The view from Shukbah Cave. Credit: Amos Frumkin

Long kept in a personal collection, the freshly evaluated tooth of a roughly 9-year-old Neanderthal kid marks the hominin’s southernmost recognized variety. Analysis of the associated historical assemblage recommends Neanderthals utilized Nubian Levallois innovation, formerly believed to be limited to Homo sapiens.

With a high concentration of cavern websites harboring proof of previous populations and their habits, the Levant is a significant center for human origins research study. For over a century, historical excavations in the Levant have actually produced human fossils and stone tool assemblages that expose landscapes lived in by both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, making this area a prospective blending ground in between populations. Distinguishing these populations by stone tool assemblages alone is tough, however one innovation, the unique Nubian Levallois approach, is argued to have actually been produced just by Homo sapiens.

In a brand-new research study released in Scientific Reports, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History partnered with global partners to re-examine the fossil and historical record of Shukbah Cave. Their findings extend the southernmost recognized variety of Neanderthals and recommend that our now-extinct loved ones utilized an innovation formerly argued to be a hallmark of contemporary human beings. This research study marks the very first time the only human tooth from the website has actually been studied in information, in mix with a significant relative research study analyzing the stone tool assemblage.

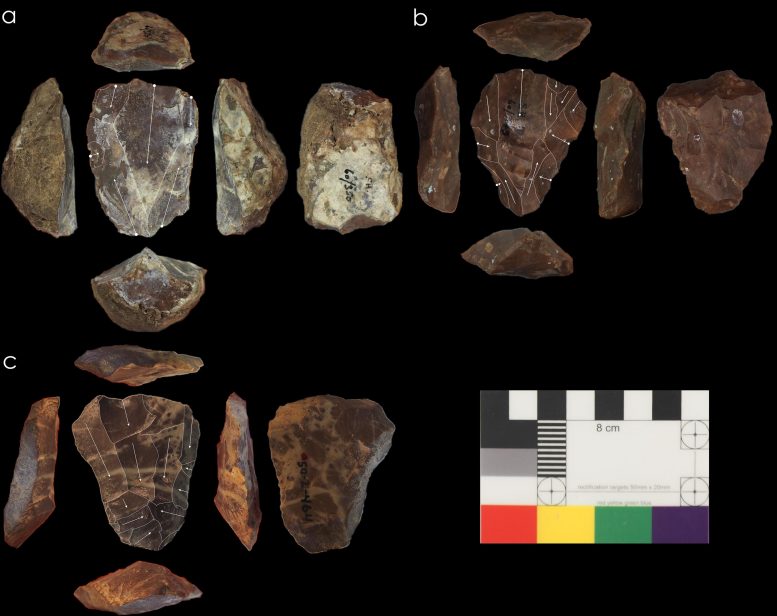

Photos of Nubian Levallois cores related to Neanderthal fossils. Copyright: UCL, Institute of Archaeology & thanks to the Penn Museum, University of Pennsylvania. Credit: Blinkhorn, et al., 2021 / CC BY 4.0

“Sites where hominin fossils are directly associated with stone tool assemblages remain a rarity — but the study of both fossils and tools is critical for understanding hominin occupations of Shukbah Cave and the larger region,” states lead author Dr. Jimbob Blinkhorn, previously of Royal Holloway, University of London and now with the Pan-African Evolution Research Group (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History).

Shukbah Cave was very first excavated in the spring of 1928 by Dorothy Garrod, who reported an abundant assemblage of animal bones and Mousterian-design stone tools sealed in breccia deposits, frequently focused in well-marked hearths. She likewise determined a big, distinct human molar. However, the specimen was kept in a personal collection for the majority of the 20th century, forbiding relative research studies utilizing contemporary techniques. The current re-identification of the tooth at the Natural History Museum in London has actually caused brand-new comprehensive deal with the Shukbah collections.

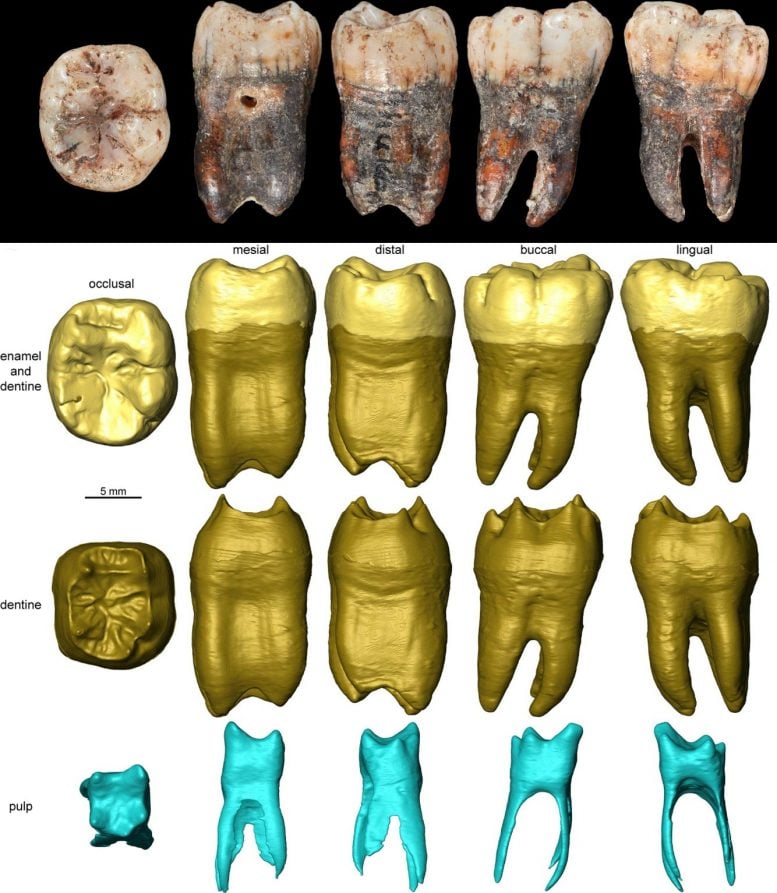

“Professor Garrod immediately saw how distinctive this tooth was. We’ve examined the size, shape, and both the external and internal 3D structure of the tooth, and compared that to Holocene and Pleistocene Homo sapiens and Neanderthal specimens. This has enabled us to clearly characterize the tooth as belonging to an approximately 9-year-old Neanderthal child,” states Dr. Clément Zanolli, from Université de Bordeaux. “Shukbah marks the southernmost extent of the Neanderthal range known to date,” includes Zanolli.

Photo and 3D restoration of a tooth of a 9-year-old Neanderthal kid. Copyright: Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London. Credit: Blinkhorn, et al., 2021 / CC BY 4.0

Although Homo sapiens and Neanderthals shared using a large suite of stone tool innovations, Nubian Levallois innovation has actually just recently been argued to have actually been solely utilized by Homo sapiens. The argument has actually been made especially in southwest Asia, where Nubian Levallois tools have actually been utilized to track human dispersals in the lack of fossils.

“Illustrations of the stone tool collections from Shukbah hinted at the presence of Nubian Levallois technology so we revisited the collections to investigate further. In the end, we identified many more artifacts produced using the Nubian Levallois methods than we had anticipated,” states Blinkhorn. “This is the first time they’ve been found in direct association with Neanderthal fossils, which suggests we can’t make a simple link between this technology and Homo sapiens.”

“Southwest Asia is a dynamic region in terms of hominin demography, behavior, and environmental change, and may be particularly important to examine interactions between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens,” includes Prof Simon Blockley, of Royal Holloway, University of London. “This study highlights the geographic range of Neanderthal populations and their behavioral flexibility, but also issues a timely note of caution that there are no straightforward links between particular hominins and specific stone tool technologies.”

“Up to now we have no direct evidence of a Neanderthal presence in Africa,” stated Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum. “But the southerly location of Shukbah, only about 400 km from Cairo, should remind us that they may have even dispersed into Africa at times.”

Reference: “Nubian Levallois technology associated with southernmost Neanderthals” by James Blinkhorn, Clément Zanolli, Tim Compton, Huw S. Groucutt, Eleanor M. L. Scerri, Lucile Crété, Chris Stringer, Michael D. Petraglia and Simon Blockley, 15 February 2021, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-82257-6

Researchers associated with this research study consist of scholars from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Royal Holloway, University of London, the Université de Bordeaux, the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, the University of Malta, and the Natural History Museum, London. This work was supported by the Leverhulme trust (RPH-2017-087).