Long misconstrued, snake tongues have actually captivated biologists for centuries.

As dinosaurs lumbered through the damp cycad forests of ancient South America 180 million years earlier, primeval lizards scooted, undetected, underneath their feet. Perhaps to prevent being squashed by their huge kin, a few of these early lizards looked for haven underground.

Here they progressed long, slim bodies and minimized limbs to work out the narrow nooks and crevices underneath the surface area. Without light, their vision faded, however to take its location, a particularly intense sense of odor progressed.

It was throughout this duration that these proto-snakes progressed among their most renowned qualities – a long, flicking, forked tongue. These reptiles ultimately went back to the surface area, however it wasn’t up until the termination of dinosaurs numerous countless years later on that they diversified into myriad kinds of modern-day snakes.

As an evolutionary biologist, I am captivated by these unusual tongues – and the function they have actually played in snakes’ success.

A puzzle for the ages

Snake tongues are so strange they have actually captivated biologists for centuries. Aristotle thought the forked pointers offered snakes a “twofold pleasure” from taste – a view mirrored centuries later on by French biologist Bernard Germain de Lacépède, who recommended the twin pointers might adhere more carefully to “the tasty body” of the future treat.

A 17th-century astronomer and biologist, Giovanni Battista Hodierna, believed snakes utilized their tongues for “picking the dirt out of their noses … since they are always grovelling on the ground.” Others competed the tongue caught flies “with wonderful nimbleness … betwixt the forks,” or collected air for nourishment.

One of the most consistent beliefs has actually been that the darting tongue is a poisonous stinger, a mistaken belief perpetuated by Shakespeare with his numerous referrals to “stinging” snakes and adders, “Whose double tongue may with mortal touch throw death upon thy … enemies.”

According to the French biologist and early evolutionist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, snakes’ minimal vision required them to utilize their forked tongues “to feel several objects at once.” Lamarck’s belief that the tongue operated as an organ of touch was the dominating clinical view by the end of the 19th century.

Smelling with tongues

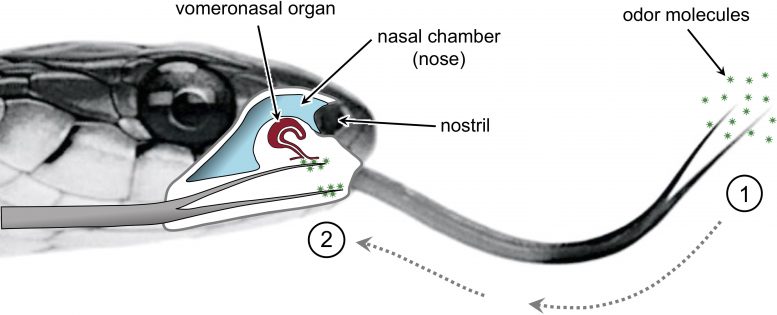

Clues to the real significance of snake tongues started to emerge in the early 1900s when researchers turned their attention to 2 bulblike organs situated simply above the snake’s taste buds, listed below its nose. Known as Jacobson’s, or vomeronasal, organs, each opens to the mouth through a small hole in the taste buds. Vomeronasal organs are discovered in a range of land animals, consisting of mammals, however not in a lot of primates, so human beings don’t experience whatever feeling they offer.

Tongue pointers provide smell particles to the vomeronasal organ. Credit: Kurt Schwenk, CC BY-ND

Scientists discovered that vomeronasal organs are, in reality, a spin-off of the nose, lined with comparable sensory cells that send out impulses to the exact same part of the brain as the nose, and found that small particles got by the tongue pointers wound up inside the vomeronasal organ. These advancements caused the awareness that snakes utilize their tongues to gather and carry particles to their vomeronasal organs – not to taste them, however to smell them.

Sampling 2 points at the same time. Credit: Kurt Schwenk

In 1994, I utilized movie and image proof to reveal that when snakes sample chemicals on the ground, they separate their tongues pointers far apart simply as they touch the ground. This action enables them to sample smell particles from 2 commonly apart points concurrently.

Each idea provides to its own vomeronasal organ independently, enabling the snake’s brain to evaluate immediately which side has the more powerful odor. Snakes have 2 tongue pointers for the exact same factor you have 2 ears – it supplies them with directional or “stereo” odor with every flick – an ability that ends up being exceptionally beneficial when following scent routes left by prospective victim or mates.

Fork-tongued lizards, the legged cousins of snakes, do something really comparable. But snakes take it one action further.

Swirls of smell

Unlike lizards, when snakes gather smell particles in the air to odor, they oscillate their forked tongues up and down in a blur of fast movement. To imagine how this impacts air motion, college student Bill Ryerson and I utilized a laser focused into a thin sheet of light to light up small particles suspended in the air.

We found that the flickering snake tongue produces 2 sets of little, swirling masses of air, or vortices, that imitate small fans, pulling smells in from each side and jetting them straight into the course of each tongue idea.

Tongue-flicking develops little eddies in the air, condensing the particles drifting within it. Credit: Kurt Schwenk, CC BY-ND

Since smell particles in the air are scarce, our company believe snakes’ special type of tongue-flicking serves to focus the particles and accelerate their collection onto the tongue pointers. Preliminary information likewise recommends that the air flow on each side stays different enough for snakes to take advantage of the exact same “stereo” odor they obtain from smells on the ground.

Owing to history, genes and other aspects, natural choice typically falls brief in developing efficiently developed animal parts. But when it concerns the snake tongue, advancement appears to have actually struck one out of the park. I question any engineer might do much better.

Written by Kurt Schwenk, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut.

Originally released on The Conversation.![]()

![]()