed the other should be in charge.

Iger called Chapek and told him he should issue a public apology, according to people familiar with the call. Chapek refused, said the people. Iger never even considered apologizing, according to people familiar with his thinking.

Hollywood talent and agents largely blamed Chapek for the statement. Chapek suspected Mucha was pushing this narrative to the press. To defend himself, Chapek solicited other members of the communications team to help him call reporters, without informing Mucha.

Disney settled the lawsuit in October 2021.

Bob Iger speaks during a CNBC interview at Disneyland in Anaheim, California, Dec. 16, 2021.

David A. Grogan | CNBC

That November, Iger threw himself a goodbye party at his Brentwood house. After 26 years, he was finally leaving Disney. He invited about 70 guests, including director Steven Spielberg, famed sports broadcaster Al Michaels, ABC broadcasting anchors David Muir, Robin Roberts and Michael Strahan, and many former and present Disney leaders.

Iger reluctantly invited Chapek. When he found out Chapek had a speaking engagement at Walt Disney World set for that day, he was relieved, according to people familiar with his mindset at the time. He didn’t want Chapek to attend — and the feeling was mutual. Chapek’s first impulse was to decline. But he knew it would look terrible if he didn’t attend, so he canceled his plans in Orlando.

At the party, the tension between the two was palpable. Iger sat next to Spielberg, while Chapek sat far away at the opposite table, visibly miserable. It did not escape attendees that Iger thanked dozens of people in his speech — but not Chapek. It was humiliating, but Chapek told friends he felt relieved the tension was out in the open.

With Iger gone, Chapek could finally run Disney his way. He moved into Iger’s larger office, the one with the private bathroom — but he never actually used the shower, as Iger predicted, according to people familiar with the matter.

Chapek turned to some executive housekeeping that Iger’s presence had prevented. He combined government relations with media communications, naming former BP corporate affairs boss and onetime Defense Department press secretary Geoff Morrell as chief of corporate affairs. That decision effectively forced out Mucha, as well as general counsel Alan Braverman, whom Chapek viewed as a diehard Iger loyalist.

Other veteran executives left to coincide with Iger’s departure. They included Alan Horn, Disney’s chief creative officer and chairman of Walt Disney Studios from 2012 to 2020, and Jayne Parker, the head of human resources who had been at Disney for more than 30 years. Chapek also fired Rice, the well-respected head of TV, in June, telling him that he wasn’t a cultural fit. Rice had been at Disney for about three years after coming to the company via Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox.

To combat the outflow of institutional knowledge, Chapek worked overtime to make sure he retained McCarthy, the CFO. McCarthy, who had joined Disney in 2000 and who was in her late 60s, was a master of internal politics and had close ties to the board, according to colleagues. Chapek jokingly offered McCarthy a lifetime contract after he found out she had bought a house in Montana, a sign she was thinking about retiring, according to people familiar with the matter.

By this point, Chapek’s inner circle had shrunk to a handful of senior executives. He didn’t trust most of the existing leadership, largely because of their ties to Iger, and primarily relied on Daniel, Bochner (later replaced by Claire Lee), Chief Human Resources Officer Paul Richardson, McCarthy and the new head of parks, Josh D’Amaro.

Chapek did feel he had an ally in Arnold, who had become the new board chair, according to people familiar with his thoughts. Arnold represented the post-Iger power center of Disney, and she was now also Chapek’s boss. It wasn’t long, though, before she found herself in the center of a firestorm.

A fight in Florida

A little more than a month into Chapek’s tenure without Iger at the company, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, introduced the Parental Rights in Education Act — which critics called the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. The legislation would prohibit “classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity.”

Disney is one of the largest taxpayers and employers in Florida, and Chapek and Morrell were soon fielding media inquiries about the company’s stance on the matter. And employees — particularly animators at Pixar and Disney Animation — wanted to know how the company planned to react.

Iger tweeted his thoughts. “If passed, this bill will put vulnerable, young LGBTQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer] people in jeopardy,” he wrote.

During Iger’s tenure as CEO and chairman, he had freely pontificated about an array of causes, together with local weather change, variety and abortion. In a collection of digital conferences after the killing of George Floyd, Iger had instructed Disney staff that making their voices heard was one of the simplest ways to result in change, in line with individuals on the calls.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican presidential candidate, speaks in Rye, New Hampshire, July 30, 2023. Chapek determined to not take a public stance on DeSantis’ laws referred to as “Don’t Say Gay,” prompting backlash from Disney staff.

Reba Saldanha | Reuters

Chapek wished to chart a unique path. Weeks earlier than DeSantis launched his deliberate laws, Morrell had outlined a brand new communications technique to the board. He wished Disney to remain out of political skirmishes totally and as an alternative sign its values via “three Cs”: content material, tradition and group organizations supported by Disney.

Chapek and Morrell had assumed they’d have months to elucidate their technique internally. But Iger’s tweet dialed up the strain on Chapek to say one thing.

On March 7, 2022, Chapek and Morrell put their new public relations technique into motion. They penned a memo to all workers, authorised by the board. It defined that the corporate wouldn’t take a public stance on the invoice.

Arnold, who’s overtly lesbian, signed off on the assertion however instructed Chapek that Disney also needs to signal a public letter by the Human Rights Campaign, or HRC. The letter, which had already existed for months, compiled a listing of U.S. firms generically “united in opposing the wave of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation.” Chapek meant to signal the HRC letter however did not wish to undercut the message of the preliminary assertion. Morrell and Chapek agreed that doing so would battle with the corporate’s new technique of staying away from exterior conflicts, in line with individuals accustomed to their considering.

In the memo to workers, Chapek wrote: “Corporate statements do very little to change outcomes or minds. Instead, they are often weaponized by one side or the other to further divide and inflame. Simply put, they can be counterproductive and undermine more effective ways to achieve change.”

Disney worker Nicholas Maldonado holds an indication exterior Walt Disney World on March 22, 2022, throughout a companywide walkout to protest Disney’s response to the “Don’t Say Gay” invoice.

Octavio Jones | Getty Images News | Getty Images

The blowback was swift. Employees chastised Chapek with hashtags corresponding to #Disneydobetter and #Disneysaygay. But Chapek and Morrell had been satisfied this was the best factor for the corporate. They did not need Disney in a tradition conflict with DeSantis, with whom Chapek had a stable relationship on the time.

They had been additionally fascinated about China, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter. Disney’s “Avengers: Endgame” made an astounding $614 million on the Chinese field workplace in 2019. Disney additionally owns billion-dollar theme parks in Shanghai and Hong Kong. Chapek and Morrell believed it could be far simpler to keep away from battle with the Chinese authorities if Disney embraced a coverage of not taking stances on social and political points.

Arnold instructed Chapek she’d been bombarded by livid feedback from the LGBTQ group and sensed Disney’s model was in danger. Chapek must stroll again the assertion for the great of the corporate, she stated.

Red-faced with anger, Chapek laid into his communications staff, telling them he regretted placing out the assertion if the board refused to again him, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter. But Chapek was hardly working from a place of power. He did not but have an extension to his contract, which was set to run out in February 2023. Thumbing his nostril at Arnold would hardly be clever.

Chapek scrambled for a brand new public response. He walked again his assertion at Disney’s annual assembly, which occurred to be simply two days later. “I understand our original approach, no matter how well intended, didn’t quite get the job done,” Chapek stated. “But we’re committed to support the community going forward.”

Morrell, who had already championed having group organizations lead the cost for Disney’s social advocacy, instructed the corporate donate cash to an LGBTQ trigger — however he wasn’t positive which one. He and Chapek landed on giving about $5 million to the HRC and signing the general public letter. The HRC rejected the donation.

Disney’s lead impartial director Susan Arnold instructed Chapek he wanted to formally apologize to Disney staff for not taking a public stance towards Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” invoice.

Source: Disney

Still unhappy, Arnold instructed Chapek he wanted to formally apologize — particularly to Disney staff. “You needed me to be a stronger ally in the fight for equal rights and I let you down,” Chapek wrote in a March 11 assertion to staff that they penned collectively. “I am sorry.”

The labored apology solely did a lot. On March 22, lots of of Disney staff held a walkout to protest Chapek’s dealing with of the state of affairs. Chapek agreed to go on a listening tour all through the corporate to reply any questions and tackle considerations.

In a late March interview with CNN’s Chris Wallace, Iger had some veiled phrases for Chapek. “When you’re dealing with right and wrong, or when you’re dealing with something that does have a profound effect on your business, then I just think you have to do what is right and not worry about the potential backlash to it,” Iger stated.

This was the second important communications gaffe pinned on Chapek in lower than a yr. Chapek fired Morrell in April, abandoning his plan to merge communications with authorities affairs. He changed him with Kristina Schake, who co-founded the American Foundation for Equal Rights, a company that led a authorized problem to revive marriage equality in California.

Chapek’s repute throughout the firm had been significantly broken. As a brand new CEO, he did not have the clout or inner respect to simply bounce again from missteps.

An apt juxtaposition is how Iger responded in 2019 after making an unintended insensitive joke at a senior administration retreat in Orlando.

At the biannual multiday gathering, executives participated in athletic occasions corresponding to softball, horseback driving, yoga and bowling. The video games had been incessantly high-spirited. Former ESPN head John Skipper as soon as ruptured his Achilles tendon enjoying volleyball at one of many occasions and was taken to the hospital. In truth, that yr, Kareem Daniel hit a bit of dribbler down the primary bottom line and ran full velocity to beat out a success. Chapek was enjoying first base and charged towards the ball. Daniel steamrolled over Chapek, knocking the wind out of him, in line with individuals who had been there.

About an hour after the conclusion of the athletic exercise, with executives nonetheless buzzing over Daniel smashing into his boss, Iger offered the “Tinkerbells” — spoof awards accompanied by some gentle roasting of the recipient. Iger confirmed a photograph of Latondra Newton, then Disney’s chief variety officer, who’s Black, driving a white horse. Iger quipped, “Now that’s a horse of a different color,” a colloquial phrase used to check two very various things. He added that Newton was all the time working, selecting to experience the white horse to give attention to variety when all the opposite horses had been brown.

There was a collective groan. Iger shortly realized he’d unintentionally introduced the topic of race into a lightweight awards dinner. After the ceremony, he discovered Newton and apologized. He spoke together with her for about an hour the subsequent day, too, and known as nearly 20 Black executives who had been within the room that day to apologize. Iger known as Arnold, too, to elucidate what occurred.

“Bob apologized to me afterwards and we had an honest and productive conversation,” Newton stated in a press release. “I forgave him. Bob has a long, irrefutable track record as a champion for inclusion and we continue to enjoy a positive relationship today. I consider him a friend.”

Word of Iger’s blunder unfold shortly via the group. But it was an indication of the affect Iger commanded throughout the firm, and his established observe file championing variety — together with pushing to get the Marvel hit “Black Panther” made and personally mentoring Black executives — that the failed joke had little influence on his standing. The incident ended up being an instance of how leaders who shortly and genuinely apologize can clean over errors. Newton would keep at Disney for 4 extra years, leaving the corporate in June.

The episode can also be emblematic of the significance of a unified communications staff. The remark by no means leaked to the media.

Had Chapek made an analogous error, it is uncertain executives, board members and staff would have been so forgiving.

Chapek’s gentle triumph

The “Don’t Say Gay” debacle was hardly a perfect prelude to Chapek’s contract renewal talks within the spring, which had been led by Arnold. But, as soon as once more, he did have excellent news to spotlight. Disney had weathered the Covid pandemic. In the primary quarter of 2022, Disney’s parks, experiences and merchandise section noticed revenues greater than double, to $6.7 billion, in contrast with the prior-year interval. It was time to look to the longer term.

Chapek outlined a daring imaginative and prescient to the board. He wished to remodel Disney into a contemporary media firm, with Disney+ a globally dominant streaming service. Disney analysis confirmed the primary grievance amongst Disney+ customers was its lack of basic leisure. Chapek meant to push Hulu and Disney+ collectively to present adults extra choices — a “onerous bundle,” he later known as it.

Despite difficulties throughout his tenure, the Disney board awarded Chapek, seen right here on Nov. 15, 2021, a contract extension in summer season 2022, to present him extra time to implement his imaginative and prescient.

Charles Krupa | AP

He additionally hoped to determine a job for Disney within the metaverse and employed 50 staff to give attention to “next generation storytelling,” consciously avoiding the time period “metaverse” to discourage derision. Several Disney executives privately mocked the trouble anyway, given the vagueness surrounding the complete idea. They questioned if Chapek was making an attempt too onerous to tell apart himself from Iger, in line with individuals accustomed to their considering.

Without Iger on the board, Chapek additionally felt emboldened to rethink ESPN and Disney’s different TV properties. In explicit, he wished to think about spinning off or promoting ABC and ESPN — an idea Iger had constantly dismissed (however later floated in a July 2023 interview with CNBC). When Iger was chairman, Chapek was so reluctant to broach the topic of promoting legacy media belongings that he’d rigorously therapeutic massage the language in slide displays to keep away from annoying Iger, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter.

Chapek argued that ESPN, underneath Disney, may have a future as a standalone digital enterprise, unbundled from conventional pay TV — “the hub of all streaming sports,” as he and Pitaro put it. Chapek wished followers to have the ability to watch any recreation on an ESPN app, irrespective of who owned the rights. To make that occur, Disney would want to strike partnership offers with each the leagues and competing providers corresponding to NBCUniversal’s Peacock, Apple TV+, Amazon Prime Video and Paramount+, which can or could not have been possible.

Chapek was additionally beginning to acquire traction with the Hollywood group. He’d brokered peace on Johansson with Lourd and repaired that relationship. Dana Walden, who changed Rice to steer Disney’s TV division, invited Chapek to her home to satisfy A-list showrunners and administrators.

A majority determined Chapek deserved extra time to implement his personal imaginative and prescient, and he obtained a comparatively brief contract extension, till July 2025. The message was clear: We consider in you — so long as you retain delivering outcomes.

Chapek interpreted the contract renewal as a certified victory, in line with individuals accustomed to his ideas on the time. He could not assist however view it within the lens of what it meant for Iger. On the one hand, an extension till 2025 will surely make Iger’s return much less probably. On the opposite, Chapek instructed colleagues, he feared Iger may flip up the warmth towards him — particularly now that Iger was now not sure by any fiduciary duties as chairman.

Chapek’s sudden demise

Iger spent the summer season of 2022 vacationing within the South Pacific on his yacht; engaged on his second ebook; attending the funeral of former Capital Cities/ABC CEO Thomas Murphy, a longtime mentor; making some private investments; and taking conferences with enterprise capital companies and tech startups that wished to enlist him as an advisor. In September, he joined the board of enterprise capital agency Thrive Capital, based by Josh Kushner.

Yet, as Chapek suspected and feared, Iger’s coronary heart remained at Disney. One buddy described Iger at the moment as “bored out of his mind,” although others famous he gave the impression to be having fun with retirement. Privately, Iger continued to speak with previous and current Disney executives about Chapek and the way forward for the corporate, with a number of urging him to return to Disney, in line with individuals accustomed to these conversations.

In the primary half of 2022, Disney was the worst performing inventory within the Dow Jones Industrial Average, down practically 40% as a part of the “great Netflix correction.” Netflix’s lack of subscriber development in January, mixed with rising rates of interest and the tip of the pandemic, had triggered the market to revalue streaming firms. Suddenly, merely rising Disney+ wasn’t sufficient cause for buyers to pump up Disney shares.

During the summer season, Iger reached out to Schake, the brand new communications head, to want her luck in her function. In flip, Schake invited him to dinner. They shared frequent acquaintances — particularly, former President Barack Obama and former first woman Michelle Obama. Iger and the Obamas are associates, and Schake was Michelle Obama’s former communications director.

Fearing Chapek could interpret the assembly the fallacious means, Schake instructed each the board and Chapek in regards to the meal. Chapek was perturbed, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter. Schake was presupposed to be his communications director, and already she was eating with the enemy.

The retired Iger, seen right here on Dec. 6, 2022, privately continued to speak with previous and current Disney executives about Chapek and the corporate, with a number of urging him to return to Disney, in line with individuals accustomed to these conversations.

David Dee Delgado | Reuters

Still, though Chapek could not shake his concern that Iger was plotting a return as CEO, Iger each privately and publicly denied this. Earlier that yr, he instructed journalist Kara Swisher the notion was “ridiculous.”

Things lastly got here to a head within the runup to Disney’s fourth-quarter fiscal earnings report.

By 2022, Chapek and CFO McCarthy had a dependable sample for earnings preparation. Disney board conferences are extremely choreographed, and govt displays are rehearsed advert nauseum. So, together with different executives, Chapek and McCarthy would rehearse displays for weeks. Then, when quarterly numbers had been launched publicly, Chapek and McCarthy would quarterback a convention name and question-and-answer session for fairness analysts. The pair would agree on all of the numbers and divvy up matters for the Q&A. There had been no surprises.

In late September, Chapek and McCarthy prepped the board on what to anticipate for the upcoming November 2022 quarter.

But this time, McCarthy started going off script. Not solely did she reference numbers and forecasts the 2 executives hadn’t mentioned, she bluntly instructed the board the quarter’s financials had been on tempo to be very dangerous, in line with individuals accustomed to what was stated on the assembly.

McCarthy instructed the board that Disney earnings that quarter would fall dramatically wanting Wall Street’s consensus estimate of 55 cents per share. Quarterly income could be greater than $1 billion decrease than projected. The quarter could be the corporate’s greatest miss relative to Wall Street consensus estimates in a decade, she stated.

McCarthy attributed this grim outlook partially to the corporate’s failure to change its streaming technique after the trade’s revaluation triggered by Netflix’s first-quarter lack of development. Disney now wanted to prioritize profitability, McCarthy argued. She thought Daniel was overhiring in DMED and that Chapek’s restructure had created duplications that wanted to be addressed by layoffs — one thing Chapek would announce in November.

Chapek was blindsided by McCarthy’s responses. He had no concept the numbers would examine so poorly with Street estimates. McCarthy hadn’t instructed him she could be sharing such a blunt evaluation of the enterprise, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter.

“How could this happen?” requested board member Mark Parker, in line with individuals accustomed to what was stated in the course of the assembly. Directors Safra Catz, Oracle’s CEO, and Derica W. Rice, previously president of CVS Caremark, peppered Chapek with questions on Disney’s forecasting methods and the way division heads shared finance info. Chapek struggled to reply and declined accountable anybody within the formal board assembly setting.

In an govt session alone with the board, Chapek argued that if something was amiss, it was McCarthy’s poor monetary administration. After all, the division CFOs reported to her. McCarthy both wasn’t sharing the numbers with him or hadn’t grasped how dangerous earnings could be, he stated, in line with individuals accustomed to the discussions. Chapek shared his frustration over McCarthy’s shocking diversion from the script with a number of of his colleagues. But he did not specific it to her straight, apart from telling her she’d unnecessarily upset the board, stated individuals accustomed to the interactions.

Besides, Chapek did not consider the outcomes had been as dire as McCarthy was portray them to be. He identified Disney+ was nonetheless including prospects at a torrid tempo — 12.1 million that quarter. As lengthy because the streaming service was on tempo to satisfy its aim of 215 million to 245 million subscribers by the tip of 2024, Chapek believed, the corporate was in fine condition. Disney ended that quarter with 164.2 million Disney+ subscribers.

“Kareem [Daniel] says we’re killing it!” he instructed a number of colleagues, in line with individuals accustomed to the conversations. In the earlier quarter, Disney shares had risen 5% after the corporate’s income and earnings exceeded analyst estimates. By Chapek’s reasoning, even when the fourth quarter was a disappointment, it was nonetheless only one quarter.

McCarthy instructed colleagues she hoped her honesty with the board would jar Chapek into realizing his rosy outlook of the enterprise wasn’t primarily based in actuality. McCarthy’s relationship with Daniel and his staff’s finance leaders had damaged down. McCarthy instructed colleagues DMED was supplying her with unreliable info, always altering its forecast, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter.

Disney’s 2022 administration retreat in Orlando fell a couple of weeks earlier than the November earnings name, and members of the DMED and finance groups gathered to determine a method. General counsel Horacio Gutierrez instructed colleagues that folks had been entitled to their very own opinions however not their very own details. He half-invited, half-forced McCarthy, Daniel, Schake, direct-to-consumer CFO Justin Warbrooke, head of investor relations Alexia Quadrani, Bryan Castellani, DMED’s govt vice chairman of finance, and a number of other others to gap up in a convention room for the majority of the retreat. They missed many of the scheduled enjoyable, corresponding to interacting with the animals at Animal Kingdom and attending to experience new theme park points of interest with out the traces, in line with individuals conscious of the conferences. Chapek had phased out the obligatory athletic exercise from the Iger period.

Bob Chapek arrives on the premiere of “Pinocchio” at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank on Sept. 7, 2022. When Chapek grew a beard, colleagues instructed him he ought to maintain it as a result of it “humanized” him.

Michael Buckner | Variety | Getty Images

Chapek attended just a few minutes of the primary technique session. He spent most of his time on the retreat collaborating in actions that might showcase his personable facet to staff. By this time, Chapek had grown a beard, which colleagues instructed him he ought to maintain as a result of it “humanized” him. When a number of of the executives locked within the convention room discovered Chapek was having enjoyable, together with petting a hippopotamus, their collective frustration with him grew, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter.

Coming out of the conferences, Schake and Quadrani instructed Chapek the response to the quarter could possibly be devastating. Chapek started referring to Schake, Quadrani and McCarthy as “the mean girls,” a reference to the 2004 Lindsay Lohan film, as a result of he felt they had been ganging up on him. Those who took a dark view of Disney’s prospects he known as “Eeyores,” a reference to Winnie the Pooh’s perpetually glum donkey buddy, in line with individuals accustomed to the conversations between Chapek and his workers.

On the day of the earnings name, executives met at Disney’s West 66th Street workplace in New York. The finance staff suggested Chapek to ship a sober message acknowledging that the streaming division’s internet working losses had been greater than double that of the identical interval the earlier yr — whereas emphasizing that Disney was enjoying an extended recreation and would in the end emerge stronger.

Chapek refused to strike an apologetic notice. McCarthy, specifically, was appalled at how cavalier Chapek appeared in regards to the state of the enterprise, in line with individuals accustomed to her ideas on the time. She was significantly aggravated that as an alternative of frankly addressing the outcomes, Chapek waxed on in regards to the promising ticket gross sales for Disneyland’s “Oogie Boogie Bash” Halloween occasion.

The day after the numbers had been launched, Disney’s share value dropped 13%, far underperforming the broader market.

The following days weren’t type to Chapek. Activist hedge fund Trian Partners, led by founding associate Nelson Peltz, took an $800 million stake in Disney, worrying board members that he could attempt to take a board seat and oust present administrators.

Separately, board member Catz privately instructed Chapek he was making an enormous mistake releasing the animated film “Strange World,” which featured an overtly homosexual character. Catz, who was on former President Donald Trump’s transition staff, instructed him the film was too polarizing and lower than Disney’s high quality requirements. She warned a poor efficiency would not play effectively with the board.

Catz declined to remark.

Disney’s “Strange World” options an overtly homosexual character. Chapek and different executives determined to launch it regardless of a board member’s warning that it could be polarizing and was lower than Disney’s high quality requirements. It was a box-office flop, shedding $200 million.

Disney

But Chapek and different Disney studio executives knew they’d must launch the film. The very last thing Disney wanted was to anger the LGBTQ group once more.

Disney launched the film on Nov. 23, 2022. It was a large flop, shedding Disney about $200 million.

Chapek’s failure to heed the warnings of the individuals round him irked many executives, together with some beforehand sympathetic to him. Walden, Bergman and others spoke privately to Iger, who suggested them that in the event that they wished to make a CEO change, they need to converse to the board en masse.

In a extremely uncommon transfer, board members additionally arrange discussions with Disney division heads, who hardly ever converse to administrators exterior formal conferences. Schake, McCarthy, Gutierrez, Walden, Bergman and D’Amaro all instructed both Arnold, Mark Parker or the complete board that they now not supported Chapek as CEO, in line with individuals accustomed to discussions. All declined to remark.

The board determined Disney wanted to make a CEO change. There was just one clear substitute.

Dana Walden, seen right here on April 29, 2022, changed Rice to steer Disney’s TV division. Walden requested Iger in November 2022 if he would think about returning to Disney as CEO.

Rich Polk | Getty Images

Walden and Bergman each reside close to Iger. On Nov. 12, every took a stroll with him within the neighborhood and instructed him they’d voiced their considerations to Arnold, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter. Walden requested Iger if he’d be open to returning. By this time, a number of different previous and current Disney executives had additionally urged Iger to come back again. Iger instructed Walden he’d think about it, though he did not inform his spouse, in line with an individual accustomed to the matter.

Early the subsequent week, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter, Walden deliberate one other stroll with Iger for three p.m. on Nov. 19. Shortly earlier than their scheduled stroll, Walden known as to inform Iger she’d by no means had any intention of taking that stroll: She had made the appointment to make sure he’d be accessible for a name from Arnold, who formally requested him to return. Walden declined to remark.

Iger and Bay talked it over. She instructed him that if the board was asking him to come back again, he ought to say sure.

The following day, Disney shocked its staff and Wall Street but once more. The board had fired Chapek, who wasn’t even allowed to ship a goodbye e mail. Less than three years after he gave up his job, Iger was as soon as once more the CEO of Disney.

Around Christmas, Schake, Quadrani and McCarthy obtained presents from a colleague: pink sweaters, an homage to their “mean girl” historical past.

In a reference to the 2004 Lindsay Lohan film, Chapek started referring to CFO Christine McCarthy, prime communications govt Kristina Schake and head of investor relations Alexia Quadrani as “the mean girls,” as a result of he felt they had been ganging up on him. A colleague later despatched the three ladies pink sweaters in tribute.

Getty Images

Iger’s rocky return

Michael Eisner and Bob Iger have been two of Disney’s most storied CEOs, and there are some hanging similarities between them. Neither wished to depart the corporate. Both had bother naming a successor.

Eisner declined to remark for this story.

After 21 years within the job, Eisner misplaced his grip on the board and Disney’s shareholder base. Disney’s inventory plummeted, and Eisner resigned. That would as soon as have appeared an unthinkable destiny for Iger, who’s now in yr 16.

And but Disney is arguably going through extra issues than at any time in its historical past. The linear TV promoting market is collapsing as subscribers cancel cable TV by the hundreds of thousands every year. ABC has completed final among the many main broadcast networks in prime-time rankings for the previous two years. The collapse of cable is even worse for ESPN, which derives most of its income from affiliate charges from pay TV distributors. Customers of Charter Communications, the second-largest U.S. pay-TV supplier after Comcast, final week realized that every one Disney-owned broadcast and cable networks had been dropped from Charter’s Spectrum service amid a combat over programming payment will increase. Attendance at Walt Disney World slipped this summer season.

On May 5, 2005, Disney CEO Michael Eisner and CEO-elect Bob Iger pose with Mickey Mouse in the course of the kickoff of Disneyland’s 50th anniversary celebration.

Mark Rightmire | MediaNews Group | Orange County Register through Getty Images

In the previous few months, Disney has laid off 7,000 individuals. The firm is paying down practically $45 billion in debt — a lot of which stems from the 2019 acquisition of Fox, which seems to have been a large overpay by Iger and his technique staff. In August, Disney shares closed at their lowest level since 2014. Since Iger returned as CEO in November, shares have slumped greater than 11%. The S&P 500 is up greater than 13% over the identical interval.

Since returning, Iger has undone Chapek’s streaming reorganization, fired McCarthy as CFO, and put Bergman and Walden again answerable for finances and distribution selections for his or her content material. But these strikes have not been, and are unlikely to be, a fast repair for the corporate’s woes. Under Bergman’s watch, Disney has had a string of film failures. This yr, the live-action “The Little Mermaid,” “Indiana Jones and the Dial Of Destiny” and “Haunted Mansion” have dissatisfied on the field workplace. The Hollywood Reporter known as the latter “one of the worst starts ever among Disney’s live-action reimaginings of theme park attractions or classic animated films.”

Halle Bailey stars as Ariel in Disney’s live-action “The Little Mermaid.” In 2023, Disney films together with “The Little Mermaid,” “Indiana Jones and the Dial Of Destiny,” and “Haunted Mansion” have dissatisfied on the field workplace.

Disney

Meanwhile, Disney’s streaming division misplaced $512 million within the quarter ended July 1. The firm nonetheless goals to interrupt even on streaming by the tip of 2024. It hasn’t readjusted its goal, which was reset in August 2022, of getting 215 million to 245 million Disney+ subscribers by the tip of subsequent yr — 135 million to 165 million excluding India.

Still, one one who helped set these targets stated “lightning would have to strike five times” for Disney to achieve them. At the tip of the newest quarter, Disney+ had 146.1 million subscribers — 105.7 million excluding India. That’s about 16 million fewer Disney+ prospects than the corporate had on Oct. 1, 2022, an indication that Disney has deprioritized including streaming subscribers, particularly in India, and that total development has slowed.

Disney in August introduced a 27% hike within the value of Disney+, to $13.99 per 30 days, in an effort to speed up streaming profitability. In late July, Atlantic Equities analyst Hamilton Faber pushed again his projected date for Disney to interrupt even in streaming to 2026. Consensus analyst estimates name for Disney to finish 2024 with about 50 million fewer Disney+ subscribers than the low finish of its 2024 aim.

“With Iger-led Disney raising Disney+ pricing to push toward profitability, the Chapek era sub goals appear unattainable,” stated MildShed media analyst Rich Greenfield. “However, with content engines all sputtering at the same time, sub growth is the least of Disney’s problems.”

WATCH: Disney CEO Bob Iger’s unique July 2023 CNBC interview

Take the ‘A’

During Chapek’s tenure as CEO, Disney misplaced greater than 1 / 4 of its market worth. The pandemic clearly performed a job in that. But Chapek ought to, in his personal phrases, “take the A” — accountability — for a few of his failures.

Breaking with Iger was clearly not a sound technique. Iger had nominated each member of the board, constructed the corporate in its fashionable kind, and repeatedly struggled to stroll away from the job. Had Chapek been capable of higher compartmentalize his insecurity over his job standing, it is doable he may have brokered a peace along with his boss.

But Iger should additionally take some blame for Disney’s botched succession. Maybe Chapek was by no means the best particular person to run Disney — however Iger was the one who picked him. For the vast majority of Chapek’s tenure as CEO, Iger’s private and non-private angle towards him wavered between neutrality and energetic disapproval. Right from the beginning, he did not champion the CEO he’d chosen. If Iger, consciously or not, undermined Chapek at each flip, that is on Iger, too.

Iger agrees he bears accountability, in line with individuals who know him. That’s a part of why he returned to the job, the individuals stated. In July, at a personal panel on the Allen & Co. convention in Sun Valley, Idaho, Iger instructed the group that he had did not vet his successor correctly and that he will not confuse operational observe file for management once more, in line with individuals in attendance.

The whole episode has additionally revealed the constraints of “Disney nice.” Avoiding face-to-face battle, at the very least on the CEO and board degree, fostered an atmosphere the place Iger and Chapek could not hash out their variations. Executives who overtly challenged others — Mayer, Rice, McCarthy — had been in the end dinged for his or her frankness. Iger by no means went on to Chapek along with his considerations, though Iger was Chapek’s boss. Chapek largely averted mentioning his fears with Iger slightly than confronting the 2 males’s points.

The systematic nature of the Disney board conferences did not assist. Directors have lately realized that conferences are dominated by pointless formality, which has been a detriment to candid dialogue, in line with individuals accustomed to the matter. Board members have pushed for extra free-form dialogue, the individuals stated.

Succession planning is likely one of the few obligations that fall squarely on company boards. Turning Disney over to a CEO with out giving him management of inventive — the center of the corporate — led to confused management and a near-inevitable energy battle. By skipping the one-on-one conferences with Chapek earlier than appointing him, the board did not understand how his persona would mesh with Iger’s if management clashes arose.

So what occurs now? Iger does wish to retire on the finish of 2026, in line with individuals accustomed to his considering, and has stated he is labored more durable previously 9 months than at any time in his profession. He does not need his legacy to be marred by a failure to decide on a worthy successor.