In a research study released just recently in Ecology and Evolution, a global group of scientists concentrated on what can occur to ocean environments when fishing pressure increases or reduces, and how this varies in between tropical to temperate marine environments. The group, led by Elizabeth Madin, scientist at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in the University of Hawai’i (UH) at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), discovered environments do not react widely to fishing.

There has actually been much dispute about the degree to which ocean environments are affected by fishing, likewise described “top-down forcing” since such modifications happen when predators at the top of the food web are eliminated, versus the accessibility of nutrients and other resources in an environment, described “bottom-up forcing.”

“Examples from a variety of marine systems of exploitation-induced, top-down forcing have led to a general view that human-induced predator perturbations can disrupt entire marine food webs, yet other studies that have found no such evidence provide a counterpoint,” stated Madin.

A big shoal of herbivorous surgeonfish (Acanthurus triostegus) swims among tropical reef corals. Credit: Elizabeth Madin, University of Hawai’i

Madin dealt with a fantastic group of marine ecologists from all over the world, especially those from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (OBJECTIVES) and the University of Tasmania (UTas). Using time-series information for 104 reef neighborhoods covering tropical to temperate Australia from 1992 to 2013, they intended to measure relationships amongst populations of predators, victim, and algae at the base of the food web; latitude; and exploitation status over a continental scale.

As anticipated, no-take marine reserves–where fishing is forbidden–resulted in long-lasting boosts in predator population sizes.

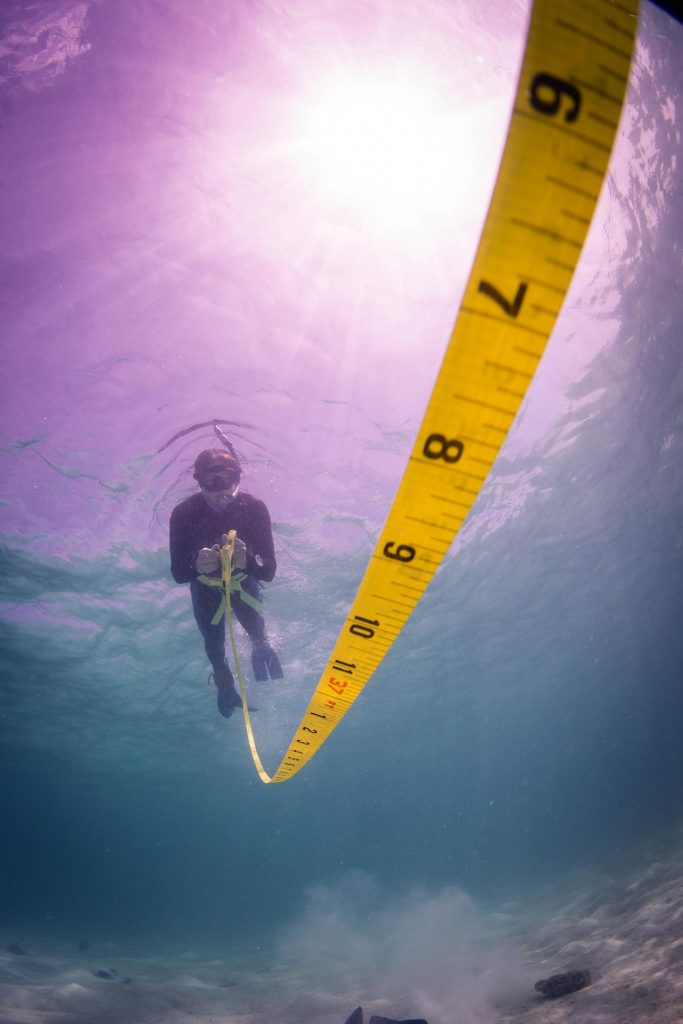

A scuba diver rolls up a transect tape upon conclusion of a study at Heron Island within northern Australia’s tropical Great Barrier Reef. Credit: Brian Sullivan

“This is good news for fishers, because as populations increase, the fish don’t recognize the reserve boundaries and are likely to ‘spill over’ into adjacent areas where fishing is allowed, creating a kind of insurance policy whereby marine reserves ensure the ability of fishers to catch fish into the future,” stated Madin.

Surprisingly however, the group discovered that in the tropics, the system tends to be driven mainly by bottom-up requiring, whereas chillier, temperate environments are more driven by top-down requiring.

“I assumed at the start of the project that in places where fishing pressure was high and predators were depleted, we would see consequent increases in the population sizes of the predators’ prey species, and the decreases in the prey’s prey species,” described Madin. “However, in the tropical part of our study system, that is, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, this simply wasn’t the case. This result had me scratching my head for quite some time, until I realized that this type of domino effect, called a trophic cascade, is simply a real, but rare, phenomenon in the topics.”

These type of continent-scale analyses are just possible with big, long-lasting datasets.

This research study depended on information from the OBJECTIVES long-lasting reef keeping an eye on program and the UTas Australian Temperate Reef Collaboration–producing one massive, continental-scale reef dataset.

“Only by looking at the very big picture, it turned out, were we able to find these trends,” stated Madin.

Predator loss is now an internationally prevalent phenomenon that touches almost every marine community on earth. Ecosystem destabilization is a widely-assumed repercussion of predator loss. However, the level to which top-down versus bottom-up requiring predominates in various kinds of marine systems is not definitively comprehended.

A meat-eating lobster (Jasus edwardsii) within a kelp and other macroalgal-dominated environment on among Australia’s numerous southerly, temperate reefs. Credit: Graham Edgar, University of Tasmania

“Understanding how our fisheries are likely to impact other parts of the food web is important in making the best possible decisions in terms of how we manage our fisheries,” stated Madin. “By understanding how coral reef food webs are likely to respond to fishing pressure, or conversely to marine reserves, we can make more informed decisions about how much fishing our reefs can safely handle. Likewise, this knowledge gives us a better idea of what will happen when we create marine reserves designed to serve as an insurance policy so communities can continue to catch fish long into the future.”

Madin was just recently given a prominent PROFESSION award, provided by the National Science Foundation in assistance of early-career professors who have the possible to work as scholastic good example in research study and education. With the financing, Madin will concentrate on comprehending what food web interactions can expose about how reef worldwide are faring as fishing pressure increases or reduces. Interwoven with this research study program will be an education and outreach program to assist trainees establish innovative technological abilities pertinent to marine research study and assistance trainees and the general public comprehend the value of reef to Hawai’i through visual arts, particularly, the production of reef-inspired public murals.

Reference: “Latitude and protection affect decadal trends in reef trophic structure over a continental scale” by Elizabeth M. P. Madin, Joshua S. Madin, Aaron M. T. Harmer, Neville S. Barrett, David J. Booth, M. Julian Caley, Alistair J. Cheal, Graham J. Edgar, Michael J. Emslie, Steven D. Gaines and Hugh P. A. Sweatman, 29 June 2020, Ecology and Evolution.

DOI: 10.1002/ece3.6347