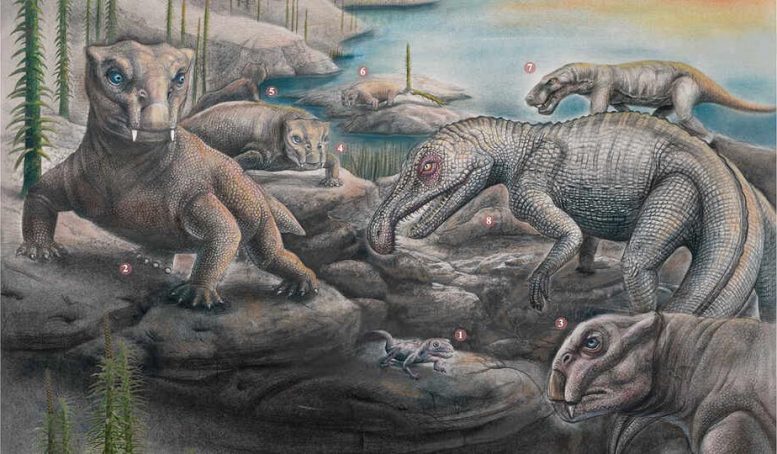

The plant-eating pareiasaurs were taken advantage of by sabre-toothed gorgonopsians. Both groups passed away out throughout completion-Permian mass termination, or “The Great Dying.” Credit: © Xiaochong Guo

By identifying how ancient life reacted to ecological stress factors, scientists get insights into how contemporary types may fare.

Over the course of Earth’s history, a number of mass termination occasions have actually damaged communities, consisting of one that notoriously eliminated the dinosaurs. But none were as ravaging as “The Great Dying,” which occurred 252 million years earlier throughout completion of the Permian duration. A brand-new research study, released on March 17, 2021, in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, displays in information how life recuperated in contrast to 2 smaller sized termination occasions. The worldwide research study group—made up of scientists from the China University of Geosciences, the California Academy of Sciences, the University of Bristol, Missouri University of Science and Technology, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences—revealed for the very first time that completion-Permian mass termination was harsher than other occasions due to a significant collapse in variety.

After the mass termination, the environment was uncommon, with extremely typical examples of the dicynodont Lystrosaurus, in some cases consisting of 90% of the assemblage. Credit: © Xiaochong Guo

To much better identify “The Great Dying,” the group looked for to comprehend why neighborhoods didn’t recuperate as rapidly as other mass terminations. The primary factor was that completion-Permian crisis was a lot more extreme than any other mass termination, erasing 19 out of every 20 types. With survival of just 5% of types, communities had actually been damaged, and this indicated that environmental neighborhoods needed to reassemble from scratch.

To examine, lead author and Academy scientist Yuangeng Huang, now at the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, rebuilded food webs for a series of 14 life assemblages covering the Permian and Triassic durations. These assemblages, tested from north China, used a picture of how a single area on Earth reacted to the crises. “By studying the fossils and evidence from their teeth, stomach contents, and excrement, I was able to identify who ate whom,” states Huang. “It’s important to build an accurate food web if we want to understand these ancient ecosystems.”

By completion of the Permian, pareiasaurs had actually ended up being big and armored for self-protection. Other plant-eaters consisted of dicynodonts, taken advantage of by dinocephalians . This complex environment collapsed throughout completion-Permian mass termination occasion, and just a few dicynodonts endured. Credit: © Xiaochong Guo

The food webs are comprised of plants, mollusks, and bugs residing in ponds and rivers, in addition to the fishes, amphibians, and reptiles that consume them. The reptiles vary in size from that of contemporary lizards to half-ton herbivores with small heads, enormous barrel-like bodies, and a protective covering of thick bony scales. Sabre-toothed gorgonopsians likewise strolled, some as big and effective as lions and with long canine teeth for piercing thick skins. When these animals passed away out throughout completion-Permian mass termination, absolutely nothing took their location, leaving out of balance communities for 10 million years. Then, the very first dinosaurs and mammals started to progress in the Triassic. The very first dinosaurs were little—bipedal insect-eaters about one meter long—however they quickly ended up being bigger and diversified as flesh- and plant-eaters.

“Yuangeng Huang spent a year in my lab,” states Peter Roopnarine, Academy Curator of Geology. “He applied ecological modeling methods that allow us to look at ancient food webs and determine how stable or unstable they are. Essentially, the model disrupts the food web, knocking out species and testing for overall stability.”

“We found that the end-Permian event was exceptional in two ways,” states Professor Mike Benton from the University of Bristol. “First, the collapse in diversity was much more severe, whereas in the other two mass extinctions there had been low-stability ecosystems before the final collapse. And second, it took a very long time for ecosystems to recover, maybe 10 million years or more, whereas recovery was rapid after the other two crises.”

Ultimately, identifying neighborhoods—particularly those that recuperated effectively—offers important insights into how contemporary types may fare as people press the world to the verge.

“This is an amazing new result,” states Professor Zhong-Qiang Chen of the China University of Geosciences, Wuhan. “Until now, we could describe the food webs, but we couldn’t test their stability. The combination of great new data from long rock sections in north China with cutting-edge computational methods allows us to get inside these ancient examples in the same way we can study food webs in the modern world.”

Reference: “Ecological dynamics of terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems across three mid-Phanerozoic mass extinctions from northwest China” by Yuangeng Huang, Zhong-Qiang Chen, Peter D. Roopnarine, Michael J. Benton, Wan Yang, Jun Liu, Laishi Zhao, Zhenhua Li and Zhen Guo, 17 March 2021, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0148