Summer Haag and Clyde Kertzer, taking part in a CU Boulder REU, negated the long-held local-global opinion in number theory by checking out Apollonian circle packagings. Their research study highlighted the imaginative and uncharted elements of mathematical expedition. Credit: SciTechDaily.com

Summer Haag and Clyde Kertzer made significant news in the mathematics world while dealing with a summer season research study job.

Prior to the end of the 2022-2023 scholastic year, college student Summer Haag and junior Clyde Kertzer were trying to find summertime research study chances in mathematics, their topic of research study.

It was an REU (Research Experience for Undergrads) with Katherine (Kate) Stange, CU Boulder associate teacher in the Department of Mathematics, and James Rickards, a postdoctoral scientist in the very same department, that captured their eye, as it handled a subject in which they both had an abiding interest: number theory.

“I knew in undergrad that number theory is what I wanted to do,” statesHaag “When I saw Kate and James were doing a number theory REU, I said, ‘That one! I want that one!’”

“I’ve taken a bunch of number theory courses here at CU that I’ve really enjoyed,” states Kertzer, who withdrew his applications to other REUs when he was accepted into the one with Stange andRickards “I was super excited.”

Graduate trainee Summer Haag and junior Clyde Kertzer took part in an REU concentrating on number theory at CU Boulder, led by Katherine Stange and JamesRickards Their expedition of Apollonian circle packagings challenged the commonly accepted local-global opinion in mathematics. Credit: CU Boulder

The REU would check out a branch of number theory called Apollonian circle packagings, which are fractals, or relentless patterns, comprised of boundless circles simply touching each other however never ever overlapping.

Neither Haag nor Kertzer had much experience with circle packagings.

“I’d seen quadratic forms before, and I’d seen Mobius inversions, but I’d never seen them pertaining to circle packings,” statesHaag “I was excited to learn that stuff.”

“I went to the library and got a book, the only book I could find on circle packings, and started reading,” states Kertzer.

CU Boulder trainees Clyde Kertzer and Summer Haag negated a longstanding opinion in mathematical number theory throughout their summertime research study experience. Credit: CU Boulder

Room to Explore

For the very first couple of weeks of the REU, Stange and Rickards offered Haag and Kertzer the background details they ‘d require for the job and taught them how to utilize code that Rickards had actually established to collect information on circle packagings. After that, they offered Haag and Kertzer space to check out.

“We set out with a fun project idea that would give students a chance to experience research by collecting data, looking for patterns and proving them,” statesStange “We didn’t have a very definitive goal.”

“We had a long list of possible problems to explore,” Rickards includes. “There was no real end goal in sight.”

That altered, nevertheless, when Haag and Kertzer’s expeditions produced information that called a widely known mathematics opinion into concern.

The local-global opinion, commonly accepted for the much better part of 20 years, anticipates the curvatures of the circles inside a circle packaging. According to this opinion, if a scientist understands the curvatures of a couple of circles in a packaging (the “local” circles), that scientist can then forecast the curvatures of the circles in the remainder of the packaging (the “global” circles).

Time and once again, proof appeared to support the local-global opinion, to the point that practically everybody acquainted with it presumed it held true.

“Even though it hadn’t been proven, it was almost guaranteed to be true,” states Haag.

CU Boulder scholars Katherine Stange (left) and James Rickards research study number theory, an element of that includes Apollonian circle packagings. Credit: CU Boulder

Two Numbers Instead of One

But then, while getting in numbers into Rickards’ code, Haag and Kertzer chose to do something that had not yet been done. Instead of getting in one number into the code, they went into 2 and took a look at the resultant packagings.

That’s when things got intriguing. Numbers that, according to the local-global opinion, must have appeared together in the very same packagings didn’t.

Stange compares the scenario to a prison. It was as though the numbers that were expected to be secured had actually dug a tunnel when nobody was looking and left.

Haag, Kertzer, Stange and Rickards all understood what this information suggested for the local-global opinion, which is why Rickards’ instant response was to verify his code for mistakes. But there were none. The code was proper. The local-global opinion, on the other hand, was not.

Over the next couple of days, Stange and Rickards assembled an evidence of their findings, working so quick, so feverishly therefore exactly that Haag and Kertzer could not assist however be motivated.

“It was really impressive,” statesKertzer “That’s the point where we want to be as mathematicians.”

The 4 released a paper in the preprint server arXiv with a title as unambiguous as its material is mind-blowing: “The Local-Global Conjecture for Apollonian Circle Packings Is False.”

Not bad for a summer season research study job.

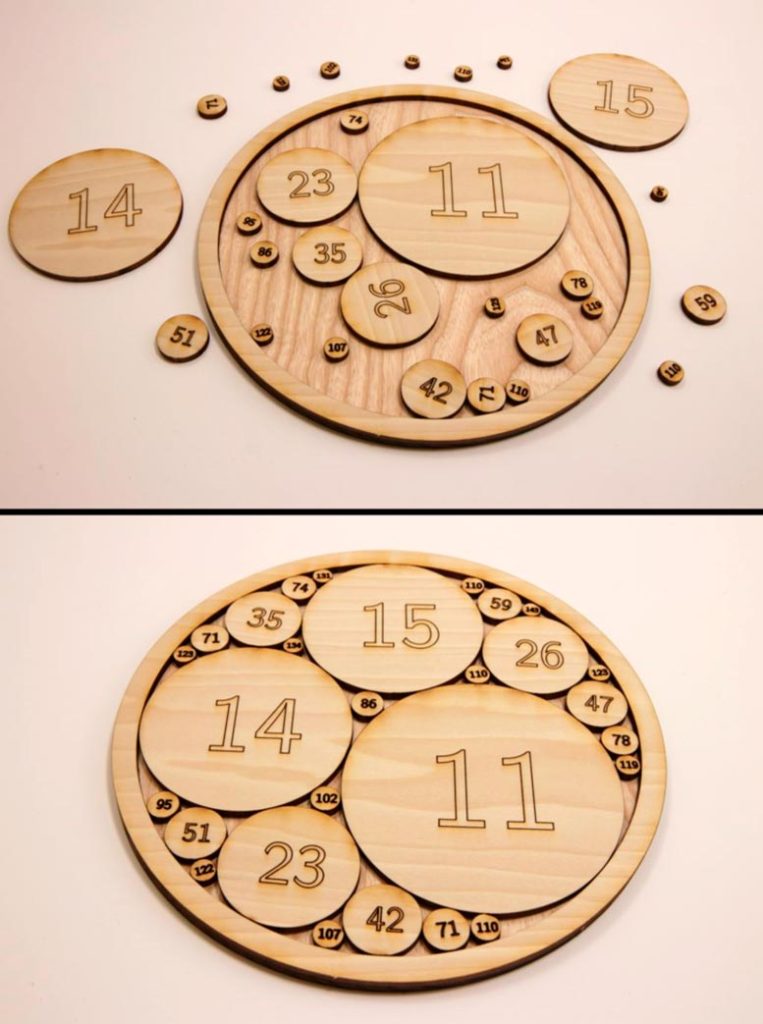

Katherine Stange partnered with engineering PhD graduate Daniel Martin to develop a pattern for an Apollonian circle packaging puzzle laser cut from wood. Credit: CU Boulder

The Playful Side of Math

But what Haag and Kertzer discovered much more rewarding than negating a significant exceptional opinion was experiencing first-hand the imaginative side of mathematics research study. It wasn’t all solutions and guidelines. It was instinct, expedition, play.

“Some advice Kate gave me will stick with me for a while,” Kertzer remembers. “‘If you’re not sure, just follow your nose.’”

Math research study, Stange describes, “often feels like exploring a jungle. You aren’t sure what you’ll find, but the creativity comes in deciding what leaf to turn over, which path to take, what questions you are trying to answer, and how you will go about answering them. Some of the deepest insights in mathematics come from creative leaps connecting apparently unconnected ideas.”

Luckily for Haag and Kertzer, there is plenty more jungle to check out.

“Some of my students are so thoroughly confused that I want to do research in math,” Haag states. “They’re like, ‘Isn’t math done? How many questions could possibly be unsolved in math?’”

Haag smiles when she responds to: “So many.”