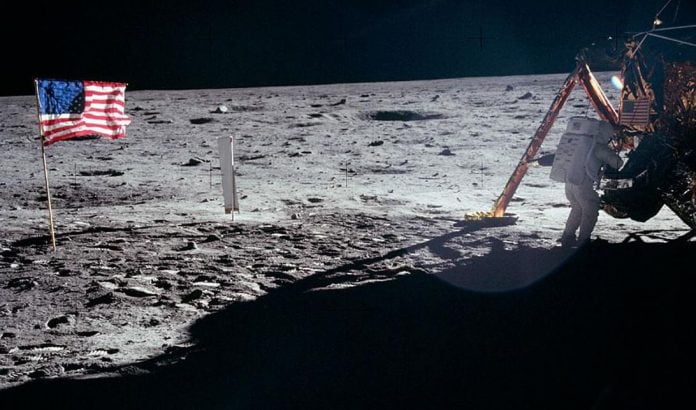

Work provided for the Apollo objectives assisted us transform worldwide interactions, weather condition forecasting, transport and, yes, computer systems.

NASA

This story belongs to To the Moon, a series checking out mankind’s very first journey to the lunar surface area and our future living and dealing with the moon.

“If we can get a man to the moon, why can’t we…” is a typical expression to compare a huge accomplishment with a much hoped-for one that appears easy however stays out of our grasp.

It’s a testimony to NASA’s success with the Apollo moon landing program that it’s still the bar by which other human accomplishments are evaluated. NASA had more than a quarter million Americans dealing with the task, establishing not simply spacecraft and spacesuits however likewise exercising the mathematics essential to land a spacecraft 240,000 miles away on the moon and securely return it and its team to Earth.

Click here for To The Moon, a CNET multipart series analyzing our relationship with the moon from the very first landing of Apollo 11 to future human settlement on its surface area.

Robert Rodriguez/CNET

But as we approach the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s historical landing, some still question if it deserved the expense, whether we showed anything more than hubris, composes Charles Fishman in One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission that Flew Us to the Moon. Fishman’s book, out Tuesday, isn’t as much a common historic stating of the program as it is an extensive evaluation of crucial minutes and individuals in the lead-up to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepping onto the lunar surface area in July 1969.

Drawing on his years as an area program reporter, Fishman provides a detail-rich take a look at the United States area race with the Soviets. (Did you understand the moon has an odor?) Along with mindful, easy-to-understand descriptions of the innovation included, Fishman likewise uses viewpoint on where that trip has actually taken us in the 50 years given that the very first landing.

(Disclosure: Simon & Schuster, publisher of One Giant Leap, is owned by CNET moms and dad CBS.)

Born out of the fear of falling behind the Russians technologically, the US space program unfolded against the backdrop of a tumultuous decade of political and cultural unrest. While NASA scientists worked to get humans to the moon, protests, riots and deadly encounters reached every corner of the nation.

Things were changing fast, but perhaps most telling is that little of the technology necessary to get us to the moon existed when President John F. Kennedy vowed in 1961 to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

How do we get to the moon?

A central challenge was figuring out how exactly we were going to get to the moon. In one of the front-runner proposals, a monolithic rocketship would land on the surface of the moon, just like in children’s cartoons from the time. Another proposal called for assembling the rocket to the moon in Earth’s orbit, and likely would require some kind of space station.

The Eagle — the first lunar module to land on the moon — in action

NASA

After years of presentations falling on largely deaf ears, a fairly low-level NASA engineer penned an unorthodox and impolitic memo to NASA’s second in command. His proposal called for a main spaceship to assume a “parking orbit” around the moon and for a detachable lunar module to make the final journey to the moon’s surface. The advantage to this plan was that all the fuel and equipment necessary for the trip back to the Earth wouldn’t have to be lifted off the surface of the moon.

That lunar-orbit rendezvous approach would ultimately be approved and used for each Apollo mission to the moon.

By Fishman’s count, NASA built 15 Saturn V rockets, 18 command modules and 13 lunar modules. The 11 manned Apollo missions spent 2,502 hours in space — about 100 days in total — but required 2.8 billion work-hours on Earth to get them there. Essentially, every hour in space required 1 million hours of work back home.

In all, it was mankind’s greatest single undertaking.

“It’s possible that no other project in history has demanded the sheer density of preparation required by Apollo,” Fishman writes.

‘I’m not interested in space’

But there was skepticism about the project’s value soon after Kennedy announced the effort. The New York Times noted in a January 1962 editorial that the US could build 75 to 120 universities with the money being spent on moon missions.

Indeed, Kennedy was reluctant to earmark the then-astronomical sum of $7 billion. Until the Soviets beat the US into space with the Yuri Gagarin orbit and the US’ disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, Kennedy had little interest in space. Soon he was a vigorous proponent, trying to impress upon NASA chief Jim Webb that being first to the moon should be “the top priority program.”

President John F. Kennedy vowed to land astronauts on the moon “in this decade” during his famous We Choose to go to the Moon speech at Rice University in 1962.

NASA

“Everything we do ought to be really tied into getting onto the moon ahead of the Russians,” Kennedy said, according to a once-secret recording of the meeting cited by Fishman. “Otherwise, we shouldn’t be spending this kind of money, because I’m not that interested in space.”

It’s good to learn about space, Kennedy acknowledged. “We’re ready to spend reasonable amounts of money. But we’re talking about these fantastic expenditures which wreck our budget.”

It didn’t help that he didn’t have the full support of the US scientific community. In testimony before the Senate, Science magazine editor Philip Abelson, a physicist and contributor to the creation of the atomic bomb, cast doubt on the value of the program.

The “diversion of talent to the space program is having and will have direct and indirect damaging effects on almost every area of science, technology and medicine,” he said.

Of course, Apollo did go forward, but some may still wonder what was accomplished, since we have no permanent colonies on the moon and haven’t even sent a human back in more than 45 years. To answer that question, one need only look around at the world today. Work done for the Apollo missions helped us revolutionize global communications, weather forecasting, transportation and, yes, computers.

“The culture of manned space travel helped lay the groundwork for the digital age,” Fishman writes. “Space didn’t get us ready for space; it got us ready for the world that was coming on Earth.”

Space gets us ready for the digital age

In an age when technology was largely associated with the military, Apollo helped bring it to the masses, ushering in the digital revolution of the 1970s. Microchips and laptop computers would have existed without the Apollo missions, but they also would have existed without Intel, Microsoft and Apple, Fishman argues.

Key to the mission was the Apollo Guidance Computer, the command module’s onboard computer, sometimes referred to as “the fourth crew member.” Designed by the MIT Instrumentation Lab, it was responsible for the guidance, navigation and control of the spacecraft. It included one of the first examples of what we now call a user interface – the DSKY, which stood for display and keyboard.

The Apollo Guidance Computer had an early version of what we would eventually come to call a user interface.

Bruce M. Yarbro/Smithsonian Institution

The keyboard was eight inches square and seven inches deep, but contained no letters, only numbers. It also had early versions of the function keys found on consumer computers decades later: ENTR, RSET and CLR, among others.

For its time, the AGC was groundbreaking, but as is often pointed out in a condescending way, was woefully underpowered compared with many devices we take largely for granted today. The AGC had only 73 kilobytes of memory, and less than 4K of that was RAM, referred to as erasable memory 50 years ago.

The AGC could execute 85,000 instructions a second, an impressive feat for its time, Fishman notes. But it’s about two-millionths of 1% percent of the computing power of the iPhone X, which can handle 5 trillion instructions per second. But that’s not what you should be in awe of, he says.

“Few of us would depend exclusively on our occasionally erratic iPhones to fly us to the moon, let alone depend on one of our kitchen appliances,” Fishman writes. “The miracle is just the opposite; it’s what the engineers, scientists and programmers at MIT were able to do with such austere computing resources; it’s the amount of work they were able to wring out of the AGC and the amount of reliability they were able to build into it.”

In the process, he says, “the Apollo computer became an example and a foundation for the digital work and the digital world that followed.”

But the emerging technology wasn’t without conflicts, especially between the computer’s hardware and software – at the time such a new phrase that some treated it as a joke. A main problem was fitting all the necessary instructions to land on the moon and get back to Earth into a bloated string of code that took up nearly 20% more memory than the computer held.

Fishman includes a lot of details from the principals, offering an inside look at some of the challenges facing the program. A largely unsung hero of the program was Bill Tindall, chief of Apollo Data Priority Coordination, who wrote memos that came to be known as Tindallgrams. The well-written dispatches were serious and sometimes humorous dissections of technical problems facing the program and quickly became required reading for those in the program.

Apollo 11 moon landing: Neil Armstrong’s defining moment

See all photos

In one such memo Fishman relates, Tindall lamented about a light on the lunar module’s dashboard that came on when there was 2 minutes of fuel remaining.

“This signal, it turns out, is connected to the master alarm – how about that!” Tindall wrote. “In other words, just at the most critical time in the most critical operation of a perfectly nominal lunar landing mission, the master alarm with all its lights, bells and whistles will go off.

“This sounds lousy to me. If this is not fixed, I predict the first words uttered by the first astronaut to land on the moon will be, ‘Gee whiz, that master alarm certainly startled me.'”

Those challenges eventually led to achievements we benefit from today. NASA’s demand for integrated circuits — the first computer chips — helped create the market for chips and cut their price by 90% in five years. It also improved their manufacturing quality.

Because the chips were going to the moon, MIT had to be sure they could withstand extreme conditions, so they were X-rayed, centrifuged, baked in an oven and tested for leaks. MIT’s quality standards meant that entire orders of chips were rejected, leading to a dramatic reduction in failure rates.

“What NASA did for semiconductor companies was to teach them to make chips of near-perfect quality, to make them fast, in huge volumes and to make them cheaper, faster, and better with each year,” he writes.

“That’s the world we’ve all been benefitting from for the 50 years since.”