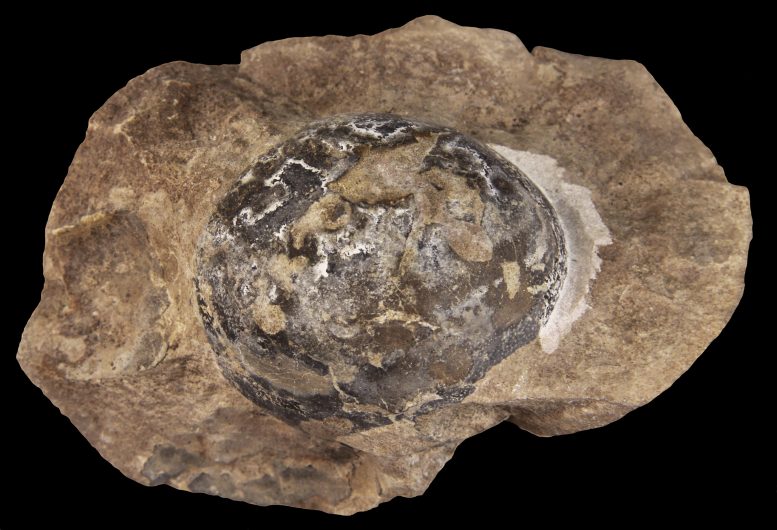

The clutch of fossilized Protoceratops eggs and embryos analyzed in this research study was found in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia at Ukhaa Tolgod. Credit: M. Ellison/©AMNH

New research study recommends that tough eggshells developed a minimum of 3 times in dinosaur ancestral tree.

New research study recommends that the very first dinosaurs laid soft-shelled eggs — a finding that opposes recognized idea. The research study, led by the American Museum of Natural History and Yale University and released on June 17, 2020, in the journal Nature, used a suite of advanced geochemical techniques to examine the eggs of 2 greatly various non-avian dinosaurs and discovered that they looked like those of turtles in their microstructure, structure, and mechanical homes. The research study likewise recommends that hard-shelled eggs developed a minimum of 3 times separately in the dinosaur ancestral tree.

“The assumption has always been that the ancestral dinosaur egg was hard-shelled,” stated lead author Mark Norell, chair and Macaulay Curator in the Museum’s Division of Paleontology. “Over the last 20 years, we’ve found dinosaur eggs around the world. But for the most part, they only represent three groups — theropod dinosaurs, which includes modern birds, advanced hadrosaurs like the duck-bill dinosaurs, and advanced sauropods, the long-necked dinosaurs. At the same time, we’ve found thousands of skeletal remains of ceratopsian dinosaurs, but almost none of their eggs. So why weren’t their eggs preserved? My guess — and what we ended up proving through this study — is that they were soft-shelled.”

The extremely maintained Protoceratops specimen consists of 6 embryos that maintain almost total skeletons. Credit: M. Ellison/©AMNH

Amniotes — the group that consists of birds, mammals, and reptiles — produce eggs with an inner membrane or “amnion” that assists to avoid the embryo from drying. Some amniotes, such as numerous turtles, lizards, and snakes, lay soft-shelled eggs, whereas others, such as birds, lay eggs with tough, greatly calcified shells. The advancement of these calcified eggs, which use increased security versus ecological tension, represents a turning point in the history of the amniotes, as it most likely added to reproductive success therefore the spread and diversity of this group. Soft-shelled eggs hardly ever maintain in the fossil record, that makes it challenging to study the shift from soft to tough shells. Because contemporary crocodilians and birds, which are living dinosaur, lay hard-shelled eggs, this eggshell type has actually been presumed for all non-avian dinosaurs.

The scientists studied embryo-containing fossil eggs coming from 2 types of dinosaur: Protoceratops, a sheep-sized plant-eating dinosaur that resided in what is now Mongolia in between about 75 and 71 million years earlier, and Mussaurus, a long-necked, plant-eating dinosaur that grew to 20 feet in length and lived in between 227 and 208.5 million years earlier in what is now Argentina. The extremely maintained Protoceratops specimen consists of a clutch of a minimum of 12 eggs and embryos, 6 of which maintain almost total skeletons. Associated with the majority of these embryos — which have their foundations and limbs bent — constant with the position the animals would presume while growing within the egg — is a scattered black-and-white egg-shaped halo that obscures a few of the skeleton.

In contrast, 2 possibly hatched Protoceratops babies in the specimen are mostly without the mineral halos. When they took a better take a look at these halos with a petrographic microscopic lense and chemically defined the egg samples with high-resolution in situ Raman microspectroscopy, the scientists discovered chemically modified residues of the proteinaceous eggshell membrane that comprises the innermost eggshell layer of all contemporary archosaur eggshells. The very same held true for the Mussaurus specimen. And when they compared the molecular biomineralization signature of the dinosaur eggs with eggshell information from other animals, consisting of lizards, crocodiles, birds, and turtles, they figured out that the Protoceratops and Mussaurus eggs were certainly non-biomineralized — and, for that reason, leatherlike and soft.

This fossilized egg was laid by Mussaurus, a long-necked, plant-eating dinosaur that grew to 20 feet in length and lived in between 227 and 208.5 million years earlier in what is now Argentina. Credit: © D. Pol

“It’s an exceptional claim, so we need exceptional data,” stated research study author and Yale college student Jasmina Wiemann. “We had to come up with a brand-new proxy to be sure that what we were seeing was how the eggs were in life, and not just a result of some strange fossilization effect. We now have a new method that can be applied to all other sorts of questions, as well as unambiguous evidence that complements the morphological and histological case for soft-shelled eggs in these animals.”

With information on the chemical structure and mechanical homes of eggshells from 112 other extinct and living loved ones, the scientists then built a “supertree” to track the advancement of the eggshell structure and homes through time, discovering that hard-shelled, calcified eggs developed separately a minimum of 3 times in dinosaurs, and most likely established from an ancestrally soft-shelled type.

“From an evolutionary perspective, this makes much more sense than previous hypotheses, since we’ve known for a while that the ancestral egg of all amniotes was soft,” stated research study author and Yale college student Matteo Fabbri. “From our study, we can also now say that the earliest archosaurs — the group that includes dinosaurs, crocodiles, and pterosaurs — had soft eggs. Up to this point, people just got stuck using the extant archosaurs — crocodiles and birds — to understand dinosaurs.”

Because soft eggshells are more conscious water loss and deal little security versus mechanical stress factors, such as a brooding moms and dad, the scientists propose that they were most likely buried in damp soil or sand and after that nurtured with heat from breaking down plant matter, comparable to some reptile eggs today.

###

Reference: “The first dinosaur egg was soft” by Mark A. Norell, Jasmina Wiemann, Matteo Fabbri, Congyu Yu, Claudia A. Marsicano, Anita Moore-Nall, David J. Varricchio, Diego Pol and Darla K. Zelenitsky, 17 June 2020, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2412-8

Other authors on this paper consist of Congyu Yu from the American Museum of Natural History; Claudia Marsicano from the University of Buenos Aires; Anita Moore-Nall and David Varricchio from Montana State University; Diego Pol from the Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio, Argentina; and Darla K. Zelenitsky from the University of Calgary.