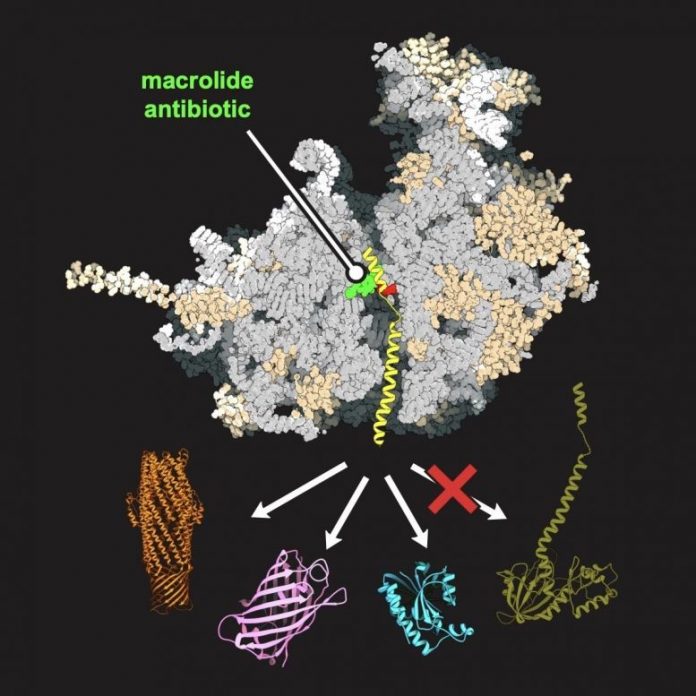

An antibiotic (green), bound in the human-like yeast ribosome (gray), enables synthesis of some proteins (represented in orange, purple, and blue) however not others (dark green). Credit: Maxim Svetlov/UIC

UIC scientists show that drugs developed for germs have possible to act upon human cells.

According to scientists at the University of Illinois Chicago, the prescription antibiotics utilized to deal with typical bacterial infections, like pneumonia and sinus problems, might likewise be utilized to deal with human illness, like cancer. Theoretically, a minimum of.

As laid out in a brand-new Nature Communications research study, the UIC College of Pharmacy group has actually displayed in lab experiments that eukaryotic ribosomes can be customized to react to prescription antibiotics in the exact same method that prokaryotic ribosomes do.

Alexander Mankin, the Alexander Neyfakh Professor of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy at the UIC College of Pharmacy. Credit: UIC Photo Services/UIC

Fungi, plants, and animals — like people — are eukaryotes; they are comprised of cells that have actually a plainly specified nucleus. Bacteria, on the other hand, are prokaryotes. They are comprised of cells, which do not have a nucleus and have a various structure, size and residential or commercial properties. The ribosomes of eukaryotic and procaryotic cells, which are accountable for the protein synthesis required for cell development and recreation, are likewise various.

“Some antibiotics, used for treating bacterial infections, work in an interesting way. They bind to the ribosome of bacterial cells and very selectively inhibit protein synthesis. Some proteins are allowed to be made, but others are not,” stated Alexander Mankin, the Alexander Neyfakh Professor of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy at the UIC College of Pharmacy and senior author of the research study. “Without these proteins being made, bacteria die.”

When individuals utilize prescription antibiotics to deal with an infection, the cells of the client are not impacted since the drugs are not developed to bind to the in a different way shaped ribosomes of eukaryotic cells.

“Because there are many human diseases caused by the expression of unwanted proteins — this is common in many types of cancer or neurodegenerative diseases, for example — we wanted to know if it would be possible to use an antibiotic to stop a human cell from making the unwanted proteins, and only the unwanted proteins,” Mankin stated.

To response this concern, Mankin and research study very first author Maxim Svetlov, research study assistant teacher with the department of pharmaceutical sciences, aimed to yeast, a eukaryote with cells comparable to human cells.

Maxim Svetlov, research study assistant teacher with the department of pharmaceutical sciences at the UIC College of Pharmacy. Credit: Svetlov/UIC

The research study group, that included partners from Germany and Switzerland, carried out a “cool trick,” Mankin stated. “We engineered the yeast ribosome to be more bacteria-like.”

Mankin and Svetlov’s group utilized biochemistry and great genes to alter one nucleotide of more than 7,000 in yeast ribosomal RNA, which sufficed to make a macrolide antibiotic — a typical class of prescription antibiotics that works by binding to bacterial ribosomes — act upon the yeast ribosome. Using this yeast design, the scientists used genomic profiling and high-resolution structural analysis to comprehend how every protein in the cell is manufactured and how the macrolide engages with the yeast ribosome.

“Through this analysis, we understood that depending on a protein’s specific genetic signature — the presence of a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ sequence — the macrolide can stop its production on the eukaryotic ribosome or not,” Mankin stated. “This showed us, conceptually, that antibiotics can be used to selectively inhibit protein synthesis in human cells and used to treat human disorders caused by ‘bad’ proteins.”

The experiments of the UIC scientists offer a staging ground for more research studies. “Now that we know the concepts work, we can look for antibiotics that are capable of binding in the unmodified eukaryotic ribosomes and optimize them to inhibit only those proteins that are bad for a human,” Mankin stated.

Reference: “Context-specific action of macrolide antibiotics on the eukaryotic ribosome” by Maxim S. Svetlov, Timm O. Koller, Sezen Meydan, Vaishnavi Shankar, Dorota Klepacki, Norbert Polacek, Nicholas R. Guydosh, Nora Vázquez-Laslop, Daniel N. Wilson and Alexander S. Mankin, 14 May 2021, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-23068-1

Additional co-authors of the research study are Dorota Klepacki and Nora Vázquez-Laslop of UIC; Timm Koller and Daniel Wilson of the University of Hamburg; Sezen Meydan and Nicholas Guydosh of the National Institutes of Health; and Norbert Polacek and Vaishnavi Shankar of the University of Bern.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R35 GM127134, DK075132, 1FI2GM137845), the German Research Foundation (WI3285/6-1), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_166527).