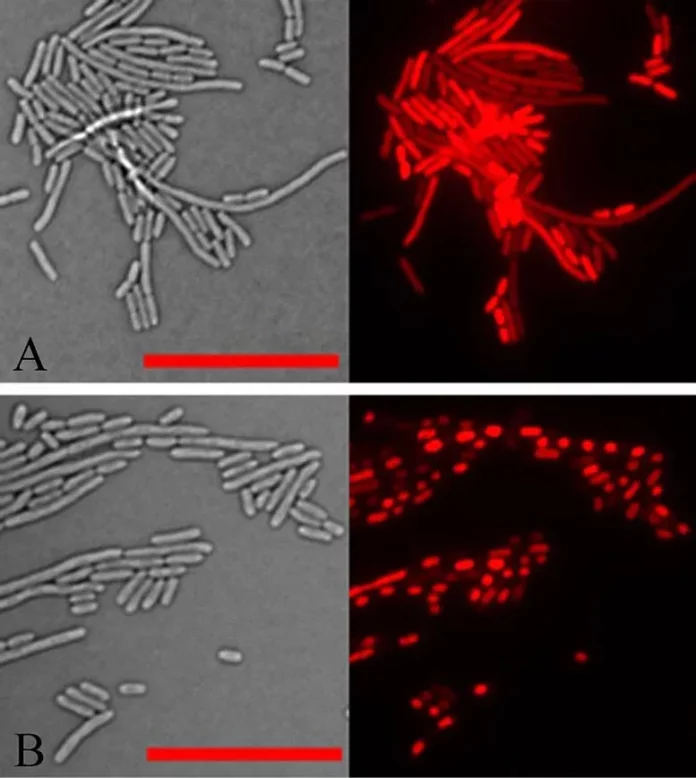

Light microscope pictures of E. coli cells in transmitted mild (left) and mirrored mild that picks up the purple fluorescence of a dye staining the cells’ DNA (proper). In regular cells (higher panel), the DNA is unfold all through the cells. But in cells expressing the aberrant plant protein recognized on this examine (backside panel) all of the DNA inside every cell has collapsed right into a dense mass. DNA condensation additionally happens after micro organism have been handled with aminoglycoside antibiotics. Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory

Discovery of an aberrant protein that kills bacterial cells might assist unravel the mechanism of sure antibiotics and level the best way to new medicine.

An aberrant protein that’s lethal to micro organism has been found by biologists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and their collaborators. In a paper that might be revealed right this moment (April 29, 2022) within the journal PLOS ONE, the scientists describe how this erroneously constructed protein mimics the motion of aminoglycosides, a category of antibiotics. The newly discovered protein might function a mannequin for scientists to decipher the specifics of these drugs’ deadly impression on micro organism—and probably level the best way to future antibiotics.

“Identifying new targets in bacteria and alternative strategies to control bacterial growth is going to become increasingly important,” mentioned Brookhaven biologist Paul Freimuth, who led the analysis. Bacteria have gotten proof against a number of routinely used antibiotics, and lots of scientists and clinicians are involved about the opportunity of large-scale epidemics brought on by these antibiotic-resistant micro organism, he defined.

“What we’ve discovered is a long way from becoming a drug, but the first step is to understand the mechanism,” Freimuth mentioned. “We’ve identified a single protein that mimics the effect of a complex mixture of aberrant proteins made when bacteria are treated with aminoglycosides. That gives us a way to study the mechanism that kills the bacterial cells. Then maybe a new family of inhibitors could be developed to do the same thing.”

Following an attention-grabbing department

The Brookhaven scientists, who usually deal with energy-related analysis, weren’t occupied with human well being once they started this venture. They have been utilizing E. coli micro organism to review genes concerned in constructing plant cell partitions. That analysis might assist scientists learn to convert plant matter (biomass) into biofuels extra effectively.

Brookhaven Lab biologist Paul Freimuth and co-author Feiyue Teng, a scientist in Brookhaven Lab’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN), on the mild microscope used to picture micro organism on this examine. Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory

But once they turned on expression of 1 explicit plant gene, enabling the micro organism to make the protein, the cells stopped rising instantly.

“This protein had an acutely toxic effect on the cells. All the cells died within minutes of turning on expression of this gene,” Freimuth mentioned.

Understanding the idea for this fast inhibition of cell development made an excellent analysis venture for summer season interns working in Freimuth’s lab.

“Interns could run experiments and see the effects within a single day,” he mentioned. And perhaps they might assist determine why a plant protein would trigger such dramatic injury.

Misread code, unfolded proteins

“That’s when it really started to get interesting,” Freimuth mentioned.

The group found that the poisonous issue wasn’t a plant protein in any respect. It was a strand of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, that made no sense.

This nonsense strand had been churned out by mistake when the bacteria’s ribosomes (the cells’ protein-making machinery) translated the letters that make up the genetic code “out of phase.” Instead of reading the code in chunks of three letters that code for a particular amino acid, the ribosome read only the second two letters of one chunk plus the first letter of the next triplet. That resulted in putting the wrong amino acids in place.

“It would be like reading a sentence starting at the middle of each word and joining it to the first half of the next word to produce a string of gibberish,” Freimuth said.

The gibberish protein reminded Freimuth of a class of antibiotics called aminoglycosides. These antibiotics force ribosomes to make similar “phasing” mistakes and other sorts of errors when building proteins. The result: all the bacteria’s ribosomes make gibberish proteins.

“If a bacterial cell has 50,000 ribosomes, each one churning out a different aberrant protein, does the toxic effect result from one specific aberrant protein or from a combination of many? This question emerged decades ago and had never been resolved,” Freimuth said.

According to the current findings, just a single aberrant protein can be sufficient for the toxic effect.

That wouldn’t be too farfetched. Nonsense strands of amino acids can’t fold up properly to become fully functional. Although misfolded proteins get produced in all cells by chance errors, they usually are detected and eliminated completely by “quality control” machinery in healthy cells. Breakdown of quality control systems could make aberrant proteins accumulate, causing disease.

Messed-up quality control

The next step was to find out if the aberrant plant protein could activate the bacterial cells’ quality control system—or somehow block that system from working.

Freimuth and his team found that the aberrant plant protein indeed activated the initial step in protein quality control, but that later stages of the process directly required for degradation of aberrant proteins were blocked. They also discovered that the difference between cell life and death was dependent on the rate at which the aberrant protein was produced.

“When cells contained many copies of the gene coding for the aberrant plant protein, the quality control machinery detected the protein but was unable to fully degrade it,” Freimuth said. “When we reduced the number of gene copies, however, the quality control machinery was able to eliminate the toxic protein and the cells survived.”

The same thing happens, he noted, in cells treated with sublethal doses of aminoglycoside antibiotics. “The quality control response was strongly activated, but the cells still were able to continue to grow,” he said.

Model for mechanism

These experiments indicated that the single aberrant plant protein killed cells by the same mechanism as the complex mixture of aberrant proteins induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics. But the precise mechanism of cell death is still a mystery.

“The good news is that now we have a single protein, with a known amino acid sequence, that we can use as a model to explore that mechanism,” Freimuth said.

Scientists know that cells treated with the antibiotics become leaky, allowing toxic levels of things like salts to seep in. One hypothesis is that the misfolded proteins might form new channels in cellular membranes, or alternatively jam open the gates of existing channels, allowing diffusion of salts and other toxic substances across the cell membrane.

“A next step would be to determine structures of our protein in complex with membrane channels, to investigate how the protein might inhibit normal channel function,” Freimuth said.

That would help advance understanding of how the aberrant proteins induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics kill bacterial cells—and could inform the design of new drugs to trigger the same or similar effects.

Reference: “A polypeptide model for toxic aberrant proteins induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics” 29 April 2022, PLOS ONE.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258794

This work was supported by a Laboratory Directed Research and Development award from Brookhaven Lab and in part by the DOE Office of Science, Office of Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) under the Visiting Faculty Program (VFP). Additional funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) supported students participating in internships under NSF’s Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Talent Expansion Program (STEP) and the Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation (LSAMP) program.