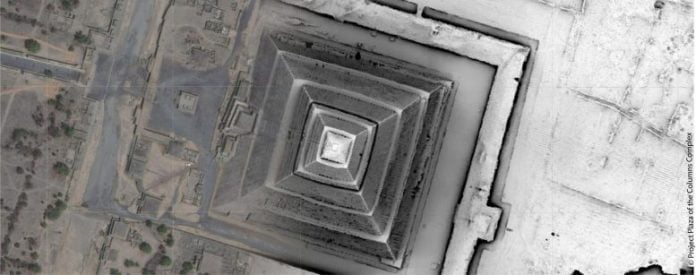

A lidar and satellite picture of the Sun Pyramid atTeotihuacan The satellite part is on the left half of the image and the lidar part, which reveals buried walls and other historical functions, is on the right. Credit: Nawa Sugiyama

Lidar mapping research study exposes huge landscape adjustments that still affect building and farming.

A lidar mapping research study utilizing an innovative aerial mapping innovation reveals ancient locals of Teotihuacan moved impressive amounts of soil and bedrock for building and improved the landscape in such a way that continues to affect the shapes of contemporary activities in this part ofMexico The work is released in the open-access journal, PLOS One

The paper likewise demonstrates how Teotihuacan’s engineers re-routed 2 rivers to line up with points of huge significance, recognized numerous formerly unidentified architectural functions, and recorded over 200 historical functions that have actually been ruined by mining and urbanization because the 1960 s.

“We don’t live in the past, but we live with the legacies of past actions. In a monumental city like Teotihuacan, the consequences of those actions are still fresh on the landscape,” stated very first author Nawa Sugiyama, a teacher of sociology at UC Riverside.

Teotihuacan, about 25 miles northeast of contemporary Mexico City, was the biggest city in the Americas and among the biggest throughout the ancient world. It existed from about 100 BCE-550 CE– about 1,000 -2,000 years back– and covered 8 square miles. At its height, it included various pyramids, plazas, and properly designed domestic and business communities real estate a population of around 100,000 Some of the pyramids and other structures show up above ground today, however the majority of the city’s remains lie buried below contemporary fields, structures, and other activity locations.

To map the below-ground parts of Teotihuacan, Nawa Sugiyama and co-authors Saburo Sugiyama at Arizona State University; Tanya Catignani at George Mason University; Adrian S. Z. Chase at Claremont University; and Juan C. Fernandez-Diaz at Houston University utilized lidar, a mapping innovation that determines the quantity of time it takes light from a laser to recuperate from a things. Archaeologists typically utilize lidar to find buried functions covered by thick forests or open fields however seldom release the innovation where historical remains lie below metropolitan locations.

“Lidar is often perceived as revolutionary tool to find ancient features hidden in plain sight, but we found the lidar map to be extremely messy and hard to interpret. Many of the features we identified were modern with ancient roots. But then we realized there is a far more interesting story behind this trend,” stated NawaSugiyama

Because the large scale of building at Teotihuacan recommended huge adjustment of the ancient landscape, Sugiyama’s group believed that lidar might assist illuminate the relationship in between the design of Teotihuacan and contemporary activities that overlay it. The scientists verified the lidar findings with studies by foot and contrasts to previous mapping efforts.

They discovered that the home builders of Teotihuacan leveled the ground to the bedrock and, sometimes, quarried the bedrock itself to utilize as building and fill product. In simply one part of the city, called the Plaza of the Columns Complex, the authors computed that approximately 372,056 square meters of synthetic ground built up throughout approximately 300 years of building that had actually been quarried in other places in the TeotihuacanValley In 3 of the primary pyramid complexes, the authors approximate that 2,423,411 square meters of rock, dirt, and adobe had actually been utilized.

This significant improving of the landscape impacts the plan of contemporary building and activities. The authors discovered that 65% of metropolitan locations included home or contemporary functions that lined up orthogonally within 3 degrees of 15 degrees east of huge north– the very same positioning asTeotihuacan Rock fences were constructed along locations that lidar and excavation exposed to have underground ancient walls that made modern-day raking challenging.

Teotihuacan engineers likewise rerouted the Rio San Juan and the San Lorenzo River, which cross the city. Rio San Juan follows the Teotihuacan orientation for 3 km as it passes through the town hall while the San Lorenzo River has an extremely unique orientation, 8 degrees south of huge east for 4.9 km. Previous research study has actually translated them as significant canals of symbolic and calendric significance.

The lidar map likewise revealed that other areas of canals and rivers, lots of still actively utilized today, were modified at numerous points along its course, often accompanying the Teotihuacan directionalities. An overall of 16.9 km of the hydrological systems noticeable on the contemporary surface had origins in the Early Classic Teotihuacan landscape.

On the lidar map, the group recognized 298 functions and 5,795 human-made balconies that had actually not been formerly tape-recorded. However, they likewise recognized over 200 recognized functions that have actually been ruined by mining because2015

“We can’t fight modern urbanization. The lidar map provides a snapshot of these ancient features that are being abolished at an alarming rate that would otherwise go unnoticed. It’s one of many ways we can preserve our heritage landscape,” stated Nawa Sugiyama.

The authors prepare to utilize their lidar map to develop a three-dimensional geospatial database that permits them to picture stratigraphic and surface area information, natural and synthetic functions, and to record the real degree of people as geomorphic representatives over extended periods of time in the TeotihuacanValley

Reference: “Humans as geomorphic agents: Lidar detection of the past, present and future of the Teotihuacan Valley, Mexico” by Nawa Sugiyama, Saburo Sugiyama, Tanya Catignani, Adrian S. Z. Chase and Juan C. Fernandez-Diaz, 20 September 2021, PLOS One

DOI: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0257550